As Oregon wrestles with change from old industrial models to new, the state’s education system is re-engineering how it produces talent for the state’s employers.

That means systemic shift, away from an assembly-line approach to one that recognizes the greater complexity of an extended relationship between administrators, teachers and students.

For the past 13 years, Chalkboard Project has helped guide that conversation. Born in 2003 out of an alliance among six of Oregon’s major foundations, Chalkboard Project became the public face of a new nonprofit called Foundations for a Better Oregon.

Its focus? Fostering a discussion and supporting efforts to improve education in Oregon’s K-12 schools.

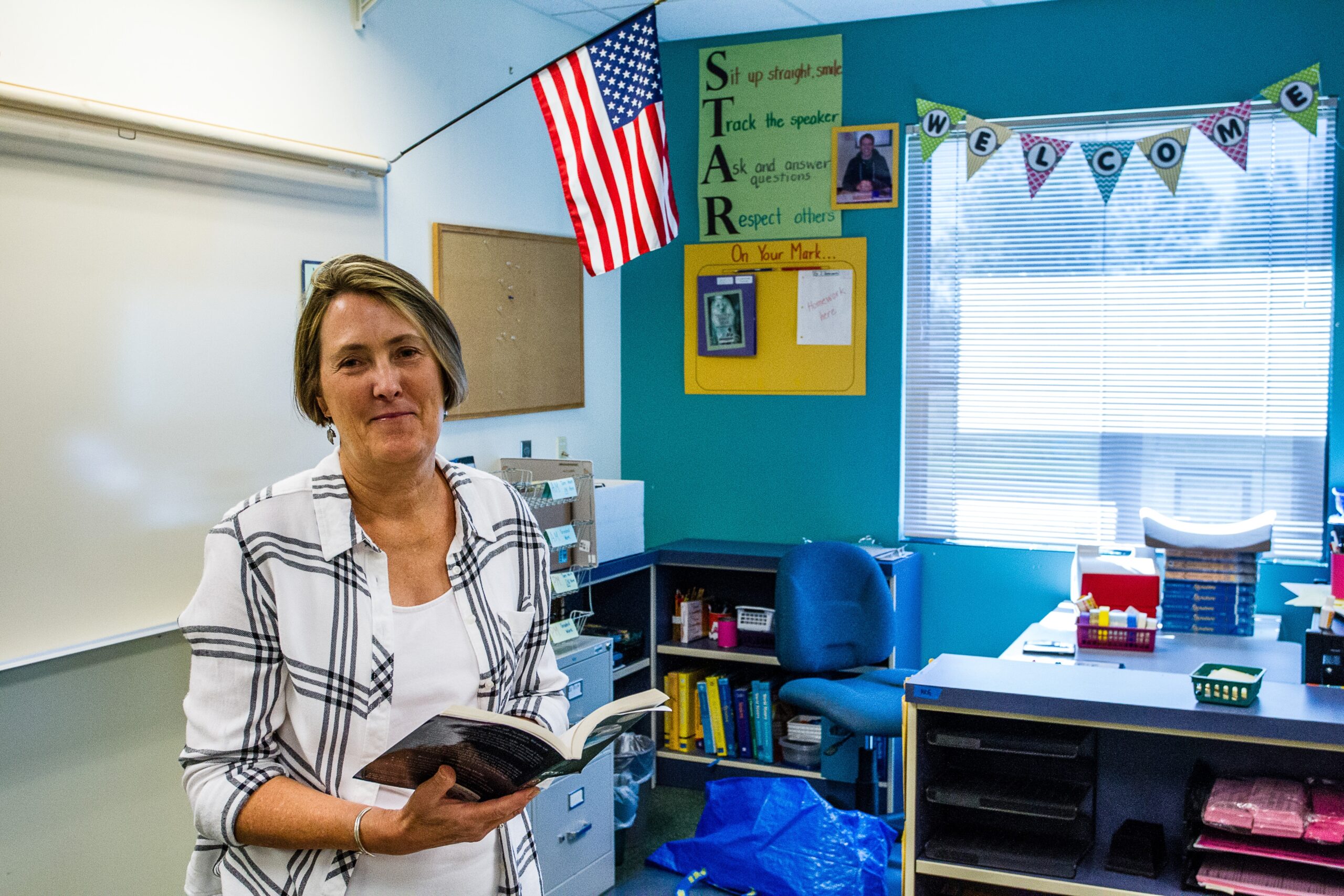

Sue Dickman, a recently retired sixth-grade teacher from Springfield, applauds her district’s embrace of initiatives that sprung out of Chalkboard Project.

“I’m proud of what the district has done,” Dickman says. “It’s been a result of funding from TeachOregon.”

TeachOregon is one of three Chalkboard initiatives focused on creating and supporting classroom teachers.

