Product makers find new purpose making equipment to combat the pandemic.

Alan Dietrich could talk all day about the ins and outs of making and selling liquor, such as vodka, gin or whiskey. It is his job, after all, as CEO of Crater Lake Spirits, a distillery in Tumalo.

But it was quite the learning curve for him when his company entered a new market last month making a product he previously knew little about: hand sanitizer.

The manufacturing switch is the result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in a shortage of the hygiene product, as well as other protective gear for health care workers, such as rubber gloves and face masks.

The World Health Organization estimates 89 million medical masks are required for the COVID-19 response globally each month. For examination gloves, the figure is 76 million. Supplies can take months to deliver and market manipulation is widespread, with stocks frequently sold the highest bidder, according to the organization.

Distilleries are uniquely placed to make hand sanitizer because they are used to making alcohol-based products. The main ingredient in hand sanitizer is ethanol. Dietrich says it was relatively easy to get production up and running by following a recipe for hand sanitizer. Official bodies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization, produce guidelines on the ingredients.

Despite the relative ease of making hand sanitizer, the switch was not something Dietrich says he even remotely imagined his company would do. “This pandemic is forcing real changes,” he says.

Most distilleries in Oregon are making hand sanitizer to meet the increased demand. Rogue Ales & Spirits in Newport has produced 260 gallons so far. “As a distillery, we make alcohol every day, so a hand sanitizer was an obvious way to help,” says Brian Pribyl, head distiller of Rogue Ales & Spirits.

Distilleries are not making a profit from hand sanitizer. The product is shipped to the Oregon Health Authority, which covers the hard costs of production and distributes the product to hospitals and health centers.

But production of hand sanitizer has allowed Crater Lake Spirits to retain some staff. The distillery has had to lay off about a dozen employees because of the pandemic response. The company has lost business from the closure of bars and restaurants, where it used to sell liquor.

It still sells a lot of its products to liquor stores, which are still open in Oregon, although sales to stores outside of that state have shut down, says Dietrich.

Making hand sanitizer has not been without its challenges. The hardest part is dealing with shortages of ingredients and equipment. Dietrich says it was difficult to procure the gel that goes into hand sanitizer. He also has found it hard to find packaging, which is traditionally made in China. That country’s manufacturing has been delayed by its own struggle to deal with the pandemic.

To address the challenges of procuring materials, the Oregon Liquor Control Commission, which regulates the alcohol sector, launched a program that allows distilleries to pool resources, such as chemicals and plastic bottles, so that distilleries can produce the product more efficiently.

The commission’s creation of the program “is the most community-based, selfless act that government has taken,” says Dietrich. “They shoulder all the coordination. Industry could not have done this on its own.”

It is not just distilleries that are heeding the call to help fight the pandemic. Other manufacturers have converted their production lines to make personal protective equipment for health care workers.

Sailworks, a Hood River manufacturer of windsurfing equipment, is one such company. Production of the business’s core product ground to a halt after its supplier in China had to shut down as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. The activity of windsurfing has also stopped in Oregon because of the closure of parks that provide access to the Columbia River, where people go surfing.

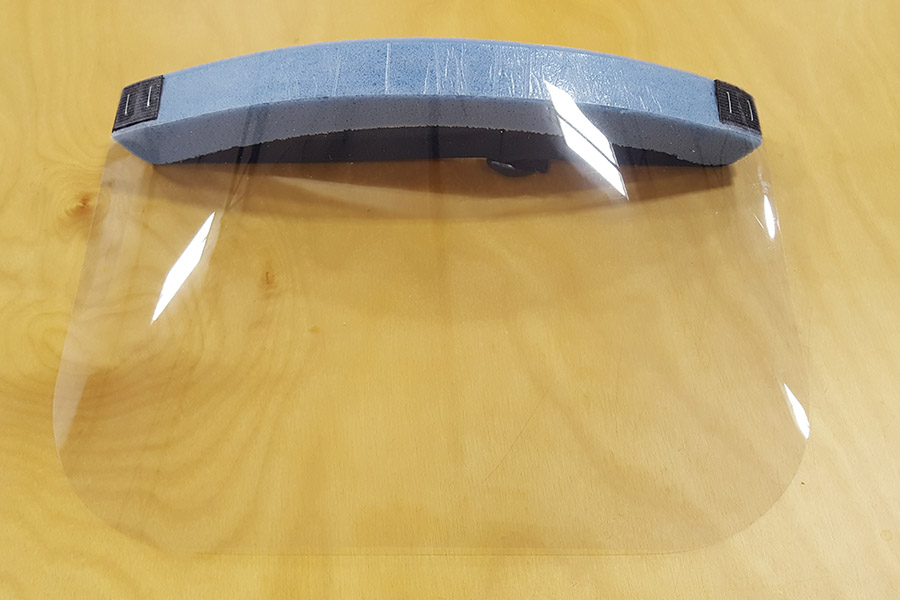

Bruce Peterson, owner of Sailworks, is kept busy, however, making another type of product: face shields for health care workers. Peterson became aware of the need for personal protective equipment at medical centers and hospitals after hearing from his wife, who is a nurse, of the shortages.

Demand has soared for protective gear, but China, which traditionally makes these products, has not been able to keep up with demand because of disruption to its own manufacturing.

A couple of weeks ago, local health care facilities put out a plea for thousands of face masks and face shields. Peterson got a hold of a specification for a face shield and found that it uses the same plastic material Sailworks includes in windsurfing sails.

Sailworks face shield

Sailworks face shield

The company got to work making samples and prototypes that it sent to local hospitals. Peterson says he wanted to make sure the face shield was a product that health workers could use. The response was overwhelmingly positive.

“It is natural for us to do this. We do a lot of testing and evaluation. We did a lot of work on elastic and textiles. We presented it to health care workers to see if they could use the product, and they said, ‘Yes, how many can we have?’”

Sailworks is on track to make 6,000 face shields, which are then distributed to local hospitals. It is making no profit on the product. A nonprofit, Handmade Brigade, is raising funds to cover the costs that manufacturers, such as Sailworks, incur from making personal protective gear.

Despite the success of the face shields, Peterson has no plans yet to add them to the company’s product line permanently. He plans to produce the protective gear for only a short period. Larger companies can do a better job of manufacturing long term, he says.

For now, the company is relying on contracts it still has with Insitu — a Bingen, Washington, subsidiary of Boeing that makes military equipment.

But Peterson hopes the shortage of medical protective gear is a wake-up call to businesses of the vulnerability of the global supply chain. Most critical medical-care goods, such as protective gear, are made in China, where the coronavirus outbreak originated. The U.S.’s reliance on cheap medical products from overseas has put it in a precarious position when it comes to efforts to deal with its own public-health crisis.

He predicts the disruption the pandemic has caused to the global supply chain will mean businesses will bring manufacturing of certain critical goods back to the U.S. “so that this doesn’t happen again,” says Peterson.

For now, Dietrich at Crater Lake Spirits also does not foresee making hand sanitizer a permanent fixture of its manufacturing. But these are uncertain times, and the longer the pandemic shuts down business, the more likely his company may have to turn to other avenues to stay afloat.

“If hand sanitizer were to become a big growth industry, we could pivot to adding it as a product line,” he says.