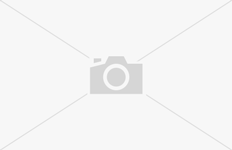

Oregon’s historically timber-dependent communities struggle to diversify with increasing desperation. What’s ahead for these once-prosperous towns? It’s a question far from answered.

Oregon’s historically timber-dependent communities struggle to diversify with increasing desperation. What’s ahead for these once-prosperous towns? It’s a question far from answered.

Oregon’s historically timber-dependent communities struggle to diversify with increasing desperation. What’s ahead for these once-prosperous towns? It’s a question far from answered.

STORY BY BEN JACKLET // PHOTOS BY FRANK MILLER AND BEN JACKLET

|

Oakridge city administrator Gordon Zimmerman is searching for an industry to fill the gap left by the closure of the Pope and Talbot mill. |

| {artsexylightbox singleImage=”images/stories/articles/archive/nov2009/screenshowintro.jpg” path=”images/stories/articles/archive/nov2009/timberslideshow”}{/artsexylightbox} |

Back when the mill was humming day and night and the hills were alive with the sound of chainsaws, visitors entered the town of Oakridge by passing a large sign that welcomed them to the “Heart of the Timberland Empire” and declared, “We owe our existence to the timber of this land.”

Oakridge still exists, but its timber industry is history. For more than a decade, it has been a company town without a company. The Pope and Talbot lumber mill closed in the 1980s. The smaller mill that took its place closed in the ’90s. The city bought the mill site in 1999, tore down the old buildings and set to work trying to re-create a local economy. A deal involving a Nevada investor promising 16 businesses and 545 jobs vanished in the muck of the recession. Few locals speak of it these days without rolling their eyes.

“We are a distressed and very poor community,” says city administrator Gordon Zimmerman as he pauses to consider the challenge he has inherited at the old mill site. “We are doing the very best we can with what we’ve got.”

Surrounded by lush publicly owned forests no longer open to logging, Oakridge and Zimmerman are laboring to make a difficult transition from timber town into something else. Their predicament is a familiar one for once-mighty Oregon timber towns from Coos Bay to Wallowa. The surroundings are beautiful, the land is cheap, the community is hungry for jobs, and a small but energetic cadre of entrepreneurs is making plans for rebirth. A lot is in the works. But very little is happening with employment. Even the most nostalgic old-timers are coming to grips with the reality that the Timberland Empire is history.

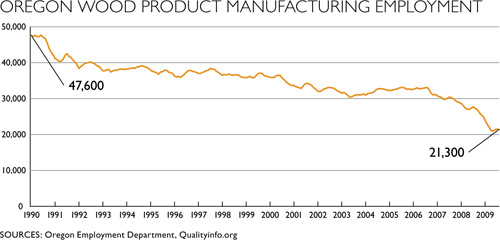

So what’s next? It’s a question that remains far from answered in Oakridge and other timber towns. Oregon is the largest lumber producer in the nation, but that is not the grand title it once was. Between the steep reduction in logging on national lands and the dramatic collapse of the housing market, employment in the wood products industry has dwindled to less than half of what it was 20 years ago. Not so long ago, timber represented more than 50% of the state’s economy. Today that figure is under 12% and falling, and the number of mill towns that no longer have mills continues to grow. These towns are left with an unenviable choice: diversify or die. Only how?

The reinvention of cities such as Newport, Hood River, Astoria and Bend show that it is possible to build on a historic base of natural resources and develop a complex, dynamic local economy. But it’s an epic challenge. As Zimmerman travels past the abandoned mill, through the poverty-stricken lowlands and up to the partially completed hillside homes near the golf course built for timber executives, the obstacles facing him and his town are unveiled in harsh succession: no rail access at the industrial park, lingering pollution at the mill, stimulus dollars that have been slow to flow to forgotten small towns, an in-migration of welfare recipients, an out-migration of families with children, absentee landlords, sprawling vacancies, an aging population, soaring joblessness. Not to mention the worst economy since the Great Depression.

During their glory days, Oakridge and neighboring West Fir were prosperous mill towns completely surrounded by Douglas fir trees that the U.S. government inventoried and sold by the board foot. The companies that ran the mills, Pope and Talbot in Oakridge and Hines Lumber in West Fir, dominated the economy to the point where they printed their own money. Employees were allowed to spend company money at the company store, a dubious practice balanced by there being plenty of money for all. Gypo loggers sawed up mini-empires in the woods; logging trucks thundered through a labyrinth of roads; and national forest employees were in constant symbiotic motion, building and repairing roads and cleaning up after each harvest by burning and replanting thousands of acres each year.