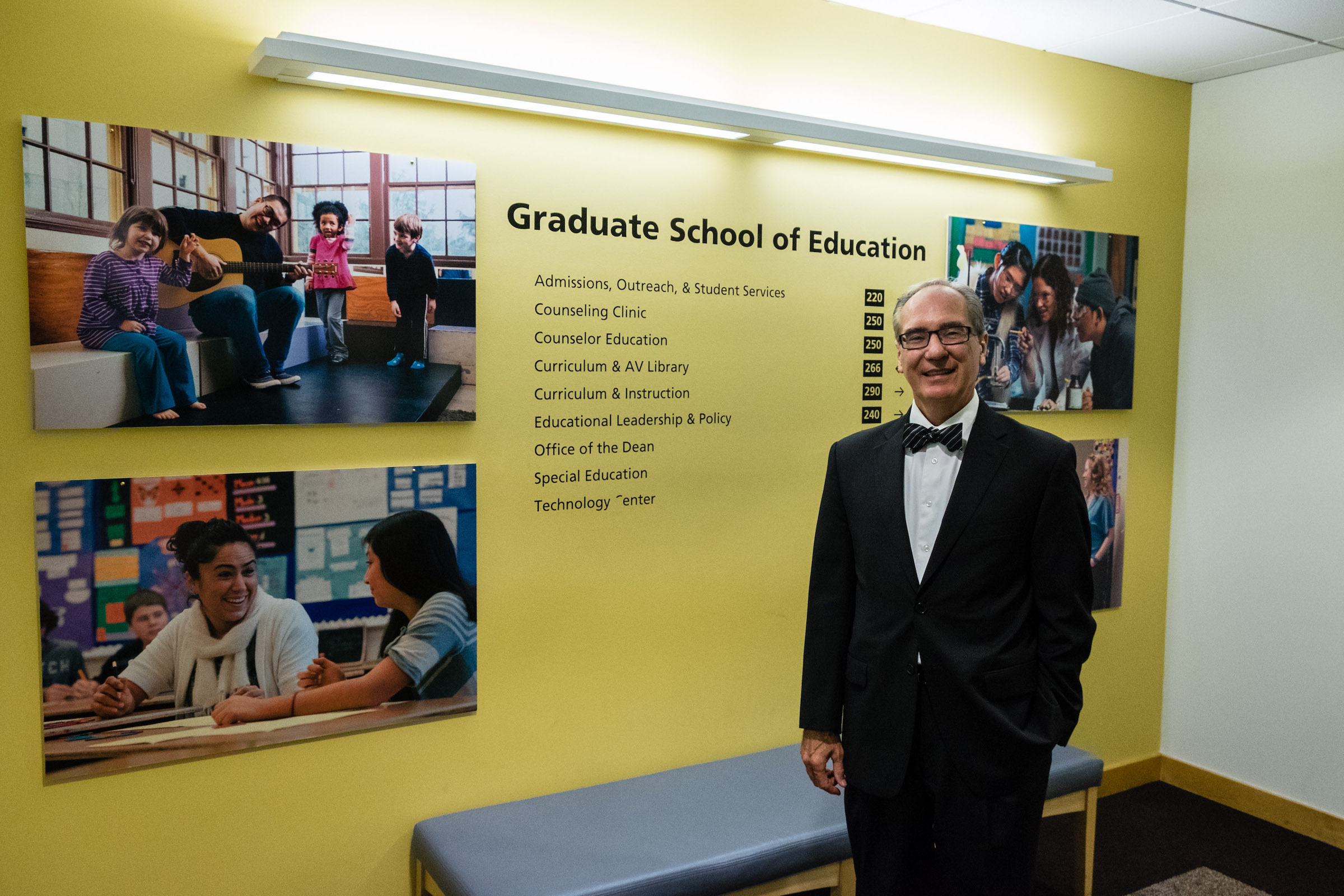

“TeachOregon is trying to create a seamless system of professional preparation and ongoing professional development for teachers,” says Randy Hitz, dean of the graduate school of education at Portland State University.

Randy Hitz, dean of the graduate school of education at Portland State University

“At the heart of that is creating a better clinical experience for training teachers.”

In this sense, clinical means that period when student teachers first enter the classroom and begin working with kids. Thirty years ago, when Dickman started out, these “teacher candidates” got one term of practical time with students.

“And the cooperating teacher stepped away and let the student teacher sink or swim,” Dickman says.

That was a failure, she says, in several ways. As the host teacher, she wasn’t comfortable turning her class over to a rookie. “Those kids were my responsibility,” Dickman says.

Hitz says Portland State, like other schools, now trains teachers in a fifth-year cohort, after they focus their undergrad studies on the material they want to teach. Teacher candidates work with veteran teachers in the classroom during the entire fifth year of study, gradually taking on more responsibility.

“Experienced teachers need to help raise new teachers,” Dickman says. “If we want good teaching, then we have to step forward and train.”

Her district embraced a model out of Minnesota, in which experienced teachers stay in the classroom and work closely with candidate teachers. Data showed greater student progress in such “co-teaching” situations.

Hitz says most Oregon teacher training programs have embraced that model.

“It’s more of a mentoring relationship,” he says. “You don’t want to replace a master teacher with a novice. It’s not fair to the students.”

For three years, Dickman was among more than 400 Oregon “co-teachers.” She says it’s too early to say if it has helped slow Oregon’s 33 percent four-year teacher burnout rate.

