Low-income and minority populations face barriers to tech transport solutions.

The mobility services revolution, a vision of shared cars coordinated with transit and other modes, is transforming the auto industry. But on this connected, shared, autonomous, electric ride toward the future, some demographics get left in the dust.

Low-income and minority communities lag behind tech-driven transportation changes. Vivian Satterfield, deputy director of the environmental justice advocacy group OPAL, discussed this gap at an event yesterday hosted by the electric vehicle nonprofit Forth Oregon.

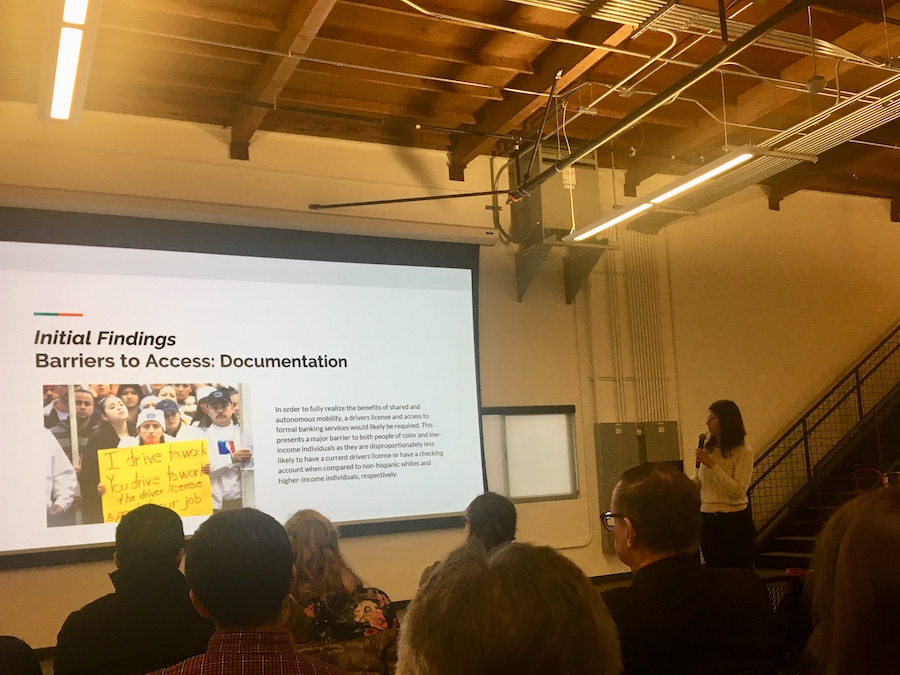

An OPAL study showed that underserved communities face four key barriers to adopting ridesharing and software-driven approaches to reforming public transit: documentation, banking, housing type and tech literacy. It goes without saying that many costly tech-transport solutions, such as Reach Now, remain out of reach for low-income commuters.

Vivian Satterfield, deputy director of OPAL, discussing the group’s study on transportation in underserved communities

Vivian Satterfield, deputy director of OPAL, discussing the group’s study on transportation in underserved communities

“These folks are not using Zipcar or Reach Now,” Satterfield says. “We assume because smartphones are so ubiquitous everyone will be able to use these apps.”

Automakers are increasingly partnering with tech disruptors and public agencies to fold private vehicles into a shared transportation ecosystem. By 2040, according to an IHS Markit Report, this emerging mobility-services sector will purchase more than 10 million cars — compared to just 300,000 in 2017.

OPAL reminds Oregonians to put on the brakes and look out the window at neglected low-income and minority populations. Some lack a driver’s license. They’re more likely to live in multifamily housing without space to charge an electric car. While many low-income people own smartphones, Satterfield said, they mainly use the basic functions— calling, text and email — not advanced transportation apps.

Part of the solution lies in updating technology. Satterfield called for offering apps in more languages, and making smartphone charging stations and wi-fi more widely available on transit.

Another speaker, Ira Dixon, program manager at the Community Cycling Center, discussed how offering electric bikes to minority groups in North Portland made their commutes easier, leading to higher wages and more working hours.

Ira Dixon talks about a community cycling center program aimed at expanding access to e-bikes.

Ira Dixon talks about a community cycling center program aimed at expanding access to e-bikes.

Yet OPAL has also issued a caveat to TriMet and other public agencies’ ready adoption of transportation technology. The group pushed back against TriMet’s decision to eliminate paper tickets. OPAL claimed the $3 cost of buying a Hop card burdens low-income riders, and that e-tickets raise concerns about privacy and “information sharing with law enforcement.”

OPAL is working with the city of Portland and public agencies to incorporate the factors identified in their study into transportation policy. But the progress has been slower than they’d like. “We’ve relayed all this stuff to a lot of people a lot of times,” Satterfield said.