Former newspaper reporters move into brand journalism.

As a former web editor for The Columbian, Libby Clark edited news sites, developed content strategies and targeted readers. Clark now performs similar tasks for the Linux Foundation, which uses news blogs to build community and foster discussion about the operating system. “I’m writing articles and editing them for the web,” says Clark. “I have almost entirely full editorial control. So I’m writing like a journalist would.”

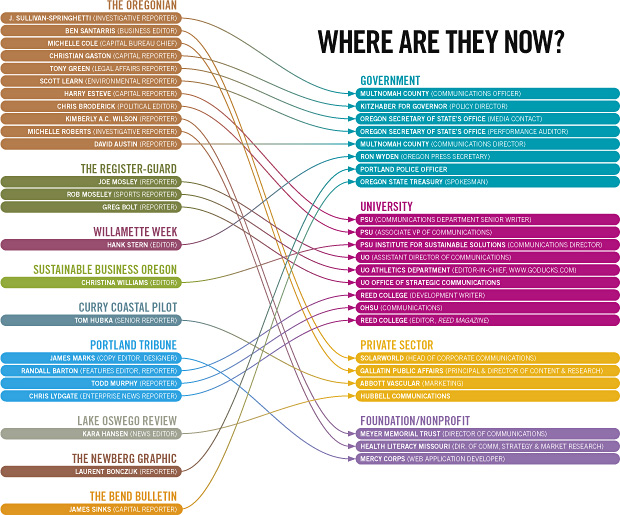

Clark is part of what might be termed the great journalism migration. As the newspaper industry shrinks, triggering mass layoffs, buyouts and elective departures, more reporters are moving into “brand journalism”: news content paid for by companies and distributed via their own media channels. The skill sets are similar, and in many cases, brand journalism offers better compensation and job security.

There has always been an escape hatch leading from journalism into public relations and marketing. But as organizations of all stripes fill the vacuum created by the decline of the traditional news media, that route is taken more frequently. Today, all companies and organizations — makers of consumer products, food and hospitality industries, health care, universities, government agencies — are becoming media companies. And they’re hiring brand journalists to serve as storytellers for their brands.

Brand journalism allows businesses, nonprofits and government agencies to connect directly with readers — while offering gainful employment to legions of ex-reporters. But the rise of brand journalism also raises red flags about the loss of the journalist and the independent, critical viewpoint.

Hannah Hoffman, president of the Society of Professional Journalists’ Oregon and Southwest Washington Chapter, frames the problem facing the journalist turned brand journalist within the context of the Cover Oregon debacle.

“How weird would it be to have one of these [marketing] jobs and be doing it for Oracle right now?” she asks. “That would be uncomfortable.” A reporter covering an organization from the outside reports on challenges as diligently as successes, Hoffman says. “There’s a sense that there’s kind of a pure purpose at heart there; you’re trying to get to the truth of what’s happening in this world.” This isn’t the case with brand journalism, whose purpose it is to build, well, a brand.

But for many journalists, the transition to communications is natural — and seamless. “The economy is largely a war for attention now,” says Marshall Kirkpatrick, a former tech reporter whose development of web-based news breaking systems led him to start the social intelligence software company LittleBird.

As the traditions news business model has collapsed, there has been a corresponding explosion in niche-media products, Kirkpatrick says. “It’s so easy to speak that it’s a challenge to be heard. So a professional skill set that comes from being a practiced, experienced communicator on the web, and a familiarity with the lay of the land, is a unique and valuable thing.”

Better compensation and an opportunity to work in a growth industry were among the draws for Nathan Isaacs, who left a job at the Tri-City Herald in 2007 and now works as a marketing manager for OpConnect, a maker of EV charging systems.

After getting an MBA, Isaacs nearly doubled his salary moving from journalism to tech. “You go to a clean tech or EV conference and it’s like: How will we not take over the world?” Isaacs says. That optimism comes as a relief after years working in a declining (journalism) industry, he says.

According to a Pew Research Center analysis released in August, the number of reporters nationwide decreased from 52,550 in 2004 to 43,630 in 2013, a 17% loss. In contrast, the number of public relations specialists during this time frame grew by 22%, from 166,210 to 202,530. The pay differential between journalists and public relations specialists has also widened. In 2013, marketing specialists earned a median annual income of $54,940 compared with $35,600 for reporters.