“Anecdotally, young teachers say they feel better prepared,” Dickman says.

Hitz says TeachOregon is hoping to bolster the pipeline that leads young people into teaching.

“One of the first things the school districts said to us was, ‘Can we help you recruit people into the field? We want good people, and we want a diverse population of teachers’,” he recalls.

As a result of that feedback, TeachOregon has helped engage nearly 150 middle school students in Pro Team programs to explore teaching as a profession. Another 462 high school students continue looking at teaching careers as Teacher Cadets or Aspiring Teachers. And well over 100 community college students are on Teaching Pathway programs.

Chalkboard’s first initiative aimed squarely at existing teachers. Known as CLASS (Creative Leadership Achieves Student Success), it vaulted in 2011 to formal funding support inside the Oregon Department of Education.

The 2015 Legislature appropriated $16 million to fund district-driven plans that address four key goals: broaden career paths for teachers, refine teacher evaluation, expand professional development opportunities, and expand compensation models.

“We could not have had the collaboration that we did in our district without the support of Chalkboard,” says Allan Bruner, a 2006 Oregon Teacher of the Year and a 27-year teacher of science at Colton High School in Clackamas County.

He began working with Chalkboard four years ago, when Sue Hildick, its president, convened a 15-member Distinguished Educators Council. That group urged expanded training for new teachers and more rigor in selecting teacher mentors.

“We strongly believe educators should be at the forefront of our education policy change conversations,” says Hildick. “We have done our work if teacher and leader voice is at the center of critical education policy conversations in our state.”

