Is Measure 97 the end of days? Or will the controversial tax measure lead to a new era of cooperation and compromise?

Emily Powell, the third-generation owner of her family’s namesake bookshop, isn’t interested in talking about other ways for the Oregon Legislature to increase revenue in the face of Measure 97, the corporate gross receipts tax on the November ballot.

“We’re not willing to discuss alternatives at this time. It’s a poorly thought-out idea, and it must be defeated before we can come up with another plan,” she wrote in an email after intercepting an interview request for Powell’s CEO, Miriam Sontz.

Powell, who took over the iconic bookstore from her father in 2010, has said the tax threatens the company’s existence. Wholesalers and utilities will likely raise the prices she pays to recoup their portion of the tax, she has said, but Powell’s has little wiggle room on book prices because of stiff competition from internet rivals.

The ballot measure, previously known as IP28, would place a 2.5% tax on large and mostly out- of-state companies that have more than $25 million a year in Oregon sales. It is expected to bring in $6.1 billion in the 2017-19 biennium and lead to a loss of 38,200 private-sector jobs by 2022 while creating 17,700 government positions.

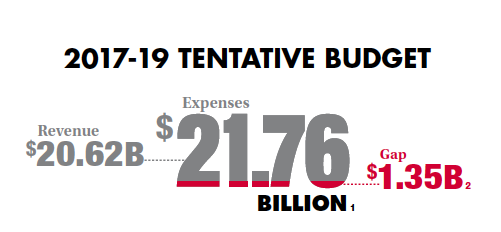

Powell is hardly alone in her opposition. All the state’s major business associations — the Oregon Business Association, Associated Oregon Industries, and the Portland Business Alliance — are opposed to the measure and have mounted expensive campaigns to fight it. The proposal comes as businesses are adapting to the July 1 minimum-wage increase and integrating the new sick-leave requirements that started in January. Supporters, meanwhile, point to a projected $1.35 billion state budget deficit and its deleterious impact on schools and social services.

The divide

At its core, Measure 97 reflects a divide between the Democratic legislators and labor groups, who don’t want education and social service cuts, and the Republican legislators and business leaders who don’t want revenue increases. In her Aug. 4 endorsement of Measure 97, Gov. Kate Brown said the measure was necessary because the state’s business community and legislators had failed to find a common taxable ground.

Interviews with business owners and representatives did yield several long term revenue proposals the state has bandied about for decades but never implemented: namely, a sales tax. Measure 97 opponents also cited a need to eliminate corporate tax breaks and better financial accountability on the part of politicians. But the overarching business response to Measure 97 is best expressed by Emily Powell: No. We don’t want it.

Past examples of collaboration between tax foes and supporters exist; witness the coalition that formed after Portland State University withdrew its controversial payroll tax last spring. In lieu of that kind of compromise, Measure 97 comes as no surprise: In the absence of public and private sector leadership, the popular vote will fill the void.

Will business lead on tax reform?

Ask any business leader what they think about enacting tax reform in Oregon — as an alternative to Measure 97 — and almost all will say the same thing: Maybe, but it must be accompanied by a review of how the state is collecting its money and which taxes are effective. A sales tax has failed countless times. But still it’s a good idea, many say, that would let the state benefit from economic booms and still bring in cash from everyday spending during downturns.

“A sales tax is a way to smooth some of the bumps,” says Roger Lee, head of Economic Development for Central Oregon (EDCO), with a nod to tourists helping heft the state’s tax burden. “You could do all kinds of things with a moderate sales tax of 4% to 5%.”

One of those things includes doing away with the state’s corporate income tax, he says during a phone interview from his Bend office. But Lee doesn’t believe business leaders or even voters should help the government out of its fiscal hole. “That’s the job of legislators,” he says. “Our legislature and especially our executive branch aren’t willing to do significant tax reform.”

About that corporate income tax: Our Oregon, the union-backed group that crafted IP28, likes to say that the state has the lowest corporate income tax in the country. Although that’s true by some measures, it’s also an oversimplification. As Eric Fruits, a Portland economist who runs his own consulting business observes, Oregon’s business tax is low but the state has comparatively high fees.