“It was a classic Sometimes a Great Notion town,” says Ben Beamer, who grew up in Oakridge and is part owner of Brewers Local Union 180, a promising local pub that he helped remodel. “Nobody wants those days back. Having one big industry running the show doesn’t work. Lesson learned.”

|

Craft brewer Ted Sobel, owner of Brewers Union Local 180, is one of a handful of entrepreneurs attempting to reinvent Oakridge’s mostly vacant downtown core. |

As part-owner of one of Oakridge’s few growing businesses and a sweat equity investor in others, Beamer is working with a small group of entrepreneurs to redefine Oakridge as a destination for trail biking and great beer, a place where the forest is an economic asset to be preserved, rather than converted into wood products. He has traveled to Washington, D.C., and Las Vegas with Oakridge-West Fir Chamber of Commerce executive director Randy Dreiling to promote Oakridge as a mountain-biking Mecca, with the hope that biking will one day do for Oakridge what windsurfing has done for Hood River.

The fact that Dreiling, the chamber director, is a hard-riding trail dude who conducts interviews at the pub and is unlikely to be seen in a suit is an indication that Oakridge is taking its push for diversity through beer and bikes seriously. It’s a vision that resonates with Zimmerman, a small-city veteran who worked in Nyssa, Vernonia and Baker City before taking over at Oakridge. “The trails will always be there,” he says as he steers his way around the new lots above town waiting for buyers. “That’s our resource now.”

At one point Zimmerman pauses in front of a partially completed home and gestures at the forest in the distance as if in disbelief. “Look at that view!” he says. “That is never going away! It’s national forest! There are spotted owls over there!”

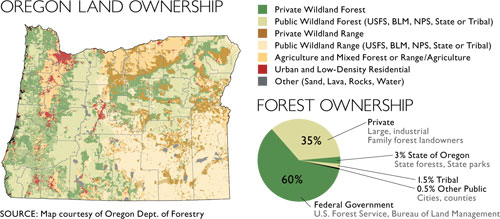

When a city administrator in a timber town celebrates spotted owls, you know the tide has turned. The spotted owl’s designation as an endangered species enabled a flood of lawsuits from environmental groups that eventually brought an end to the high-volume logging of national forests and created rural/urban divisions that fester to this day. Bob Ragon, executive director of Douglas Timber Operators, estimates that Oregon and Washington have lost 35,000 jobs over the past two decades. Ragon’s clients have been among the hardest hit, because 63% of Douglas County is publicly owned forestland.

|

Oakridge-West Fir Chamber of Commerce executive director Randy Dreiling believes mountain biking can do for Oakridge what wind surfing has done for Hood River. |

There is no disputing the role federal forest policy has played in the demise of Oregon’s timber towns. But the real problem the timber industry faces in the contemporary economy has to do with demand, not supply. For a few years, as the housing boom reached its peak and developers cranked out speculative subdivisions in California, Arizona and Nevada, timber titans such as Weyerhaeuser, Hampton Affiliates and Roseburg Forest Products appeared to be bouncing back, employing fewer people due to automation but still achieving sizable profits. Then the bubble burst. Lumber prices have collapsed as housing starts have plummeted. The industry faces a massive over-capacity problem that federal logging would only worsen.

Ragon estimates that the industry is operating at about 60% of capacity while awaiting prices healthy enough to justify revving up production. “Everybody has run into the same wall together,” says Ragon. “There was no way to escape it.”

Roseburg, the largest city in Douglas County, has never been a one-company town. At its competitive peak, this tree-filled county was home to 278 lumber mills. Most of those have faded into history, but several dozen remain, and with the diversification of the economies of Eugene and metro Portland, Roseburg has emerged as the manufacturing center of the state’s timber industry. “Timber is the dominant employer here and most likely always will be,” says Debbie Fromdahl, executive director of the Roseburg Area Chamber of Commerce.

But the industry has never been weaker. As a result, Douglas County is struggling with the highest unemployment rate in Oregon west of the Cascades.

