Manufacturers grapple with automation.

In an industrial park on the outskirts of Portland, a small team of engineers are putting the final touches on an elaborate machine they have just built. The machine makes liners for bicycle helmets that are designed to protect against brain injury.

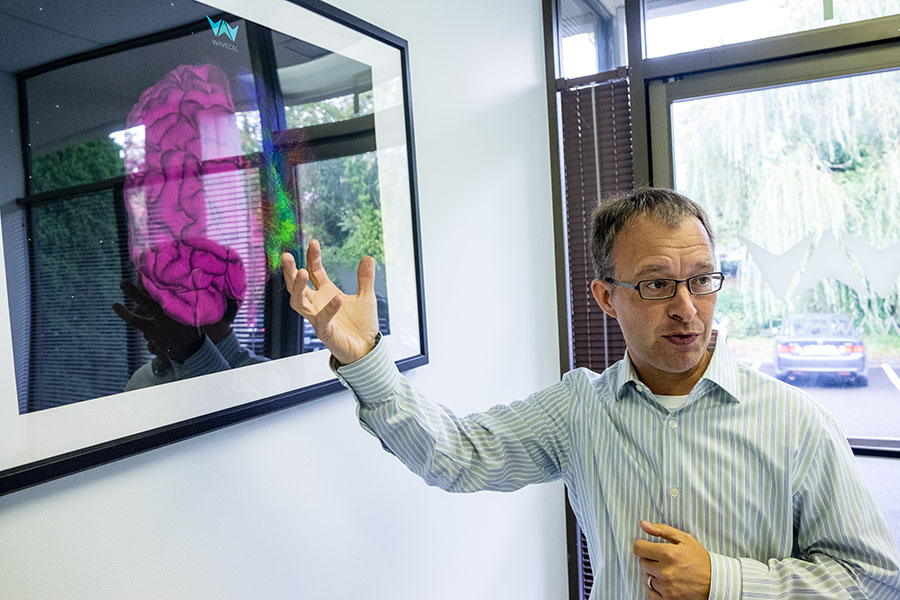

Michael Bottlang, director of the Legacy Biomechanics Laboratory in Portland, spent more than 10 years researching and developing the new product, known as WaveCel. He also helped design the new machine that will mass produce the liners.

Michael Bottlang

Michael Bottlang

Bottlang’s team is still refining and optimizing the machine, which had its first production run at the end of September. If all goes well, the bicycle-helmet manufacturer that will distribute the liners — details of which have not been released — plans to launch the new product at the Tour de France in 2018.

The liner technology is complex, featuring helmet inserts that are made of several layers of a polyester resin. The material compresses like an accordion on impact to protect the cyclist against brain injury. So precise is the technology that the makers decided to fully automate the manufacturing of the product to eliminate the risk of human error.

“This is a safety product. There is a liability risk if it is not automated,” says Bottlang. The machine requires only one or two people to operate, he says, and once production is in full swing, the startup will employ just six people per shift.

It is the new reality of manufacturing today that automation is not only increasingly pervasive, it is essential to many companies’ ability to stay in business. The rise of imported goods made in foreign countries has been a shock to U.S. manufacturers, which have to produce more volume and at a higher quality to beat the competition.

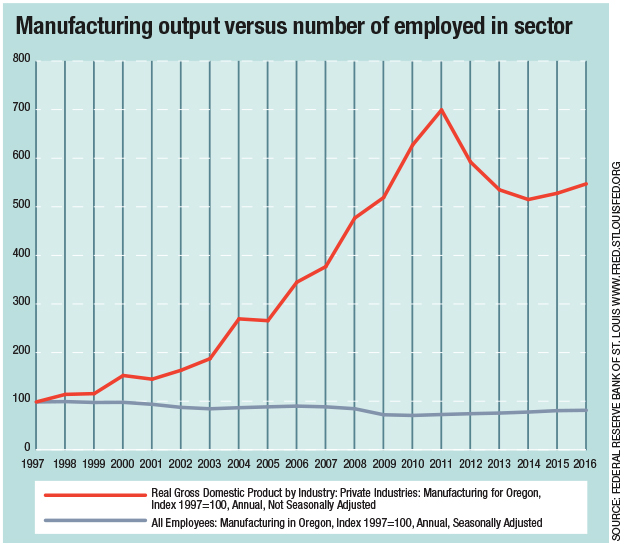

Automation is a way for many manufacturers to compete effectively in this globalized economy, and in Oregon mechanization has had a huge impact on manufacturers’ productivity. This can be seen in the sharp growth in output of goods produced in Oregon’s manufacturing sector, which has increased more than fivefold over the past two decades, according to Federal Reserve Economic data. (See chart below).