The state has a high personal income tax, high capital gains taxes for wealthy individuals and high property taxes, Fruits says. These levies put the state in the middle of the pack nationally: The Washington, D.C., think tank the Tax Foundation says the state’s per-capita corporate tax burden puts it in 28th place, while Oregon’s own Legislative Revenue Office, the same office that projects a budget deficit in the next binennium, puts it at 26th.

Fruits isn’t convinced state government will run a deficit, and he says avoiding recent government disasters such as the Cover Oregon health exchange debacle could have gone a long way to halting the fiscal bleeding. “I don’t think it’s axiomatic to say there’ll be this huge budget shortfall. There will be budget challenges,” he says. “It’s time to have a conversation.”

Greg Cowan, owner of Castelli USA, the U.S. unit of Italian cycling-clothing maker Castelli, agrees with Fruits that Salem should be more mindful of its purse strings. He says a sales tax is impractical and has been repeatedly shot down. Legislators would also have to promise to lower property or income taxes to get one passed.

“If you’re going to trade taxes, you really have to trade,” Cowan says during an interview in his office, where he is surrounded by posters of cycling heroes past and present. “The first step is the government has to evaluate their budget and their spending. They’ve made promises they can’t keep.”

Many Measure 97 opponents reject its fundamental premise: that the state doesn’t have enough money to fi ll alleged funding gaps. Salem’s budget has grown from $12.4 billion in the 2009 biennium to $17.7 billion in the current two-year period, yet the most recent state budget analysis projects a $1.35 billion shortfall in the 2017-19 biennium.

Businesses opposed to the measure also say many of the state’s fi nancial problems — such as a projected $870 million shortfall in the Public Employees Retirement System (PERS) — have been known for years if not decades, and that it is incumbent on legislators to fi nd solutions. The expansion of Medicaid under President Obama’s Affordable Care Act has been another drain on state coffers.

Our Oregon, disagrees and says the bottom line is public services, schools in particular, need more money. The state spent $10,996 per student in the 2014-15 school year, less than the national average of $12,296, according to the Oregon Department of Education. Oregon schools rank 39th nationally in per-capita student spending and 38th in performance, according to an Oregonian review of test scores and graduation rates. The corporate receipts tax is the most equitable solution, says Our Oregon spokesperson Katherine Driessen. “These are businesses that have the ability to pay higher taxes.”

The former Nike executive says Measure 97 would have minimal impact on his business but sends the wrong message to companies active in Oregon, because it accuses them of not carrying their own weight. “I just don’t see business — whether it’s big or small business — as an adversary,” he says.

Corporate tax breaks

That said, Cowan adds he and other small- and medium-size businesses would like to benefit from the kinds of tax breaks offered to big corporations like Intel and Nike. At the very least, ending the breaks would even the playing field and bring in more cash for the government.

Publicity around corporate tax breaks and subsidies helped set the stage for Measure 97. In 2012-13 former Gov. Kitzhaber signed controversial 30-year deals with Nike and Intel that codified an existing practice of only levying corporate income tax on their Oregon sales rather than total sales. Large local companies like Powell’s can’t benefit from such agreements since their sales are primarily in-state.

These agreements cost Oregon $164.9 million between 2013 and 2015, according to state revenue figures. What’s more: In 2013 Portland reportedly offered Nike an $80 million incentive package to locate extensive operations in the city’s southern waterfront area. The shoemaker didn’t accept, preferring instead to stay in an island of unincorporated Washington County that isn’t subject to the taxes of the surrounding city of Beaverton.

Growing the economy

Eliminating corporate tax breaks is one way to shore up public coffers. But many businesspeople think the smartest solution is to boost tax receipts the old-fashioned way: by growing the economy. The problem with Measure 97, says Monica Enand, founder, president and CEO of legal-software maker Zapproved, is that it will unfairly hit tech startups, as well as their high salaries, at a time when Oregon is experiencing a software boom, she says from her seventh-floor Pearl District office.

Since the tax only looks at sales and not profit, large, unprofitable technology companies would have an even harder time getting into the black in Oregon. And selling a relocation to Oregon to deep-pocketed venture capitalist owners could be tough with a 2.5% gross receipts tax. “They have to believe Oregon is an attractive place,” Enand says. Measure 97 and other measures such as minimum wage and sick leave have offered a false perception of the state: “the perception that the government isn’t trying to grow the economy.”