The North Clackamas School District and its teachers last year began work on a plan that led to a $1.4 million grant from the state’s School District Collaboration Fund.

Maureen Callahan, the district’s executive director of teaching and learning, has been impressed by the way teachers “have taken ownership of the project. They considered all the elements of our system in decision-making, and have been very thoughtful about what the research says is most effective. They’re leading from the ground up.”

She says district educators have shown an early interest in refining standards for professional development that recognize different needs for different teachers.

The project team includes 60 of the district’s 850 teachers, representing a broad cross-section of voices and interests. District Superintendent Matt Utterback says inclusion is critical to success.

“We’re creating a stronger system because it includes the teacher voice in the design and implementation,” he says.

As districts around Oregon engaged the CLASS Project, they identified another need. To help administrators support teachers and students, Chalkboard created the Leading for Learning initiative.

“The second most important factor with teacher effectiveness is the principal, and how well that person is equipped to support the teachers,” says Erin Prince, a former educator, administrator and now Chalkboard’s vice president of education policy.

Leading for Learning supports two populations — aspiring administrators, who often are teachers, and current administrators.

“The main focus is on instructional leadership, for both current and aspiring administrators” Prince says. “The most effective leaders are those who have a strong grasp of instruction.”

Current leaders participate in a leadership training program to deepen and build central office capacity to better support principals and schools, and empower school principals to improve student achievement and support teachers.

Iton Udosenata, principal at Cottage Grove High School, joined the leadership discussion when Krista Parent, superintendent of the South Lane School District, asked him to take part in the Distinguished Leaders Council.

Iton Udosenata, principal at Cottage Grove High School.

Udosenata says Aspiring Leaders helps ensure that future administrators work with people experienced in their future area of responsibility — be it alternative ed, curriculum, middle school or high school. A unique feature of the pilot program is paid release time during the school day to work with school administrators.

As Oregon’s population becomes more ethnically diverse, Chalkboard is also working through its Leadership initiative to ensure culturally diverse leaders.

“Aspiring Leaders is trying to get at least 50 percent of the cohort from historically under-represented populations,” says Udosenata.

He says the support provided through Chalkboard is a major reason Cottage Grove High rates as a Level 5 school in performance tests and graduation rates, which approached 90 percent two years ago.

“That’s because of our focus on instruction and having teachers and administrators collaborate for professional development,” he says.

Hitz, the PSU dean, heaps praise on Chalkboard for moving the needle.

“Absolutely, Chalkboard has made a huge difference,” he says. “But we have a lot of work to do. We haven’t figured out a way to give teachers more time so they can work together.”

Echoing his sentiments after nearly four decades in the trenches, Sue Dickman says the job facing teachers has grown more difficult.

“The demands on teachers are much greater,” says the former sixth-grade instructor. “We have to figure out ways to support teachers and education. We’re falling down on that in Oregon.

FUNDING PARTNERS OF FOUNDATIONS FOR A BETTER OREGON / CHALKBOARD PROJECT

A-dec

Leo Adler Foundation

Braemar Charitable Trust

The Gray Family Foundation

The Jackson Foundation

Helen K. and Arthur E. Johnson Foundation

Samuel S. Johnson Foundation

JFR Foundation

PGE Foundation

The Robert D. and Marcia H. Randall Charitable Trust

The Renaissance Foundation

Reser Family Foundation

Harold & Arlene Schnitzer CARE Foundation

Mr. John Shipley

Ann & Bill Swindells Charitable Trust

The Rose E. Tucker Charitable Trust

The Tykeson Family Charitable Trust

Joseph E. Weston Public Foundation (OCF)

The Wheeler Foundation

The Whipple Foundation Fund (OCF)

Oregon Community Foundation

The Ford Family Foundation

James F. and Marion Miller Foundation

Meyer Memorial Trust

The Collins Foundation

Wendt Family Foundation (formerly the JELD-WEN Foundation)