Share this article! Apparel giant Columbia Sportswear was recently awarded $3 million in a lawsuit the company filed against Seirus Innovative Accessories for infringing a patent on its Omni-Heat technology. Most news articles have centered on the financial rewards for Columbia. A lesser known story is how this case sets precedent for U.S. patent law. … Read more

Apparel giant Columbia Sportswear was recently awarded $3 million in a lawsuit the company filed against Seirus Innovative Accessories for infringing a patent on its Omni-Heat technology. Most news articles have centered on the financial rewards for Columbia. A lesser known story is how this case sets precedent for U.S. patent law.

When a company proves that a competitor has infringed one of its patents, a debate ensues over how much in damages the infringing company should have to pay. The Columbia v. Seirus decision could have implications for similar discussions down the road.

We talked to Nika Aldrich, the lawyer who argued on behalf of Columbia, about the case and how it will guide future patent law decisions.

The infringing Seirus Heat Wave design / Screenshot from Columbia complaint

The infringing Seirus Heat Wave design / Screenshot from Columbia complaint

The Columbia trial, Aldrich said, was one of the first cases addressing a precedent established in the Supreme Court case Samsung v. Apple. In that case, Samsung was found guilty of copying the design of Apple’s smartphone screens.

The court ruled that it could be too draconian for Samsung to pay all of the profits it made from the infringing phone (the “article of manufacture”). The case was sent back to a lower court to decide whether the company had to pay total profits from the sales of the phone, or only the profits from the offending components.

“In the case of a multicomponent product,” the unanimous court decision read, “the relevant ‘article of manufacture’ for arriving at a §289 damages award need not be the end product sold to the consumer but may be only a component of that product.”

But the decision created some wiggle room. The court ruled that in some cases a company might have to hand over profits from the entire product. When exactly that needed to happen was left to juries to decide. And a jury never had to make that call until now—Columbia v. Seirus.

“Somebody had to come up with a legal rule since the Supreme Court decided not to,” Aldrich said.

For Seirus this meant that a jury could decide whether the company would pay only a few hundred thousand dollars in the cost of the Heat Wave fabric in the gloves, or more than $3 million for profits from sales of the gloves as a whole. Seirus tried to cite Samsung as precedent—and failed.

As with backroom deliberations in a murder trial, nobody really knew what jury members were thinking. Maybe they defined the “article of manufacture” as the entire glove. Or they defined it as just a component, the Heat Wave fabric, but decided the profits from that fabric equated to profits from the entire gloves, possibly because Seirus advertisements prominently featured Heat Wave fabric when selling the gloves. Aldrich put forward several arguments, but it’s unclear which one the jury picked. Either way, the $3 million award represents the profits Seirus made from the gloves.

In the Samsung Apple case, the court suggested Samsung might only have to pay the profits from the screen, not the phone (a lower court will decide). But Seirus had to pay profits from the glove, not the fabric.

“The jury might have thought that the fabric was heavily advertised as the most important part of the glove,” Aldrich said. “It’s not like Seirus was out there selling the gloves because they’re waterproof.”

A likely explanation for the jury’s decision is that advertising and promotion for the gloves—prominent wave images and slogans inviting consumers to “look inside” and “see the silver lining”—centered on the infringing technology, and Seirus probably wouldn’t have sold many gloves without Heat Wave.

Things didn’t turn out so badly for Seirus. There were two types of patents at issue in this case: utility, or how the product functions, and design, how it looks and feels. Columbia won damages because the Seirus wavy design on its Heat Wave products looked like the waves in a Columbia-patented design, not because Heat Wave functioned in a way that infringed on a patent.

It didn’t make a difference what consumers were thinking when they purchased Heat Wave gloves. Even if consumers bought the gloves because of how they worked, the infringement was based on the look of the wave pattern.

“The long and the short of it is that people buy products because those products do things (i.e., they have utility),” Aldrich said. “But designs are often used to adorn products that people buy for functional, utilitarian reasons. The Patent Act allows the patent holder the total profits of the infringer, even where the product may be purchased primarily for utilitarian reasons.”

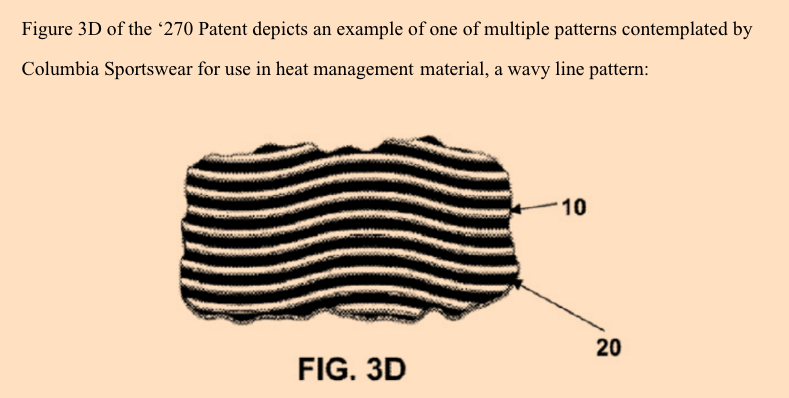

Screenshot from Columbia complaint

Screenshot from Columbia complaint

Columbia won damages for the design patent, but the jury found a portion of one of Columbia’s utility patents invalid.

That utility patent is arguably more important, as it covers the actual technological innovation of the product, not just cosmetics. The invalidation ruling strikes at the core of Columbia’s image. About ten years ago Columbia built an “innovation lab” and tried to rebrand itself as tech-savvy company. Omni-Heat became central to that approach.

RELATED STORY: Tim Boyle charts the future as Columbia Sportswear turns 75

“The jury invalidated one of the patents,” said Scott DeNike, general counsel for Seirus, “which Columbia characterized as core to the product line [Omni-Heat], that they spent more money promoting than any product line in their history and that they claimed resurrected their reputation as an innovative company.”

So Seirus can continue making Heat Wave work the same way it always has, DeNike said. The company just has to avoid the wave design, which they’ve stopped using anyway.

DeNike said both sides will probably appeal various parts of the ruling, so a full resolution could be months away.

“Seirus is confident in its ability to appeal multiple aspects of the design patent rulings,” he said.

Clarifications appended: This article has been amended to clarify the jury’s decision regarding one of Columbia’s utility patents. And in the fourth paragraph, Nika Aldrich did not say the Columbia trial was a “test case.” It is the first case addressing a precedent established in the Samsung ruling.