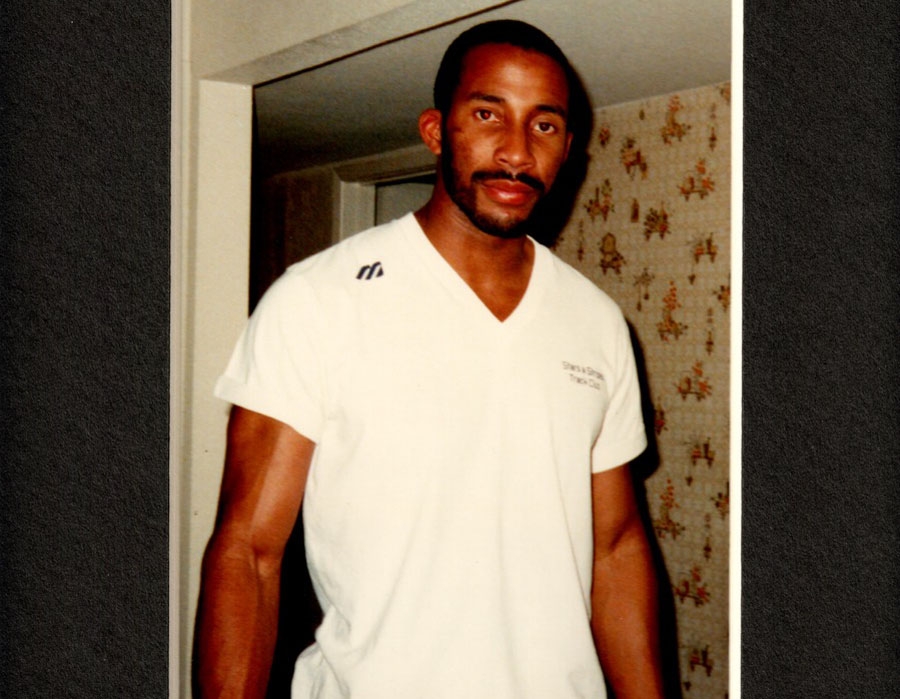

Charles Wilhoite reflects on several decades of civic leadership and a Portland tenure bookended by racial violence.

“What on earth does a financial expert do for the world?”

My wonderful mother asked me this question nearly 30 years ago when I told her I was leaving my position as an auditor with KPMG to join my current firm, Willamette Management Associates.

My ever-present beacon of a father simply smiled in the background — one of the many valuable “hints” he imparted to me over the years to ensure a happy marriage!

It was a fair question. My parents were lifelong educators — my mother a teacher and my father a principal — each with over 25 years of dedicated, impactful service to boarding schools operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs on the Navajo Reservation in northern Arizona.

Both clearly understood that, as a public accountant, I was part of a body of accounting professionals that provides independent assurances to the public regarding the completeness and accuracy of financial information.

The thought of my making a living by providing my opinion, for a fee, regarding what I think something is worth was a foreign concept to them, and sounded much less secure than my life as an auditor.

I tried to be as succinct as possible in my explanation.

Nearly 30 years later, however, they still both, conveniently and comfortably, sum up my professional career with the rhetorical question, “You work with numbers, right?”

Yes, I work with numbers. And while I have enjoyed my professional career immensely, I have appreciated even more the wonderful opportunities to contribute to society that my career path has afforded me.

One of six children growing up in the small, rural town of Winslow, Arizona, I witnessed firsthand many of the ravages of various forms of abuse and homelessness, and the enduring impacts of inadequate education.

Without realizing it at the time, I was being programmed — both by my servant-leader parents and the circumstances surrounding me — to pursue a life of positive change.

As I reflect on my professional and personal development, I can’t help but smile, even laugh at myself, as I recount the number of times people have sincerely questioned my apparent inability to “just say no.”

At the ripe old age of 53, I am both proud and a bit concerned to admit that I have served on 17 boards of directors, and numerous other commissions and committees. Such service includes my current role as chair of the Meyer Memorial Trust, which operates with the deeply satisfying, singular mission of creating a flourishing and equitable Oregon.

For those who know me, I truly believe that they understand I have never sought attention or distinction through service. Similarly, I have never pursued roles for the primary purpose of advancing myself professionally, or for economic gain.

The simple truth is, as a financially-savvy African-American male firmly rooted in the captivating, but very white, Pacific Northwest, I consider it a responsibility to always make an effort to accept a role when it affords me the opportunity to impact the region.

The appreciation of my personal circumstances creates an obligation to do what I can to make life better for others—particularly people of color and the marginalized.

As I look at our world today, and at Oregon, I find myself disheartened, confused, and yes, angry. I have a wonderful, white wife who has given me the priceless gift of three intelligent, beautiful, and considerate mixed-race children who are becoming fine adults.

Yet every day I leave my home and find myself navigating communities that, surprisingly, seem to become more divided, and a society that, unfortunately, seems to be developing more keen abilities at compartmentalizing and rationalizing the unacceptable.

It should be unacceptable to everyone that two individuals died and another was gravely injured on one of our MAX trains last month because they chose to defend the unalienable civil rights of two teenage minority girls under racist attack.

Similarly, it should be unacceptable to everyone that high school drop-out rates, unemployment rates, and rates of homelessness and health disparity are double-digit percentage points higher for communities of color and the poor.

There is significant, tragic irony in the fact that I moved to Portland in 1990, smack-dab in the middle of the racial ugliness associated with the Tom Metzger trial.

That ugliness includes memories of individuals spewing the N-word at me as they sped by in cars during my walks to work.

Fortunately for me they were in cars, because I fear I would have reacted very differently at my young age had they been on foot, with potentially dire consequences.

After the court ruled against him, concluding that he was responsible for the racially motivated murder of Mulugeta Seraw, Metzger eerily stated,

“The movement will not be stopped in the puny town of Portland. We’re too deep. We’re embedded now … Stopping Tom Metzger is not going to change what’s going to happen to this country.”

The very appreciation of life obligates each of us to always stand against intolerance and injustice whenever and wherever they rear their ugly heads.

Discrimination of any type is unacceptable, because if you condone it, you own it, and by doing so, you perpetuate it. The goal is to prove Metzger wrong.

With this thought in mind, I gladly accept the reality that I will continue to have difficulty saying no.

Charles Wilhoite is a managing director at Willamette Management Associates.