Allyn Ford, CEO of Roseburg Forest Products, Douglas County’s largest employer and one of Oregon’s biggest private companies, doesn’t expect improvement for at least a year. “We are an industry that is built for 2 million housing starts and here we are at 500,000 or 600,000,” he says. “There is so much capacity that any time you get a little jump in the market, everybody just piles on. We’re all desperately trying to create cash. And the people who are left in the game are pretty tough people. So it’s tough out there.”

Smaller companies such as 55-employee Nordic Veneer, the sole operating mill on the North Umpqua Highway east of Roseburg, are also struggling. Owner and general manager Art Adams retooled the mill 15 years ago to adapt to the loss of old-growth timber from public lands, and he figures he’s surviving the downturn on grit and the quality of his team. “There’s an element of sweat in this work, but you also have to be smart,” he says. “You need really smart people, and that’s what we’ve got. My guys are mechanical, they’re computer guys, they know how to design things, how to fix things. Most of them can do two or three jobs. That’s how we’ve been able to survive.”

|

Debbie Fromdahl, executive director of the Roseburg Area Chamber of Commerce, is working with other local officials to diversify Douglas County’s economy. Still, she believes timber will always be the dominant local employer. |

Others have not been so fortunate. The collapse of the market has devastated not only mills and mill towns but also ancillary businesses that rely on wood products. “The whole infrastructure is impacted,” says Ford. “You look at the people doing the logging and the trucking and the service industry that supports all of that and it’s all down. We normally do quite a bit of construction around here. We’re always renovating and tearing down things and building things. That’s all come to a stop.”

Unlike Oakridge, Roseburg has made significant strides to diversify its industrial base. It is a much larger city, centrally located on I-5, with quality industrial land and an active community college offering workforce training. Ironically, Roseburg’s attempts at diversification have not held up any better than has the timber industry. For a while the town hosted a robust boat-manufacturing cluster featuring a Bayliner plant and a homegrown company called North River that claimed to be the fastest-growing aluminum boat builder in the nation. But the Bayliner plant has shut down and North River has suffered from a series of scandals that culminated with the September arrest of owner Brian Brush for allegedly killing his ex-girlfriend.

Roseburg and Douglas County also went to great lengths to lure a Dell call center to town, only to have the computer giant close up shop in favor of cheap labor overseas in a manner that inspires resentment to this day. On the morning of a morale-raising “wear your pajamas to work” day, employees showed up ready for a work party to find the front doors locked and the operation apparently shut down. Terry Swaggerty, who served as Umpqua Community College’s Dell recruiter, remembers that morning vividly. “We did back somersaults for Dell,” he says. “For them to turn and bolt on us the way they did, it just left a bad taste in a lot of people’s mouths.”

Most of the economic success stories of Douglas County have been locally generated, such as Umpqua Dairy, the sewage system developer Orenco and the growing empire of the Cow Creek Tribe, which runs a casino and a dozen other businesses and employs about 1,500, more people than it has members. The VA hospital is a steady employer that won’t be going away, as is Mercy Hospital. The local wine industry has also held up well and is poised to expand significantly as a result of a string of major vineyard purchases and the Southern Oregon Wine Institute north of Roseburg.

|

Allyn Ford, CEO of Roseburg Forest Products, remains optimistic about the long-term forecast for Oregon’s timber industry: “We’ve got the wood, we’ve got the technology, and we’ve got access to the biggest market in the world.” |

The combination of wine production and upscale tourism has worked wonders in the Willamette Valley, but the Umpqua Valley is far from competing for those visitors. Local wineries do not offer overnight lodging, and gourmet food is the exception rather than the rule. One of the reasons people have been buying up land for wine cultivation is real estate is cheap. The countryside is gorgeous but there is no destination resort other than a tribal casino and a safari game park. And the area is littered with large vacant properties that serve as lumbering reminders of the downfall of the industry that fueled the town through better times.

Helga Conrad, director of the Partnership for Economic Development in Douglas County for 10 years, says it has been a challenge to find replacements for the highly paid union jobs people enjoyed while the mills were thriving. Among the missing attributes she wishes she had to market are a four-year university, a commercial airport, and a rail connection to the Port of Coos Bay.

Given the mixed results in areas outside of wood products, timber executives argue that Douglas County, and the state of Oregon for that matter, should embrace the industry upon which they were built.

