Offshoring jobs has created anxiety among labor, as well as tensions between businesses and unions.

In 2016 U.S. presidential candidate Hillary Clinton said to a town hall audience in Columbus, Ohio, that the solution to losing jobs overseas was retraining. U.S. laborers, she argued, could not compete with workers in other countries able to accept a fraction of the wages.

The statement was seen as a gaffe by some. Her opponent went on to win the election on the promise of restoring American manufacturing jobs with strong protectionist measures and slashing environmental regulations.

The plan failed. During Donald Trump’s presidency, before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the United States lost 18,000 factories and 700,000 manufacturing jobs, according to the Economic Policy Institute, continuing a precipitous decline since 2001, which saw 3.7 million lost jobs in total.

The global supply chain sank its teeth into the snacking industry this August. Cookie company Nabisco laid off 1,000 employees, half its unionized workforce, and shut down plants in Atlanta, and New Jersey while hiring workers at its new plants in Mexico. On August 16, workers at the Nabisco bakery in Portland went on strike against Mondelēz International, Nabisco’s parent company.

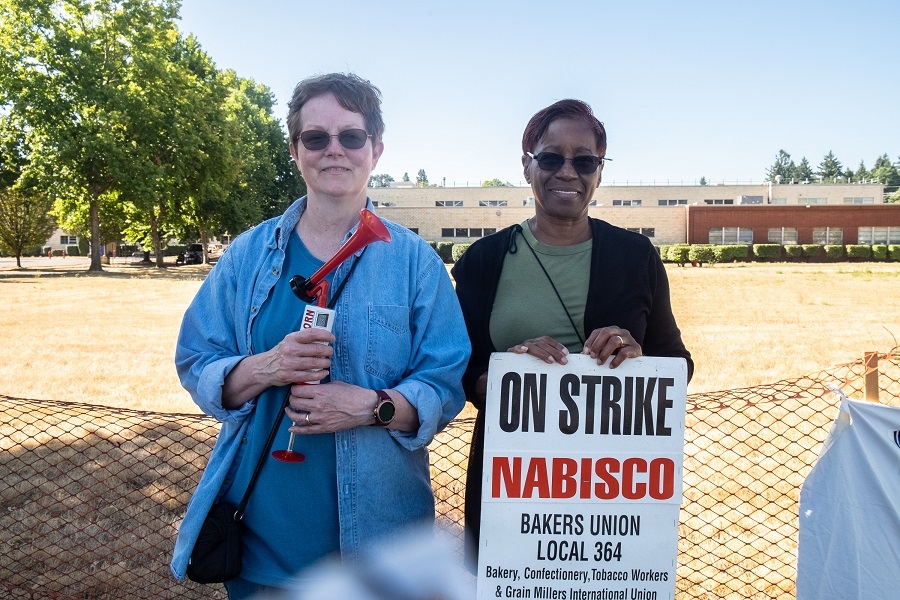

Union members line Columbia ave where they are currently undergoing a contract dispute.

Photo: Jason Kaplan

The strike was quickly taken up by the other American Nabisco factories in Chicago and Richmond, Va., and permeated a distribution center in Aurora, Colo. The dispute was born from disagreements regarding employees’ new labor contracts, which expired this year. When the pandemic hit in 2020, the union signed a one-year extension agreement, which came with a wage increase.

Cameron Taylor, business agent of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers union (BCTGM) Local 364, which organized the strike, said workers were “not thrilled” with the short-term contract but accepted it temporarily so workers at the Atlanta and New Jersey facilities, which were slated to be shut down, would have their severance based on a higher wage.

The new contract offered by Nabisco has come under heavy criticism by members. Employees cited 12-hour workdays, changes to overtime pay and the dismantling of the company’s pension plan in favor of a market-based 401(k) as reasons for the strike.

Khameron Salith has worked at Nabisco 20 years. “We just want a fair contract,” he says.

Khameron Salith has worked at Nabisco 20 years. “We just want a fair contract,” he says.

Photo: Jason Kaplan

“Members were really the boiling point with this company,” says Taylor, who explains that members’ frustration with the proposed agreement is underscored by a constant, more existential fear.

“When I started as a baker in ’83, there were 11 bakeries in the United States, and I’ve watched them drop one by one. All the union plants are dropping. In Mexico they can pay workers starvation wages, and someone who did my job organizing workers in Mexico would probably get killed,” Taylor says.

Laurie Guzzinati, senior director of corporate and government affairs for Mondelēz North America, says Nabisco’s presence in Mexico is the result of the company’s global strategy, and that the closures of the New Jersey and Georgia facilities came about because the factories were too antiquated to continue running.

“We see our future in the U.S. consisting of three strategic sites: one on the East Coast, one in the center and one on the West Coast. We see those three sites and the employees at those three sites as part of our company’s future,” says Guzzinati. “These changes are about technological advancements and driving our global ambitions with robust U.S. biscuit manufacturing. We want to be snack leaders not only in the U.S. but around the world.”

Typically, Oregon gets the long end of the stick on international trade. Oregon is the only state to have a trade surplus with China. One in five jobs in Oregon is a direct result of international trade, according to a report by the Portland Business Alliance.

But when it comes to manufacturing, Oregon workers are caught between increasing robotics at stateside facilities and cheap labor outside of the United States.

RELATED STORY: The Oregon-China Relationship Becomes Essential

The strike has been supported by Oregon Democratic legislators in droves, including state Sen. Lew Frederick, who represents Oregon’s District 22, where the Nabisco plant resides. The caucus was joined by Sens. Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, Rep. Earl Blumenauer, and Speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives Tina Kotek.

The strike has garnered national attention. Actor Danny DeVito publicly tweeted his support for the strike.

On September 2, Mondelēz publicly put forward a new contract offer, which was not accepted, and expired September 7. Given the current labor shortage in Oregon and across the country, it is likely labor has the upper hand in these dealings. Taylor says the labor shortage “didn’t hurt” when it came to bargaining.

But if and when the parties reach agreement, the landscape of manufacturing will continue its changing course. Global supply chains and technological advancements will make being a factory worker a much different experience than in the past.

Even as unions secure better agreements, automation will mean fewer factory workers will be needed, and factories themselves will need to be more spread out to secure a global market.

There are bright spots in the data, however. According to a 2019 report from the Brookings Institution, automation in factories has the potential to create more jobs than it loses.

By giving proper training opportunities, strengthening unemployment insurance, reducing tax subsidies for companies replacing labor with capital, and incentivizing technologies that combined labor and robotics, manufacturing jobs could adapt and survive the changing economy. For that to happen, labor unions will need to help shape public policy.

Jobs lost to trade deficits will be sweeping, and perhaps inevitable. The issue will only intensify as time goes on, and the solution will not be simple, despite what more coaxing politicians might claim.

While it might not win many votes, a realistic approach may be the best course of action.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.