BY JOE ROJAS-BURKE & KIM MOORE

Oregon Business reports on the visa squeeze, the skills gap and foreign-born residents who are revitalizing rural Oregon.

Oregon Business reports on the visa squeeze, the skills gap and foreign-born residents who are revitalizing rural Oregon.

As Immigration Reform Stalls, Businesses Struggle to Find Workers

BY JOE ROJAS-BURKE | PHOTOS BY MEGHAN NOLT | ILLUSTRATION BY NEIL SHRUBB

Immigration reform seemed to be making progress. A comprehensive bill, backed by four Republicans, cruised through the U.S. Senate last year. It included requirements for building 700 miles of border fences, adding 38,000 more border-patrol agents, and imposing harsh penalties on employers who hire undocumented workers.

At the same time, it cleared the way for significantly expanded immigration, with more temporary visas for skilled workers, more permanent visas for foreign science graduates of U.S. universities, and new opportunities for entrepreneurs and investors to come to the U.S. It also offered a path for 11 million undocumented workers to become permanent legal residents.

After House Republicans refused to support it, President Obama made impotent threats to use executive power to change the immigration system without Congress. The president backed down in September, when it became clear that the action might jeopardize Democrats in the upcoming election. Prospects for reform now seem distant as ever.

In Oregon, the issue has spilled onto the ballot in a fight over the state law giving undocumented immigrants legal driving privileges. The driver-card law passed last year with bipartisan support and the backing of wine growers, landscaping nurseries and the hotel and restaurant industry. But it immediately galvanized a grassroots opposition that qualified Measure 88, a referendum aimed at overturning the law, for the November ballot.

“To knowingly harbor someone here illegally is against federal law,” says Sal Esquivel, a real estate broker, Republican state representative from Medford and one of three petitioners for Measure 88.

“To knowingly harbor someone here illegally is against federal law,” says Sal Esquivel, a real estate broker, Republican state representative from Medford and one of three petitioners for Measure 88.

Immigration also broke out as a defining issue in the Oregon governor’s race. Rep. Dennis Richardson, a retired trial lawyer from Central Point who is challenging Gov. John Kitzhaber, opposed both the driver-card law and a law authorizing in-state tuition for undocumented immigrants. Kitzhaber championed both.

What can’t be ignored is that foreign-born, undocumented workers account for more than 5% of the state’s workforce. And agriculture is not the only industry that’s become dependent on immigrant labor. Bill Perry, vice president of government affairs for the Oregon Restaurant & Lodging Association, says undocumented laborers may account for 15% of the workforce in his industry, and perhaps as much in unskilled jobs in construction and home health.

|

| Jim Gilbert, co-owner of One Green World |

Nationwide, the number of undocumented immigrants peaked in 2007 at around 12.2 million. The number fell about a million during the Great Recession and has remained flat since 2009, causing acute labor shortages in Oregon’s vineyards, orchards and nurseries.

“It hurts. We’ve had to make some decisions to cut back just because of a lack of labor,” says Jim Gilbert, co-owner of One Green World, a nursery specializing in fruit trees and berries. The business needed a crew of about 50 over the summer but struggled to recruit more than 30.

Studies have repeatedly shown that low-skilled migrant workers do not compete with U.S. citizens for jobs, and that a broad swath of employers are being held back by immigration policies that don’t work well for anyone.

“Much of our immigration policy really doesn’t account for what we know about immigration,” says John Green, director of the Center for Population Studies at the University of Mississippi.

Is Skills Gap about Immigration—or Education?

BY JOE ROJAS-BURKE

For all the talk about America’s shortage of scientifically skilled workers, the nature of this “skills gap” is hard to pin down.

Are U.S. schools cranking out too few graduates in the STEM fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics? Or do more attractive jobs lure too many U.S. students away from these fields? Should the government expand immigration to pump up the labor supply with foreign-born talent? Or should it allow market forces to work while investing more in education and training?

