BY JACOB PALMER

Ask any college student: Textbook prices have skyrocketed out of control. Online education startup Lumen Learning aims to bring them down to earth.

BY JACOB PALMER

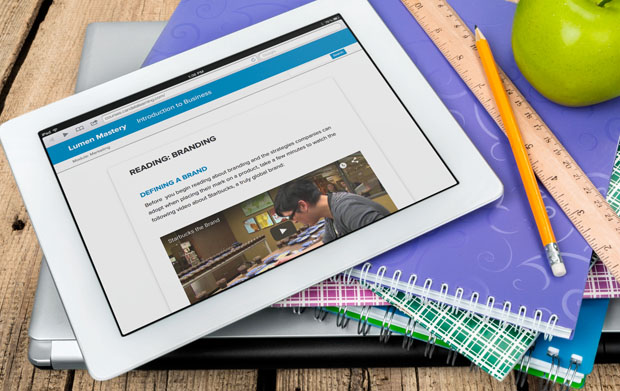

Company: Lumen Learning

Founders: Kim Thanos, David Wiley

Launch: 2012

Headquarters: Portland

Ask any college student: Textbook prices have skyrocketed out of control. Online education startup Lumen Learning aims to bring them down to earth.

The company replaces traditional college textbooks with custom packets sourced from materials with a creative commons license. “We give [faculty] a complete package, usually more than what they need,” co-founder and CEO Kim Thanos says. “They refine it to fit the curriculum, so students aren’t getting 600 pages, of which only 300 would be assigned.”

Lecture slides and assessment items are part of the instructor package. But if Lumen makes life easier for faculty, the real beneficiaries are students — especially those from low-income families. “The institutions we work with most are those that serve students who are on financial aid, or first-generation college students who have a lot of obstacles to success,” Thanos says. “It’s not unusual for students at community colleges to get through courses without a textbook either because financial aid is slow or you just don’t have the money.”

A typical college algebra book can run $100 or more. Lumen charges $5-$10 for comparable course materials. Participating institutions pay a fee to use the platform. To date, the company has signed on about 65 community colleges, including Umpqua College and the Virginia Community College System.

Lumen’s focus on democratizing educational resources has attracted attention from philanthropic organizations like the Hewlett and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundations; the latter invested $3 million and also funds many of the course materials. Thanos says. “We work with those organizations on what they’re developing, what they’re excited about and what are going to get the most use.”

Lumen has yet decide whether to conduct another funding round or grow the company organically. For now, the team is focusing on helping institutions adopt and implement the platform. ”We’re addressing the systemic changes that need to happen in education,” Thanos says. “Some things are gated in the bookstore or gated with a publisher model. We want to break that down by helping institutions move through that process.”

Back office

Lumen has 17 full-time employees and three summer interns from Epicodus, a Portland-based coding school. “It’s been nice having student eyes on it,” Thanos says. Paul Golisch, a faculty member from Maricopa Community College, helped refine the adoption process for community colleges.

Old guard

The publishing industry dismisses the Lumen model as “naive,” Thanos says. “But we don’t have to work against our customers to monetize this. We have collaborative, strategic partnerships with our institutions and that makes all the difference when you’re doing something somewhat unproven.”

Class convener

When Nate Geier, the founder of Coursetto, a corporate training platform, started the PDXedTech Meetup in 2014, he hoped to grow his network and get in on the ground floor of an emerging tech cluster. Geier estimates there are five-to-10 established EdTech companies in Portland, with another 20-25 that are close to earning funding.

Most of the companies have a common goal: simplify processes and reduce costs. “The web is moving toward customization, empowering people and democratized education,” Geier says. “That’s allowing people to take a preexisting good idea and make it easy to use.”

No single market dominates, but higher education is a prime target of the emerging sector. “Schools are going to start realizing how obsolete they can become if they don’t innovate,” says Geier. “EdTech can replace colleges. It’s a huge awakening that’ll happen in the next five-to 10 years.”

Building a professional network is key to moving technological innovation forward, Geier adds. “Not making connections was one of the biggest mistakes I’ve made. I spent over a year building contacts and talking to people and doing my own conferences.” Close to 100 people attended the most recent EdTech gathering, he says.

Of course, collaboration has its drawbacks. If the Oregon Angel Fund selects a company with a similar product, “it gets very tough, because this is still a small town,” Geier says.

{jcomments on}