However, Enand does believe the government may need more money — and she says she’s willing to sit down and help the legislature find a solution.

A model collaboration?

In the cacophony surrounding Measure 97, one joint solution designed to prevent a proposed tax increase has generated surprisingly little publicity. The Portland Business Alliance (PBA) this spring was part of a consortium that convinced Portland State University to withdraw a proposed payroll tax designed to raise $35 million annually for PSU scholarships.

Instead a new organization, the Coalition for Access & Affordability, will hunt for $25 million in new and existing funds to back higher education throughout Oregon. The coalition will work with government and school officials to offer new incentives for donations, lobby to redirect existing funds to scholarships and possibly propose new taxes in the future.

Portland’s business community not only openly opposed the payroll tax proposal, it also proactively reached out to PSU to prevent it. The joint effort could be a model for future reform, says PBA’s CEO and president Sandra McDonough. McDonough says she’s always willing to help legislators craft new taxes — if they really need the cash.

“Tax policy is very complex. What we have right now is one interest group that’s trying to impose something bad on Oregon,” she says. “It needs to be a lot of partners around a table coming up with some ideas. We never had the opportunity to sit at the table.”

The PBA has supported an increase in corporate income taxes in the past, and McDonough generally promotes new bonds for schools. But she says her organization — and organizations like it around Oregon — need to be part of any new tax reform, just as they have been in the past. “When we were talking with Gov. Kitzhaber, we looked at a broad array of things, but you can’t just look at revenues; you also have to look at spending,” she says.

Measure 97 supporters say the gross receipts ballot measure couldn’t have been an unexpected move for Oregon businesses. “I’m surprised that they’re surprised,” says Our Oregon spokesperson Katherine Driessen. “They’ve been at the table, and they were well aware of the problem.”

While Gov. Brown is throwing her support behind 97, one Republican legislator says she is still willing to discuss different proposals — as long as the government will take a look at its spending. Rep. Julie Parrish, (R-Tualatin/West Linn,) is running for her fourth term in November and wonders just what happened to the $5 billion increase in the state’s budget during her tenure.

“I never took a no-new-tax pledge. If we’re really good with our money and came back and said we’re short $1 billion, then we can talk,” Parrish says during an evening phone interview, her husband helping her son with a babysitting job in the background. Parrish says she is open to discussions about tax reform: “But our plan should revolve around how to be smarter with the money we have.”

The zeitgeist

Like all ballot measures, Measure 97 at some level signals a failure of the legislative process. It also seems calibrated to the current local, national and international zeitgeist, defined by a disgruntled electorate and populist revolt: Witness the Republican primaries, the U.S. presidential election, the U.K’s departure from the EU.

It may seem hyperbolic to link Measure 97 to the political sentiment that produced Donald Trump and Brexit, although a link to Bernie Sanders is probably apropos. Besides, anybody who heard Sen. Peter Courtney (D-Salem) deliver his thunderous speech during the Oregon Business Summit last December knows these are hyperbolic times.

“There are all kinds of civil wars. Oregon is on the verge of its own civil war — the war of the ballot,” Courtney boomed. “And while we may not physically kill one another, the consequences of next Nov. 8 could be our version of Antietam: potentially the bloodiest political day in Oregon history.”

If the measure passes, it will be, to use another war metaphor, the business community’s Waterloo. If it fails, we’re back to square one on revenue: gridlock. Is there a third way?

In the past, Gov. Kitzhaber was adept at leading opposing parties to a compromise, says Jim Moore, a political science professor at Pacific University. But that kind of leadership is missing, Moore says. Neither side has to come up with a revolutionary idea to bridge the ideological gap; there are 49 other states, and at least one must have a combination of taxes, spending and economic development that Oregon can lean on, Moore says. “Let’s come up with something that works, modeled on some other state,” Moore says.

Perhaps Measure 97 can act as a catalyst, a peacemaker, to get everyone out of the trenches and back to the bargaining table to find an equitable solution. If not: The ballot measure may be only the first of many bloody skirmishes, with no end in sight.

A version of this article appears in the September issue of Oregon Business