“There’s a lot of debate over whether there is a STEM shortage or not. It’s pretty unclear,” says Neil Ruiz, a senior policy analyst with the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit think tank in Washington, D.C.

At first glance, colleges and universities appear to be producing more than enough graduates. But Americans with technical training often pursue other careers. Half of college grads with engineering degrees don’t work in that field a year after graduation, and the same is true for about a third of computer science grads, according to Rutgers University professor Hal Salzman’s analysis of National Center for Education Statistics.

American science and math graduates who choose non-STEM careers may be doing so for good reasons. The offshoring of technology jobs, which seems to make headlines every month, is not a reassuring trend. High-paying Wall Street firms and other employers are eager to snap up brainy graduates for jobs outside of their science majors. Jobs in science and engineering are projected to grow by about 1.3% a year over the next decade, a bit faster than the 1% projected growth for all jobs, the Congressional Research Service reported. But average wages for science and engineering jobs aren’t growing any faster than the average for all occupations. After adjusting for inflation, life scientists’ earnings actually fell between 2008 and 2012, and overall wages for science and engineering jobs grew by less than 1%.

American science and math graduates who choose non-STEM careers may be doing so for good reasons. The offshoring of technology jobs, which seems to make headlines every month, is not a reassuring trend. High-paying Wall Street firms and other employers are eager to snap up brainy graduates for jobs outside of their science majors. Jobs in science and engineering are projected to grow by about 1.3% a year over the next decade, a bit faster than the 1% projected growth for all jobs, the Congressional Research Service reported. But average wages for science and engineering jobs aren’t growing any faster than the average for all occupations. After adjusting for inflation, life scientists’ earnings actually fell between 2008 and 2012, and overall wages for science and engineering jobs grew by less than 1%.

In Oregon there is evidence of an acute shortage. High-tech entrepreneurs and executives say it can take months to fill high-paying jobs. “It’s extremely difficult — it’s impossible — to recruit all the talented engineers we need just in the U.S.,” says Wally Rhines, CEO of Mentor Graphics Corporation, a maker of software tools for designing computer chips and circuits. Firms that hire foreign guest workers typically say it’s an option of last resort, not an ideal long-term solution. In a survey last year by the Technology Association of Oregon, 86% of CEOs of local tech companies said they were facing a moderate or significant shortage of skilled workers.

About a third of Oregon’s STEM graduate degrees, and 60% of engineering Ph.D.s, go to foreigners on temporary student visas. Many who would like to go to work here can’t. Demand for H-1B visas, a temporary permit for workers with technical expertise, far outstrips the 85,000 the U.S. allows each year, including 20,000 reserved for guest workers who have earned a master’s or doctoral degree from a U.S. school.

Cloudability Inc., a rapidly growing software firm, hired Oregon State graduate student Anushree Sharma, a native of India, and tried to secure her full-time but couldn’t obtain a visa. “She was an amazing employee,” says CEO and founder Mat Ellis. “There was just no way to keep her.” Sharma was snapped up by a company in India, and Cloudability spent seven months trying to fill the job. “These jobs are not getting filled, and that money is not being spent in this community,” says Ellis, himself an immigrant from the United Kingdom.

|

| Mentor Graphics received 68 approvals for H-1B visa positions in 2014. |

Rhines, the Mentor Graphics CEO, says his company recruits globally for the best people, not the cheapest. The company advocates for expanding immigration to make it possible to fill key positions in the U.S. “It’s about putting people with critical skills to work for your company,” Rhines says. “If we can’t hire them in the U.S., we have to hire them somewhere.”

Critics of expanding guest worker visas say that doing so would drag down wages and dissuade even more American students from pursuing engineering and scientific training. They argue that market forces can do an adequate job of boosting labor supply. Salzman, the Rutgers professor, says that when the rapidly expanding oil industry ran short of petroleum engineers, companies boosted the pay for new graduates by 40% over five years, and the number of new graduates more than doubled.