“Our industry is very dynamic and very solid,” says Ford. “There has been some drop in employment and some drop in supply, but the demand for wood products is still there. Oregon is still No. 1 in lumber, plywood and all wood products in the United States. And from a technology standpoint we are world class. You walk into our mills, you’re walking into lasers, computers. We’ve got robots in our plywood plants now. I know the image is that it’s an old, dying industry. It’s not. Yeah, it’s been around for a while. But it’s not dying.”

|

Nordic Veneer owner Art Adams says he’s surviving the industry’s slump on the ingenuity of his 55 employees. |

It frustrates Ford and other industry leaders that state leaders put so much emphasis on solar and wind energy, when Oregon would seem to have a strong advantage in producing renewable energy from woody biomass. Another source of continual angst for the industry involves federal timber policy, which appeared poised for change under the Bush Administration only to stall out under President Obama. Timber supporters make the case that a combination of fire prevention, increased harvest and biomass development (in addition to carbon credits for planting trees) could restore Oregon’s forests as well as its economy.

“You look around this county and you’ll see a lot of 50- to 60-year-old Douglas fir, which happens to be one of the best building materials in the world,” says Ragon. “We have been on the top of the competitive heap of that market for 20 years and we want to stay there. If our national forests were managed properly, the job losses would end and new mills would get built. But people need certainty to invest.”

It remains to be seen whether federal forest policy will change, and if so, how. Another question involves how well a return to intensive logging on public lands would mesh with simultaneous efforts to develop an upscale wine tourism industry. Not every business benefits from clear cuts and roads rumbling with logging trucks. Worth pointing out is that of the many vocational courses at Umpqua Community College, one of the least popular involved preparing students for jobs in the timber industry. It was offered for several semesters but was eventually canceled due to lack of interest.

Some 220 miles to the northeast, in Prineville, the landscape is different but the percentage of publicly owned forestland is similar. Unlike Oakridge and Roseburg, Prineville was not built on Douglas fir. It was built on ponderosa pine. The city’s founding fathers developed a short line connecting the town with the main railroad line through Central Oregon, and before long rail cars crammed full of pine lumber were pouring out of Crook County. The deal was so lucrative that the railroad paid for all city services and built the county its first courthouse.

A generation ago five large mills cranked out lumber in Prineville and logging was a common, high-paying job. Today logging has all but ended and the two mills that remain in Prineville are secondary job shops that have had to change radically to survive.

|

Bob Horton of Contact Industries with one of the specialty wood and aluminum products manufactured in Prineville. |

Bob Horton, vice president of manufacturing for Contact Industries, which is headquartered in Clackamas County but does its manufacturing in Prineville, says his company would not exist at all if it hadn’t moved from making commodity wood products to filling custom orders. “What we did was we leveraged our understanding of both wood technology and adhesive technology to redefine our product line,” he says. “At one time we were 90% commodities and 10% specialties. Now we have reversed that. We’re probably 95% specialties now.”

Much of Contact’s business involves slicing high-quality wood very thinly and wrapping it around cheaper wood and also aluminum, to solve specific problems for architects on a job-by-job basis. “We’re the only people on the face of this earth that measure aluminum products in board feet,” says Horton. “You can fight the commodities or find a niche. You can listen to the green movement or you can ignore it. We listened.”

That strategy has enabled Contact to survive. But the local economy of logging, trucking, milling and distribution is gone. The railroad tracks that once symbolized Prineville’s connection to the outside world end abruptly in the middle of town, just short of the former Ochoco Lumber mill.

It marked the end of an era and the loss of an annual payroll of $5 million when Ochoco closed its Prineville mill in 2001. By then the company already had shifted jobs to Lithuania, where it bought a mill in 1994, and transitioned from local production to global marketing. Now Ochoco is making another transition — one that has nothing to do with timber. The company has removed more than 4,000 tons of contaminated soil from its former mill and restored the Ochoco Creek to lay the foundation for a multi-use commercial district modeled on the Old Mill District in Bend.

