Artificial intelligence will make lawyers hundreds of times more efficient and give a leg up to the firms that can afford the technology.

It wasn’t as flashy a display as I was expecting.

Kat Miller and Shiau Yen Chin-Dennis of K&L Gates’ Porltand Office present AI Software “Kira” during a video conference.

Kat Miller and Shiau Yen Chin-Dennis of K&L Gates’ Porltand Office present AI Software “Kira” during a video conference.

When I ventured to K&L Gates’ Portland office, investigating the law firm’s use of legal artificial intelligence software, I expected to find a room full of whirring computers, flashing screens and floating metal cubes.

What I got was a laptop, a few seconds of loading time and a long list of documents the system had determined to be relevant to the case.

Routine as the process might have looked, the machine-learning software called “Kira” was performing what is known as “predictive coding,” a revolutionary process that uses artificial intelligence to save lawyers time and resources when reviewing documents.

The program works by selecting keywords and phrases from documents a user has determined to be relevant to a case and cross-referencing them with words and phrases from documents deemed irrelevant.

The algorithm then takes what it learned and sorts through thousands, even millions, of other documents to determine if they are relevant to the case at hand.

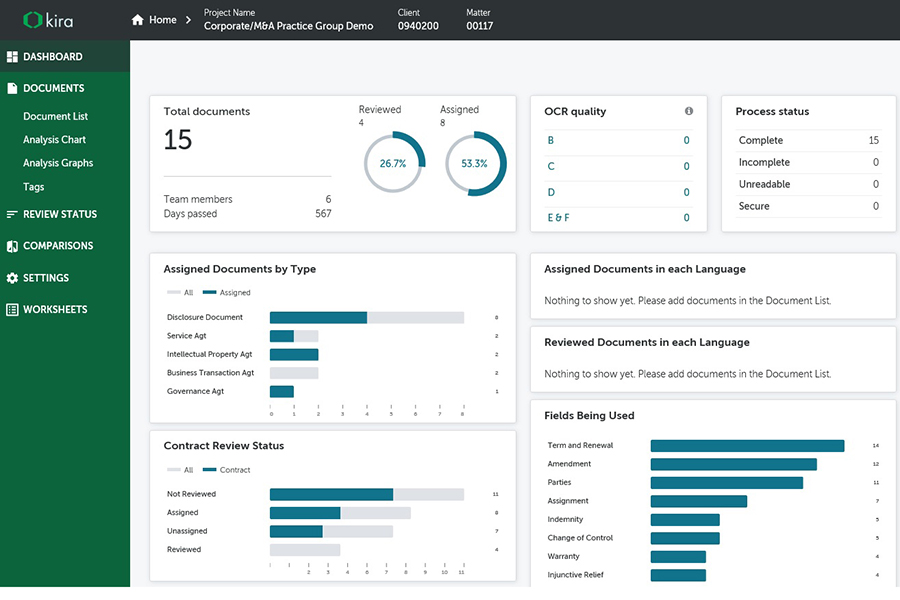

Screenshot of Kira’s dashboard

Reviewing thousands of legal documents in preparation for a case, often called “first-pass review,” used to be a time-consuming yet essential part of preparing for a case. Now, for the firms that can afford cutting-edge legal artificial intelligence software, such drudgery is a thing of the past.

Advances in machine learning will revolutionize legal work, making attorneys more efficient and providing new payment options that don’t include an hourly rate. But the costly technology could also create a gulf between the firms that can afford the software and smaller firms that do not have the resources to invest in it.

Law firms in the Pacific Northwest have been quick to embrace artificial intelligence. Bart Gabler, chief information officer at K&L Gates, says the firm’s Portland and Seattle offices were instrumental in the company’s adoption of machine-learning technology.

K&L Gates was also one of the early adopters of blockchain record-keeping systems back in 2017. “We have a great incubator for new technology in the Northwest,” says Gabler.

For many lawyers, the shift toward predictive coding is welcome, and the presence of AI in the legal field is not entirely new. “It used to be that junior lawyers would be stuck in a room with no windows and a huge stack of documents to review,” says Kat Miller, a lawyer at K&L Gates. “We’d much prefer to be at our computers working with the new technology.”

Though predictive coding is still relatively new, some earlier forms of legal AI, such as the legal-research programs Westlaw and LexisNexis, are already industry standards.

Instead of feeding Westlaw documents, a user can search for cases in Westlaw’s expansive database. Once the user has looked at enough cases, the machine-learning algorithm will suggest similar cases to review, much like music AI programs that generate songs based on users’ previous music selections.

Miller recalled how when she was in law school, her peers only spent one day in the file room learning how to search for cases without a computer. “They brought us into the dark room and said, ‘This is what you do if the power ever goes out.’ Then an hour later, we were back at the computer using Westlaw,” says Miller.