But technology employers say guest workers aren’t suppressing wages, because they have to pay more for foreign talent, not less, in hard-to-fill jobs. Testing that claim, Ruiz, the Brookings Institution analyst, compared 2010 wage data and found that H-1B workers earn more than Americans matched by job type and age.

Importing foreign talent isn’t the only option. In fact, less than a quarter of Oregon tech CEOs said they would be “very likely” to pursue temporary foreign workers if the supply became more available, according to the Technology Association of Oregon survey. Companies are interested in working with colleges and universities such as Portland State to offer applied learning experiences and to align curricula with the skills companies are looking for, says Skip Newberry, president of the Technology Association. Oregon firms also are focusing on stepping up marketing and recruiting to attract talent from other cities.

But such efforts can only go so far, says entrepreneur Kanth Gopalpur, founder of the software company Monsoon. The long-term solution, he says, is a sustained investment in the state’s chronically underfunded education system. “But this is a decades-long process, and there is a lack of leadership in both private and public sectors to make that long-term investment.”

That may be true, but alarm about America’s skills gap is also a reflection of national anxieties, just as it was in the 1950s after Russia launched its Sputnik satellite into orbit, and in the 1980s when Japan’s manufacturing prowess seemed unstoppable. A shortage of scientifically trained people may not be the root of the problem, and if it isn’t, immigration can’t be the whole solution. The issues run deep: structural changes in the world economy, what’s really driving companies to offshore operations and the cultural values that shape young Americans’ career choices.

Foreign Tech Talent Trickles In

BY KIM MOORE

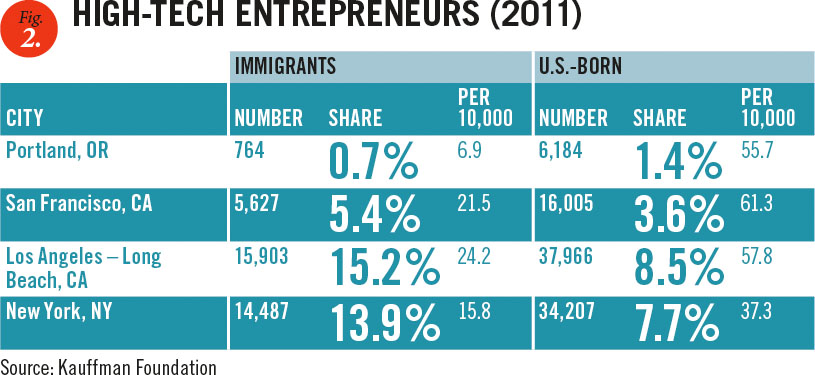

Portland is rapidly growing as a technology hub, with many new startups taking root in the city. But it is still not as strong a magnet for attracting foreign-born technology entrepreneurs as other tech hubs, such as San Francisco and Seattle.

Portland had only seven high-tech immigrant entrepreneurs per 10,000 of the population in 2011, according to data from the Kauffman Foundation. San Francisco, had three times as many. Only Detroit, Mich. Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minn., and Philadelphia, Penn., had fewer high-tech immigrant entrepreneurs of the 25 largest metropolitan cities surveyed by the organization. Nationally, immigrants comprise 20% of the high-tech workforce and 17.3% of high-tech entrepreneurs.

Portland may have attracted many more foreign-born tech entrepreneurs in the past couple of years, which is not reflected in the Kauffman Foundation’s data from 2011. But anecdotal evidence suggests the city still has some way to go to attract tech talent from overseas.

Nitin Rai, president of TiE Oregon, a network for entrepreneurs, says he hasn’t seen much of an increase in foreign-born tech entrepreneurs moving to the city. He blames this on Portland lacking visibility as a center for technology innovation. “Oregon needs to market itself to attract talent. Part of that is immigrant talent,” says Rai, who is president and chief executive of First Insight Corporation, a software company.

Many of the new tech startups in Oregon “don’t have the marketing power” to hire foreign-born immigrants, says Rai, adding there are few large technology employers and universities in the state that have the resources to attract immigrants.