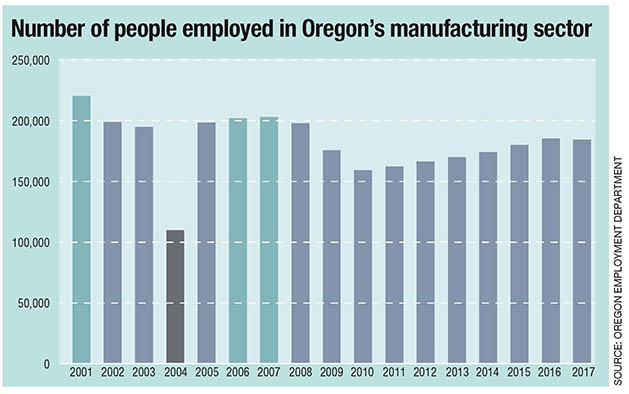

But automation brings its own challenges. The number of people working in manufacturing has steadily declined (see chart below) as machines have replaced many of the tasks that employees once did. (Automation isn’t the only factor; trade and foreign competition are also compressing the workforce.) Mechanization is also transforming the skills employees need.

An automated workplace requires workers who are skilled in engineering, software and design. Not only do these professionals demand higher salaries, they are also hard to find. Many companies struggle to employ people who have skills that are up to date with today’s advanced technologies.

Automation is particularly hard on smaller manufacturers, which are facing a crossroads on what to automate and when. “The major hurdle is cost,” says Jim Wehrs, a managing consultant for the Oregon Manufacturing Extension Partnership (OMEP), an organization that advises manufacturers on how to compete in a global economy.

Automation is particularly hard on smaller manufacturers, which are facing a crossroads on what to automate and when. “The major hurdle is cost,” says Jim Wehrs, a managing consultant for the Oregon Manufacturing Extension Partnership (OMEP), an organization that advises manufacturers on how to compete in a global economy.

The majority of Oregon manufacturers employ fewer than 19 people, and these small businesses rarely have the capital to outfit a factory with machines. Wehrs estimates only a small percentage of Oregon companies are fully automated, partly because of cost and partly because many make specialty products that do not lend themselves well to machine production.

For manufacturers of highly commoditized products, mechanization is simply a necessary step to remain in business.

“The purpose of automation is to increase productivity to stay in business. It is not to eliminate jobs. It is to keep jobs.” — Stéphane Rousseau

A newly built, fully automated tissue paper manufacturing facility in Scappoose is one such example. Cascades, a giant Canadian paper-products company, opened the 300,000-square-foot, state-of-art facility in July this year.

The $64 million factory runs 24 hours a day converting 3-ton paper rolls from its pulp mill in nearby St. Helens into tissue products. The factory houses what Stéphane Rousseau, executive vice president of primary mills and major products, calls “the fastest machine in the world” for making multifolded paper hand towels.

The sparsity of people on the huge factory floor is noticeable. In fact, just 71 people are employed over two shifts to run a factory roughly the size of five football fields. The low hum of machines fills the enormous warehouse, where a handful of employees monitor operations on the shop floor.

Cascades’ Scappoose tissue factory

Cascades’ Scappoose tissue factory

Rousseau says automation at the plant has ensured employees do not perform repetitive tasks, which he says can be a health and safety hazard. Instead, the factory’s jobs are more skills based, such as managing programmable controllers and robots, and optimizing production lines.

A large portion of the workers on the shop floor are employed to maintain the fully automated production lines. Because of the high value of the machines, it is increasingly important for factories to employ people to prevent the machines from breaking down. Even the schedule for maintaining the machines is preconfigured by a computer, which tells employees what checks they should do during the day.

Cascades’ Scappoose facility is the most automated of all its 19 tissue-making factories in Canada and the U.S. Rousseau says the 52-year-old company plans to ramp up automation at the rest of its factories to remain competitive.

Stéphane Rousseau

Stéphane Rousseau

“The lines are more productive here than anywhere else. This is what technology is all about. It is beating records and speeds of manufacturing. But it is also making quality. If you have better quality, that is a guarantee of more business,” says Rousseau.

Despite Cascades’ high level of automation, the company has increased the number of people in its tissue group rather than cut it, he says. Tissue product sales have increased to $1.2 billion, compared with $500 million 10 years ago, and the company is expanding. “The purpose of automation is to increase productivity to stay in business. It is not to eliminate jobs. It is to keep jobs,” says Rousseau.

“The more pleasant we can make the manufacturing environment, the easier it is for us to find and retain highly qualified workers.” — Jeff Allen.