In 2017 predictive coding made a splash in the legal profession when JPMorgan announced its use of the artificial intelligence software Contract Intelligence, which processed in a matter of seconds documents that would have taken legal aides an estimated 360,000 hours to review.

While artificial intelligence is not impervious to error, it is more likely a human will miss a crucial piece of information during an initial document review.

A 2019 review by the American Bar Association found these software programs were more accurate and thorough than legal professionals.

This makes sense considering the amount a fatigue that can set in while performing 360,000 hours of document review.

In some cases, artificial intelligence can reduce the need for a lawyer altogether.

Credit: Joan McGuire

Credit: Joan McGuire

Take Wevorce. For less than $1,000, users can employ the legal technology company’s specially tailored artificial intelligence software to generate an equitable divorce settlement — a process that, when lawyers are involved, could cost $15,000 per person.

Wevorce hasn’t taken a sizeable bite out of divorce lawyers’ business yet. The average annual income for a family lawyer in 2019 was $82,000, up from $71,000 five years ago.

While AI software might remove the need for lawyers in certain instances, it could also open up new opportunities for legal services.

For example, with the rise of big data, even small companies could find themselves acquiring entire hard drives full of contracts. A firm with predictive coding could scan all of a company’s contracts for holes and technicalities.

Matt Scherer is an expert on artificial intelligence in the legal profession. A Portland-based lawyer at Littler Mendelson, he is the author of “Regulating Artificial Intelligence Systems: Risks, Challenges, Competencies and Strategies,” published in the spring 2016 issue of the Harvard Journal of Law and Technology.

He has a growing family and works remotely much of the time. “It’s interesting because, back in the day, it used to be that smaller law firms were better family jobs, but now it’s the bigger firms that are easier for having a family,” says Scherer.

“All the access to technology means so much of the job can be done remotely.”

Scherer says that while other uses of artificial intelligence exist in the legal profession, performing first-pass document review is still considered to be the gold standard of predictive coding. It is also the application that has the most potential to shake up the industry.

Automated document review processes also eliminate a large source of financial burden for a client. “The biggest pain point for clients during the litigation process is on document requests,” says Scherer.

“It used to be you would hire an army of contract attorneys and bill by the hour. Now much of that process can be automated.”

More often, in part due to artificial intelligence review, big-name clients have begun moving away from an hourly rate model of paying for legal services. In 2017 Microsoft announced it would be shifting away from paying an hourly rate for legal services, instead electing to pay a sum based on the type of service provided.

“Clients want alternative fee arrangements because they expect more efficiency. They don’t want to pay hourly rates for a bunch of junior associates or non-lawyers to sit down and do repetitive work,” says Jon Washburn, chief information security officer at Stoel Rives.

“What we’re starting to see is clients wanting to pay a fee based on the overall service they receive.”

Ironically, some law firms use artificial intelligence software to generate their fees based on the average cost of similar legal services.

While first-pass review is the most potent use of legal artificial intelligence software, it is not the only way machine learning can assist lawyers. Predictive coding can also look at how judges have ruled in similar cases, and can offer advice on whether or not a client settling a dispute out of court could save money in the long run.

AI programs also have the ability to predict what cases an opposing counsel might use against you.

And more advancements could be on the horizon.

Leesa Lee is the marketing director of LawGeex, a company that produces software for legal professionals. The technology uses predictive coding to scan contract documents for hidden costs that its clients may incur down the line.

Credit Joan McGuire

“We are still very much in the nascent stages of AI’s use in the practice of law,” says Lee. “I think the next step in development is going to be a system able to accomplish natural language processing.”

According to Lee, the technology still has a lot of room for growth, and changes brought about by this kind of growth are inevitable.

As it stands now, the use of legal artificial intelligence is prevalent but by no means everywhere. The least expensive predictive-coding programs can cost from around $30,000 to accommodate 10 users to upwards of $250,000 for a large office.

For smaller law firms and nonprofits, the technology is either too expensive or does not suit their needs.

The American Bar Association has proposed model rules that would require a lawyer to be familiar with the benefits and risks specific to relevant technology.

The Oregon State Bar does not have a specific technology mandate in its rules, though it does require lawyers to be familiar with the technological aspects of the cases they handle. The extent to which this requirement applies to predictive-coding technologies is not entirely clear.

But the technology is becoming hard to ignore, according to John E. Grant, who sits on the board of governors for the Oregon State Bar. Grant served as chair on the innovations committee, and warns the coming age of legal AI could mean a case’s outcome could hinge even more on a client’s ability to pay.

“Part of our mission is to ensure access to legal services and the fairness of the justice system,” he says. “We need to be conscious of how the balance is affected if one side can go out and buy a better arsenal.”

-John E. Grant, board member of Oregon State Bar

For some legal professionals, predictive coding has not come far enough to be useful yet.

“Part of our mission is to ensure access to legal services and the fairness of the justice system,” he says. “We need to be conscious of how the balance is affected if one side can go out and buy a better arsenal.”