Intel, the chip maker, is an exception. It employs 17,000 people in Oregon, making it the state’s largest private employer. Its branches in California, where it is headquartered, received 3,722 approvals for H-1B visas in fiscal years 2013 and 2014. Data for Intel’s Oregon H-1B visa approvals are unavailable.

Visa Squeeze

BY KIM MOORE

Demand for H-1B visas has jumped over the past few years as the economy improves and employers seek to fill positions that require specialized skills. H-1B visas are for positions that require a bachelor’s degree or higher and are in a specialty occupation.

The number of jobs in Oregon that companies requested to fill with H-1B visa holders grew 73% between 2010 and 2012. The number of certified H-1B positions increased 75%. Nationally, the top three certified H-1B positions were in computers and electronics engineering.

The U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services (USCIS) limits the number of H-1B visas it awards to foreign workers to 85,000 a year. Of these, 20,000 are awarded to holders of U.S. master’s degrees. In April this year, when companies could file applications for H-1B visas for the following year’s quota, the government received twice as many applications than visas available.

Applying for H-1B visas is expensive. It can cost a business up to $10,000 in filing and legal fees for one application. The fact it costs so much “reflects the need for foreign professional workers who have specialized skills,” says Alan Perkins, an attorney at Tonkon Torp’s immigration practice. [See accompanying article on skills gap.]

While demand for H-1B visas has increased, the number of applications employers filed to obtain permanent residence for their employees declined 45% between 2010 and 2012. Total certified positions decreased 51%. Companies typically apply for permanent residence for their employees after they have worked in the U.S. on an H-1B visa. The slowdown could be due to the fact more employers have not been able to obtain H-1B visas, says Gretel Ness, an attorney for immigration law firm Parker, Butte & Lane.

The number of applications for short-term or temporary foreign agricultural labor pales in comparison with the number of applications for skilled jobs in the technology and engineering sectors. H-2A labor certification is granted for activities lasting 10 months or less. Most occupations require unskilled or low-skilled labor. A total of 88 of these jobs were certified in 2012, a 76% increase over 2010.

The number of applications may not adequately represent the number of foreigners working in agriculture, however. Nationally, it is estimated about 50% of the agricultural workforce is undocumented, according to an official at the Oregon Department of Agriculture. Total positions certified for H-2B visas, which are for foreign workers who do temporary, nonagricultural work on a one-time, seasonal basis, fell 18% between 2010 and 2012.

Investors Blow Permit Cap

BY KIM MOORE

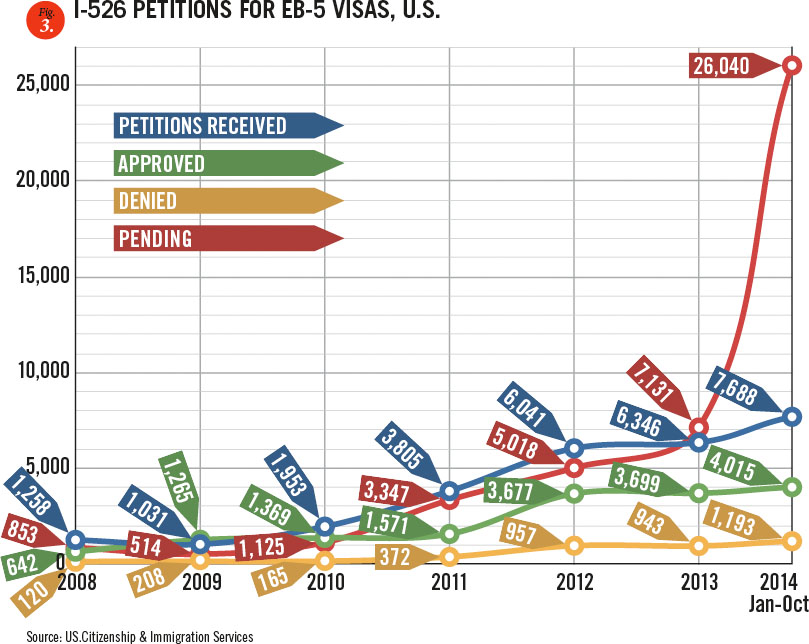

The EB-5 visa program has been a way for wealthy foreign-born investors to immigrate to the U.S. since 1992. But for the first time this year, the number of investor visas available to Chinese applicants — who account for the majority of applicants — exceeded available supply for fiscal year 2014.