It’s a compelling model. After Bend’s mills closed in the early 1990s, many observers predicted economic collapse. Instead, Bend doubled its population and built a vibrant modern economy in which land values soared. The mill’s old powerhouse was converted into a Recreational Equipment Inc. store in 2005.

|

The railroad tracks that once brought prosperity to Prineville come to an abrupt halt next to the former Ochoco lumber mill. |

Bend’s mills employed 1,800 at their peak. Today the Old Mill District employs 2,750. Not all of those jobs are full time, much less union jobs, but they aren’t all low-paid service jobs either. Bend has nurtured an impressive collection of local startups in technology, outdoor equipment, and specialty foods and beverages, and while the downturn has hit the area hard, its diversity should help it to rebound powerfully.

For better or worse, Prineville is no Bend. Furthermore, the strategy of following Bend’s lead into real estate is hardly foolproof, as Prineville-based Community First Bank found out the hard way. Community First prided itself on investing 100% of its local deposits back into Central Oregon. Unfortunately, many of those investments unraveled when the housing bubble burst. Prineville’s community bank failed in August, a casualty of a crisis that has cost thousands of realtors, mortgage brokers, construction workers and subcontractors their jobs in Oregon.

Brooks Resources, which led the charge from timber to real estate speculation in Central Oregon, is also learning that which inflates can also burst. After big successes with the Old Mill District and the Black Butte Ranch destination resort, the timber spin-off has been hard-pressed to sell homes at its Iron Horse project on the butte above Prineville. The original plan called for 2,900 homes but sales have been sluggish. All three builders who invested are offering discounts.

From 2000 to 2007, Crook County was the state’s second-fastest growing county, behind only Deschutes. No more. Median home prices have dropped by about 40% over the past year in Crook County, and with a local unemployment rate hovering around 20% (the highest in Oregon), few are expecting a recovery in the local market anytime soon.

So what’s next?

Ask Jason Carr that question, and he reels off a long list of possibilities ranging from data server farms and wind power to plastics manufacturing and higher education. “We’ve got a lot in the works,” says Carr, a former television reporter who manages the Prineville office of Economic Development for Central Oregon. “Unfortunately, everything takes a lot of work here.”

Carr and other local officials are tapping public funds to build a community college campus, realign the railroad and develop a switching yard near the main line. But each new effort to diversify brings its own set of problems. New discoveries about the inadequacy of the local water supply make server farms a long shot. A wind power development is making better progress, but local jobs in that industry are few. There’s a lot of support for a biomass power plant, but the economics are not yet looking favorable.

“Economic diversification is not the sort of work where you see overnight success,” says Carr.

Harney County, which rivals Crook County for the highest unemployment rate in Oregon, is set in a mesmerizing high desert landscape of endless sagebrush, with less than one person per square mile. It seems an unlikely setting for a timberland empire, given the lack of trees. But it was the biggest timber deal in the history of the U.S. Forest Service that brought Illinois timber baron Edward Hines here in the 1920s.

Having secured a monopoly on 890 million board feet of publicly owned ponderosa pine forest north of town, the Hines Lumber Co. established the company town of Hines adjacent to Burns and built one of the largest lumber mills in the world. With an unlimited supply of trees to cut, no competition and a booming market, Hines could afford to pay good union wages in the town he named after himself.

|

Harney County Judge Steve Grasty vows to “chase everything” to revive local industry. The recent closure of an RV factory leaves Harney County with no manufacturing. |

The market stalled during the Great Depression, but it returned with vigor following World War II, and well into the ’60s, ’70s and early ’80s. When Harney County Judge Steve Grasty came to town in 1971 to work at an auto parts store, he was amazed at how much money was floating around town. He thought he was living well on $350 per month, but almost everyone he met was making 10 times that, logging in the woods north of town or working at the mill.

“I’d seen people with money before,” says Grasty. “But I’d never been in a town where everybody had money.”

In 1973, Harney County was the wealthiest county in Oregon as measured by per capita income. But more than 1,000 jobs vanished when Hines sold the mill in the early 1980s. Subsequent attempts to revive smaller iterations of the mill have been short lived, with Louisiana Pacific shutting down in the fall of 2007. Now that the RV industry has imploded and taken the local Monaco Coach plant with it, Harney County is left with 10 manufacturing jobs officially, although the true number is probably closer to zero. It also has the highest percentage of public sector jobs of any county in Oregon.

In an effort to create new jobs, Grasty and the county are purchasing the former Louisiana Pacific mill and looking for a buyer. Their plan is to hire a salvage company to clean out the old mill and recruit an established firm to restart the local wood industry through some combination of harvest, salvage, fire risk reduction, biomass and wood pellets. They also plan to use part of the property as an incubator space for promising local startup ideas from former mill workers and employees from the RV manufacturing plant that recently closed.