Theo Erde-Wollheim is a criminal defense attorney at a nonprofit law firm. He says that cost is not the only reason he is unable to use artificial intelligence in his practice. Even though the technology has a lower rate of error than a human, if the system did make some sort of mistake, the onus would still be on him.

“There’s an entire system of addressing grievances for clients who feel like they haven’t been properly represented,” says Erde-Wollheim. “If a machine messes up and it misses something, I’m the one who has to answer for it.”

Given the heavy caseload of criminal defense attorneys, artificial intelligence might be able to assist one day, but there is still information that AI software cannot assess yet. It is unable to analyze video evidence, such as police body cameras, and also does a bad job coding natural language, such as the kind used in audio transcriptions.

Moreover, criminal defense lawyers often need to paint a picture of their client to a judge or jury to help frame the client’s alleged actions, something artificial intelligence may never be able to accomplish.

While Erde-Wollheim says legal-research AI programs like LexisNexis and Westlaw have become industry standards, for lawyers like him, the human element is still more important than ever.

For now, predictive-coding software is only available to large and medium-sized firms with enough of a caseload and large enough workforce to take advantage of it. Smaller firms might be able to provide a more personal touch, but for big-money civil litigation, artificial intelligence isn’t just being used, it is being demanded.

The creeping question remains, just how much of a lawyer’s job — or any legal professional’s job, for that matter — can be automated? Will legal professionals have to compete with robots to keep their jobs?

According to a 2016 report by consulting firm Deloitte, approximately 114,000 legal jobs (36% of the profession) could disappear by 2036 due to automation. The study claimed secretaries, law clerks and paralegal jobs to be most at risk.

A different report by McKinsey & Company found approximately 22% of a lawyer’s job can be accomplished by artificial intelligence, compared with 35% of a law clerk’s duties.

According to Lee, there is no reason to believe automation will eliminate legal jobs completely. “Just because a machine can do 22% of a lawyer’s job doesn’t mean there are going to be 22% fewer lawyers,” says Lee. “Artificial intelligence just makes lawyers more effective at lawyering.”

The numbers seem to agree with Lee’s assessment. Paralegal jobs are expected to increase 12% over the next decade, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. A report by the National Association for Law Placement found law school graduates’ employment prospects to be close to 90%, the highest since the 2008 recession.

The day will inevitably arrive when predictive-coding software, much like legal-research tools such as Westlaw, will be so widespread, they will not be cost prohibitive for smaller firms. When that day comes, the tools will become indispensable in the practice of law, says Lee.

Scherer takes the argument a step further. He argues artificial intelligence software will become so good at discovering documents relevant to a client’s case that not having an artificial intelligence program perform document review could be considered negligent.

“It’s not unlike the practice of medicine, where not using an AI system to evaluate a radiology scan could be considered medical malpractice,” he says. “If you’re not using the technology and you’re missing important stuff, you won’t be meeting the standard of care that’s expected of a professional.”

That future may be arriving sooner rather than later.

Last November ROSS Intelligence, a legal AI developer, announced an access program for law students around the country, ensuring every student with a law school email address will get a taste for the next generation of predictive-coding tools.

Predicting Justice

While lawyers using algorithms to review documents has the potential to upend the legal profession, predictive coding has not faced much ethical scrutiny. This may change if machine learning is increasingly used for sentencing.

The method, known as evidence-based sentencing, uses automated algorithms to boil down an offender’s background to data points and assess how likely the criminal is to reoffend.

The practice has been outlawed by numerous states and counties for alleged racial bias. More than 100 civil rights activists and community organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, have called for the abolishment of predictive tools used for sentencing and parole hearings, citing the programs’ high error rates when assessing defendants of color.

Oregon has not banned the practice. Between 2000 and 2005, the Oregon Department of Corrections and Oregon Criminal Justice Commission analyzed data from 55,000 offenders to develop the Oregon Public Safety Checklist, an automated risk-assessment tool intended to inform sentencing and parole hearings.

The tool evaluates defendants on 11 risk factors, including age, gender, type of crime committed and previous arrest history. Unlike more controversial tools, ethnicity is not factored into the equation. The tool also does not suggest a prison sentence, merely an offender’s risk of recidivism.

But predictive coding can also be used to grant clemency. The State of Oregon Statistical Analysis Center receives support from state funding and the Bureau of Justice Statistics, with the goal of using data to inform and improve criminal justice.

The Yamhill County Justice Reinvestment program uses these funds to employ the Women’s Risk Needs Assessment, an automated scoring tool specifically designed to analyze a female inmate’s history of trauma, abuse and mental health when determining criminal justice outcomes.

Additionally, House Bill 2355 mandated that by 2021, all Oregon law-enforcement agencies must submit police officer-initiated traffic and pedestrian stop data to the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission to evaluate racial or ethnic disparities.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.