The U.S. issues approximately 10,000 EB-5 visas a year. EB-5 visas are available to applicants who invest $500,000 to $1 million in a commercial enterprise in the U.S. The venture must either create or preserve at least 10 full-time jobs for U.S. workers within two years. Investors can also put their money into so-called regional centers that are either private corporations or regional government agencies that invest in a defined geographic area. USCIS lists nine regional centers in Oregon, including Columbia Willamette Investment and the Portland Regional Center. USCIS does not break down the number of EB-5 visas issued on a state-by-state basis.

Nationally, the number of foreigners obtaining lawful permanent-resident status in fiscal year 2013 through the EB-5 visa program was 8,543. Successful applicants receive a conditional permanent-resident card for two years and obtain permanent-residence status if the enterprise they invest in meets certain goals during that period.

Investors must file I-526 petitions to become eligible for EB-5 visas. The number of I-526 immigrant petitions by foreign-born entrepreneurs grew 225% between 2010 and 2013, showing the U.S. is a strong draw for wealthy overseas investors seeking to grow their money in commercial enterprises.

Newcomers Revitalize Rural Oregon

BY JOE ROJAS-BURKE

At age 15, Jose Cuna Vera left his home in Queréndaro, a rural village in the Mexican state of Michoacán, and made his way to Oregon. He would have liked to continue his education, but the family couldn’t afford it. “Life is the best school for you now,” he remembers his grandfather advising. Cuna Vera worked a succession of farm-labor jobs in the onion and sugar-beet fields of Eastern Oregon, and earned enough to wire money back home on a regular schedule to help his financially struggling family.

That was in 1989. These days Cuna Vera and his wife, both naturalized U.S. citizens, own a house in Ontario, where they are raising three children. From his start as a farm laborer, Cuna Vera moved on to work in onion storage and packing sheds, then spent many years in restaurant work, where he learned to love cooking. “I feel so happy when people come to eat my food. I feel like I did something important,” he says. Last October he started his own food-truck business, Don Pepe. He caters to a lunch and dinner crowd from a parking spot near the Outdoorsman, the local big-box sporting goods store.

“We come with big dreams,” he said at the end of a busy week in September. “We’re starting with this little truck, but one of my goals is trying to do my own restaurant.”

“We come with big dreams,” he said at the end of a busy week in September. “We’re starting with this little truck, but one of my goals is trying to do my own restaurant.”

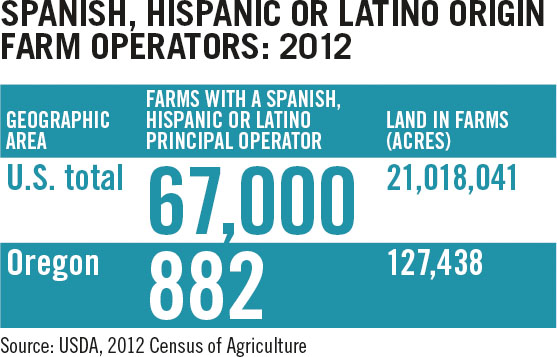

The immigration debate tends to dwell on the problems of border control and undocumented workers. But in farm country across Oregon and the U.S., upwardly mobile immigrants, largely from Mexico, have revitalized small towns long threatened by the inexorable loss of young people, who imagine better futures in urban areas and relocate to launch careers and start families. The loss of working-age people can trigger a downward spiral as local businesses lose customers and a shrinking tax base leaves towns short of money for maintaining schools, roads, parks and other services. In many rural communities, more people are dying than are being born.

“Hispanic in-migration is what’s keeping them alive,” says John Green, director of the Center for Population Studies at the University of Mississippi.