“We will chase everything,” he says.

Catching something won’t be easy. Bringing new jobs to a land as remote as Harney County will always be a challenge.

Fortunately for Harney County, ranching has fared better than timber. The ranching community has its own issues with public lands grazing restrictions and unpredictable prices, but it has remained strong enough to keep downtown Burns in business, humming along with a vibe that is nothing at all like a ghost town — more like a friendly little place where everyone knows everyone else.

“It’s the kind of town where you can walk anywhere you without worrying about being safe and let the kids ride their bikes free,” says Jan Oswald, owner of Gourmet and Gadgets, a kitchen supply store downtown. “No matter how things are, everybody helps everybody out.”

Fran Davis, owner of the Broadway Deli down the street, adds: “If I can buy it in Burns, I do. Every dollar that gets spent in this town comes back around.”

Certainly fewer dollars make the local rounds than in the mill’s heyday. But a steady trickle of tourists and truckers keep the wheels of commerce turning, and the annual bird migration festival grows larger each year. Locally owned shops such as Grandma’s Cedar Chest, Ribbons and Roses, Country Lane Quilts and the Tumbleweed Floral and Paper Company have managed to keep their doors open. The community emphasis on buying locally to help each other out has helped pull new shops such as Harney County Clothing and the Children’s Barn through the worst of the recession.

|

|

|

Timber industry advocates argue that thinning, woody biomass and specialty milling could boost local economies and prevent forest fires in the ponderosa pine forests east of the Cascades. |

Similar green shoots can be found in Oakridge at the Trailside Café, at the Willamette Mercantile Bike Shop, at a building being remodeled into a hostel for cyclists, and at the concerts in the park organized by Vivian Erickson, co-owner of the Oakridge Motel.

Mountain Bike Oregon sold out in August, bringing in 300 people from as far off as Miami to ride on Oakridge’s hundreds of miles of trails through the forest. Motels were booked, restaurants packed. Local beer flowed.

As the summer tourist season faded into autumn, the Oakridge city center remained plagued with vacancies. But one of the newest businesses to open is worth considering. Laura Robson originally moved to Oakridge to work for the forest service, burning and replanting harvest areas after the trees had been harvested. She loved the area and decided to stay and invest, even after the mill closed and the economy crumbled. She bought a house and sold it at a nice profit to a cyclist who was up from California to participate in Cycle Oregon. That deal gave the buyer a cheap second home with access to amazing biking, while enabling Robson to buy a new home that came with a commercial building on the main drag.

Robson has restored the building into a massage studio called Mountain Therapeutics. Business has been brisk, community support strong, and other small breakthroughs are on the way just down the street. “A lot of people thought it was the end of the world when the mill shut down,” she says. “I didn’t. They were really pissed off they were losing their jobs, and I don’t blame them. But for me, this is an opportunity. This is something I can afford to be a part of.”

After years of watching her town struggle to replace Big Timber, Robson has concluded that turning timber towns into something else takes time, work and a whole lot of small steps. It’s a lesson that applies to much of Oregon, which continues to wrestle with an unemployment rate well above the national average, particularly in rural areas and especially in timber country.

The economic forecast calls for a long, sluggish return to a downsized version of prosperity, with jobs in Oregon returning to pre-recession levels somewhere in 2013. The forecast for the wood products industry is even bleaker. Timber towns with sprawling industrial vacancies will be hard-pressed to attract major employers to their former mill sites.

Reinventing themselves as bedroom communities and tourist destinations will be challenging. These towns will need all of the public resources they can get and all of the locally grown ingenuity they can muster, whether it’s public servants such as Steve Grasty chasing everything to create a few jobs in Harney County or wily timber veterans such as Bob Horton and Allyn Ford developing new strategies to diversify the industry itself.

Perhaps most vital to the future of Oregon timber towns are the local entrepreneurs who recognize the opportunity in building something new where little currently exists, not with the goal of replacing what has been lost, but with the inherently optimistic belief that more small successes will follow, and things are bound to change for the better, with time.

“This town is pretty empty now,” says Randy Dreiling, the trail-blazing director of the Oakridge chamber. “But it was worse. And in five years it’s gonna be way better.”