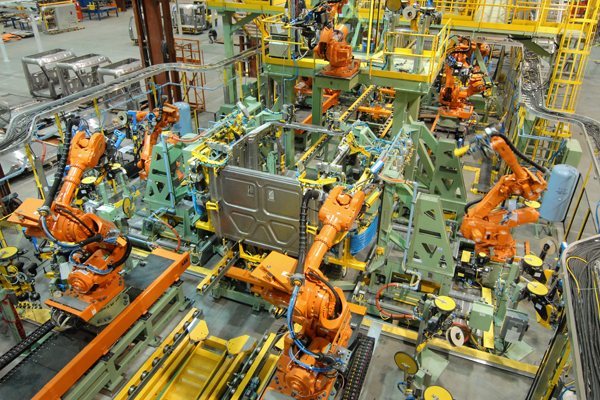

The growing complexity of its products is what drove Daimler Trucks North America to increasingly automate the manufacture of its vehicles. The process has also made it easier for the company to hire, says Jeff Allen, senior vice president of operations and specialty vehicles.

The U.S. operations of the German company, which are headquartered in Portland, have automated processes, such as paint application and welding, for the past 15 years. But just over the past couple of years the company has ramped up automation in logistics and supply-chain management, which have become more complex, Allen says.

Part of the automation of the logistics part of its business is the introduction of automatic guided vehicles on its shop floor. The self-driving vehicles, which Daimler builds in-house, move materials around the factory floor, replacing driver-operated forklift trucks. The introduction of automatic guided vehicles became necessary because the shop floor was getting too congested with manually operated vehicles for moving materials, creating a safety hazard. “We need more material and we need it delivered just in time,” says Allen. “It also made it easier to pick certain parts and get them to the point of use. A lot of it is safety but also increased complexity of product.”

Aerodynamics testing at the Daimler Trucks North America wind tunnel in Portland

Aerodynamics testing at the Daimler Trucks North America wind tunnel in Portland

To improve quality, the company also uses a machine to tell operators which part to pick out of a logistics bin to ensure the team is putting the right components on its vehicles at the right time. In the past, workers would have to sort through a stack of paper to determine which part to pick. With automation, the right part pops up on a screen or lights up in a bin to aid the operator’s decision making.

“The vehicles we are producing are much more complex, so the risk for the operator to make a mistake with automation is greatly improved. That is why we have invested heavily in this area,” says Allen.

Robotic cab assembly, Daimler Trucks North America

Robotic cab assembly, Daimler Trucks North America

Over the past 10 years, automation has improved efficiency across Daimler Trucks North America’s manufacturing facilities by 25% to 30%, estimates Allen. That in turn has helped the company become more competitive. But it has also helped Daimler save money by allowing it to bring work in-house that it used to contract out to suppliers. In the past, it was often cheaper for companies to buy machines from suppliers. Now that manufacturing has ramped up in the U.S., particularly in car manufacturing, lead times are higher, says Allen. Daimler recently started fabricating turbo chargers and transmissions, which it used to purchase from a supplier. It also builds some of its robots.

For the most part, automation is supported by the truck maker’s workforce. “The more pleasant we can make the manufacturing environment, the easier it is for us to find and retain highly qualified workers,” Allen says. “When the economy is hot, it is hard to attract people that want to work in heavy manufacturing – it has got to be an environment that is clean and safe, well lit and organized, and where the worker doesn’t go home dead tired every day.”

Jeff Allen

Jeff Allen

A lot of automation is actually driven by the workforce, says OMEP’s Wehrs. With the employment rate low and manufacturing workers in high demand, employees are picky over the work they choose. “People don’t want to do mundane tasks,” he says.

But the lack of skilled workers in many trades, particularly in machine maintenance, means manufacturers increasingly have to focus on training their staff. Valerie Johnson, owner of D.R. Johnson, a lumber company in Riddle, found she needed to hire people with skills that she never relied on before getting into the highly automated process of making engineered wood products.

Inside the D.R. Johnson mill in Riddle, Oregon

Inside the D.R. Johnson mill in Riddle, Oregon

D.R. Johnson started making these wood products, known as cross-laminated timber (CLT), two years ago. CLT, which consists of layers of wood boards glued together for extra strength, can be used to construct tall buildings. The new product is seen by many in the industry as a potential savior for the wood-products sector, which has suffered from declining sales the past few decades.

CLT lends itself well to automation because it is highly engineered and sold prefabricated. Wehrs identifies wood products as well as food processing as two sectors that are ripe for more automation in Oregon.