Oregon’s immigrant population from Latin America nearly tripled during the 1990s and continued to grow at a much slower pace for the next 10 years. Contrary to popular perception, a majority of Oregon’s Latino newcomers were born in the United States. More than 60% are U.S.-born citizens, according to the Pew Research Center. “Many of the Hispanics migrating to rural areas are doing so from other places in the U.S.,” Green says.

While only a fraction of Hispanic people in Oregon are undocumented immigrants, the population has climbed steeply, from an estimated 110,000 in 2000 to about 160,000 today. Most are employed and pay taxes, but the revenues probably don’t cover the full cost to local and state governments for schools, hospitals and law enforcement, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The burden, however, is modest. Spending for undocumented immigrants typically amounts to less than 5% of total local and state spending on those services, the CBO authors concluded.

And undocumented workers contribute more than tax revenues. They work in low-skill, manual -labor jobs that employers could not fill without them. Their purchasing power fuels local economies. And in farm communities emptied of working-age natives, the contribution of undocumented immigrants is magnified.

In Ontario, a town of fewer than 12,000, Latinos have accounted for all of the population growth since 2000. The non-Hispanic population dropped by nearly 10%, while the Hispanic or Latino-origin population grew by more than 33% between 2000 and 2010, as measured by the U.S. Census.

“They have started new businesses. Some run their own farms now. In years past, they were more of a migrant group,” says Ontario Mayor LeRoy Cammack. “These people have come to become permanent citizens of the community.”

Hispanic newcomers similarly prevented population losses in Boardman, Cornelius, Nyssa, Odell and Woodburn. In each of these small, rural communities, the number of people with Mexican or other Latin American roots now outnumbers non-Hispanic residents.

“People think we’re here to beg; we’re here to take. The truth is we’re here to contribute,” says Diego Castellanoz, whose grandparents immigrated from Mexico and settled in Nyssa, a town surrounded by sugar-beet fields near the Idaho border. Castellanoz, a city councilman and former town mayor, is a supervisor with the Amalgamated Sugar Company, where he’s worked for 30 years.

Nyssa’s Hispanic population grew by more than 9% between 2000 and 2010. Now nearly two-thirds of residents are Hispanic. “People here have seen what we can contribute. We have been embraced,” Castellanoz says. “We are like everyone else. We want to own a home, we want good schools. We want our kids to make a decent living.”

The demographic turnover in small towns hasn’t proceeded without conflict. As established as the Latino community is in Nyssa, Castellanoz says Spanish-speaking newcomers still face some mistrust and discrimination.

|

| Don Pepe taco truck owner Jose Cuna Vera |

In Ontario, Mayor Cammack says the Latino and non-Latino residents remain divided. The town’s more established residents aren’t widely aware of the extent to which Latino newcomers have propped up the local economy and tax base. At the same time, he says, people in the Latino community haven’t opened up to the broader community, for instance, by taking part in community affairs or trying to attract non-Latinos to their businesses. “They cater to the Latino population,” he says.

In Cornelius, a farm town about 25 miles east of Portland, officials have launched a variety of efforts to integrate Latinos into the community, including Spanish-language town hall meetings, public library books and materials tailored for Latinos, and outreach to invite Latinos to volunteer as leaders on city boards and commissions.

“We feel it is important to have public positions more accurately reflect the population that we serve,” says city councilman Jose Orozco. The Latino population of Cornelius pushed past 50% in 2010, up from 37% in 2000.

In the years ahead, rural areas may not be able to rely on immigrants to stop population declines. The Great Recession triggered a dramatic end to the flow of workers from Latin America. The number of undocumented immigrants living in the U.S. peaked at 12.2 million in 2007, then fell by about a million people during the recession and shows no sign of rising, the Pew Research Center reported in September. With Mexico’s maturing economy, growing middle class and increasing employment prospects, ambitious young people feel less of a pull to go North, and many who tried working in the U.S. have returned home to stay for good.