The Oregon Newspaper Publishers Association does not track layoffs, buyouts or circulation. According to Colby Reade, board member of the Oregon Chapter of the Public Relations Society of America, the chapter is seeing its highest membership numbers in recent years.

Like Isaacs and Clark, many journalists who have moved into marketing say their new positions allow them to utilize their reporting and writing skills while putting them on the front lines of modern-day communications.

But if former reporters find communications jobs rewarding and meaningful, they are also keenly aware of the difference between brand journalism and the journalism they produced in their former careers as journalists.

Aliza Earnshaw, a former reporter for the Portland Business Journal, now works on the marketing team at the Portland software company Puppet Labs. Her job includes writing e-books about industry happenings, like one about continuous delivery.

But those e-books are designed to generate sales leads — people who download the e-books log in. And at least in a business environment, brand journalism has always had as its end goal the bottom line of the company producing it, Earnshaw says.

As the traditional journalism model disappears, “[companies] might feel they have to do a little more, perhaps educational content or something,” says Earnshaw. “But a profit-making entity that has owners to answer to, whether they are public or private, and has people whose livings depend on it is not going to spend a lot of time or energy or money on something that doesn’t directly serve its business.”

As for profit businesses, newspapers are not immune to these pressures. Journalists have historically considered their profession — holding government and corporations accountable — to be a “noble calling.” But declining revenues and staff in the newspaper business have made it difficult, if not impossible, to sustain that ideal.

In-depth reporting that was once a staple of daily newspapers is also more expensive harder to produce. Plus, news organizations are now pressed to brand themselves as aggressively as the competition, with traffic-based compensation models now being adopted by many digital news operations.

In this climate, many reporters harbor mixed feelings about the changing media environment: nostalgia for the good old days, appreciation for their current job and concerns about the quality of news in the digital age.

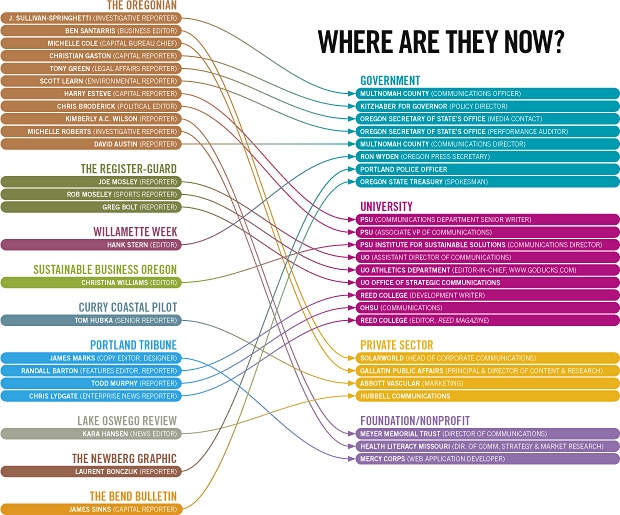

“Journalism was changing and I was changing,” says Julie Sullivan-Springhetti, a former investigative reporter for The Oregonian who now works as a communications officer for the Multnomah County Health Department. “I didn’t know where I was going to meet my challenges, my personal development, in a constricting industry.”

Working in government relations on behalf of vulnerable populations is part of a natural career evolution, Sullivan-Springhetti says. But as a reader, she adds, she still looks to journalists for objective reporting.

“There’s a gap, and I think organizations are rightly stepping in because they are trying to reach an audience. To the extent that we’ve created ways to reach our audience … I would never believe that any of us could replace the essential role of a journalist. We just can’t.”

The inevitable horrors of working in a collapsing industry have hit journalism hard: layoffs, pay cuts, the constant shuffling and reshuffling of duties, contracting benefits, lack of access to professional growth opportunities, and a sense that one has hit the skids. For now, brand journalism has stepped in to fill some of the void.

But the great migration is more than a workforce shift. Corporations, nonprofits and government agencies are advancing into the world of content, and more and more reporters are moving out of journalism and into public relations.

An open question is what news agencies will be left to report on those organizations, and whether media companies can reinvent themselves in time to salvage the heart and soul of the fourth estate: news in the public interest.