RELATED STORY: MORE MANUFACTURERS NEEDED TO JUMPSTART MASS TIMBER INDUSTRY

About 50% of the equipment at D.R. Johnson’s CLT manufacturing plant is automated, says Johnson. She hired a mechanical engineer who can work with architects, as well as a logistics expert who ensures the CLT products arrive to the customer in order and on time.

D.R .Johnson has another sawmill founded in 1951 that makes specialty wood products. That mill is “not as modernized” as many other sawmills, says Johnson. She wants to start to automate some of the processes in the mill eventually. “There is no getting away from automation and the people that have the skills for that,” says Johnson. “The entire industry is moving rapidly to more efficient production.”

Echoing Allen, Johnson says it can be difficult to attract young people to apply to work at her company because of the perception that the wood-products sector is manual and unstable work. “The lumber industry has modernized. We would like to get the word out to the young generation that this is not your grandpa’s work anymore,” she says.

RELATED STORY: BEAM ME UP: TALL TIMBER COMES TO OREGON

For small and midsize companies working on low margins, automation can be a daunting financial prospect. But the cost of machines is much cheaper than what it used to be. Many components, such as cameras and motors, can be bought from a catalog, says Wehrs.

Ninety percent of parts that the makers of the WaveCel bicycle helmet safety technology put into building their machine came off the shelf. Companies find that it can be much cheaper to build their own machines in-house given that many parts are now modular.

“We tried to minimize the custom-made parts, which are a lot more expensive and time consuming,” says Stanley Tsai, an engineer who helped design and build the machine. The minimal human involvement in the actual manufacture of the liners limits the company’s liability from human-caused defects.

Stanley Tsai describes the workings of the WaveCel production machine

Stanley Tsai describes the workings of the WaveCel production machine

The decline in cost is a game changer for smaller companies with limited budgets. Wehrs, who helped guide the bicycle helmet manufacturing team through the automation process, says one of his clients spent $75,000 on its first machine a few years ago. The company then went on to design and build their own machine for $35,000. It is not only cheaper but also nine times more productive, he says.

Automation is now a no-brainer for startup manufacturers that are not making highly customized products. “The last two companies I worked with were both startups with zero revenue. They wanted automation from day one. They saw growth that way,” says Wehrs.

Despite clear advantages, automation also takes long-term investment and up-front capital costs that some manufacturers may struggle with.

A new manufacturing R&D and workforce training center is just the kind of facility that helps smaller manufacturers navigate mechanization.

The Oregon Manufacturing Innovation Center (OMIC), an R&D and workforce training center launched in January this year, is a collaboration of private-sector companies — including The Boeing Company and Mitsubishi Materials Corporation — and academic institutions Oregon State University, Portland State University, Oregon Institute of Technology and Portland Community College.

RELATED STORY: BOEING PITCHES COLLABORATIVE R&D MODEL

OMIC is a place where smaller companies can test out equipment they would not usually have access to. The workforce training center, led by Portland Community College, offers employee-sponsored apprenticeships that aim to prepare young people for working in highly technical manufacturing facilities.

The new center has been valuable to Daimler Trucks North America, which is collaborating with OMIC on figuring out ways to bring project-development times down. The partnership has helped the truck maker find ways to reduce the time it takes to create tools used in the manufacturing process. “Some of the work we are doing with OMIC allows us to reduce the lead times by up to 70% and tooling costs by up to 50%,” says Allen.

These efficiencies do raise concerns. Mechanization is reshaping every aspect of our daily lives, from self-driving cars to warehouses operated entirely by robots. And in some ways, companies like WaveCel embody our worst fears, inasmuch as its manufacturing process requires virtually no human workers.

But done right, automation can vastly improve productivity, enabling manufacturers to grow and employ more people. In many cases, manufacturers must either adapt to become more efficient or face closure because of competitors that have harnessed technology more effectively. WaveCel liners would not exist without automation, Bottlang says.

“With partial automation, we likely would need to source manufacturing to China due to labor costs, since easily more than 10 full-time workers would be required. With our high level of automation, we retain production in Oregon, while creating several full-time jobs for skilled labor.”

Mechanization does require purposeful investment in workforce training and technical, skills-based education, and these are areas Oregon and the rest of the U.S. have seriously neglected. OMIC is a step in the right direction toward shoring up the skills gap, but the shortage of qualified workers persists and will continue to persist without intentional, long-term investment.

Many manufacturers realize this and are pushing full steam ahead with investments in technologies and new approaches to workforce training. As Cascades’ Rousseau puts it, automation is essential to growth and its ability to retain staff: “To stay in business, you have no choice but to remain competitive. The way we do it is not automating by eliminating jobs; it is automating by increasing capacity and creating jobs.”