Just more than six months ago the Federal Reserve Bank raised the benchmark Federal Funds rate by 0.25 percent — the first rate hike in nine years.

The belief was that the job market was healthy and the Fed needed to start moving rates up to a “normal” level after seven years of virtually zero. When the Fed hiked short-term rates, the U.S. 10-year Treasury had a yield of roughly 2.5 percent. Fast forward six months, and the 10-year Treasury yields less than 1.7 percent and has been sitting at historic lows the past several weeks. This rally in the bond market has not been due to a pending recession or concerns over the U.S. job market; rather, we believe it is due to global investors seeking yield and reducing risk.

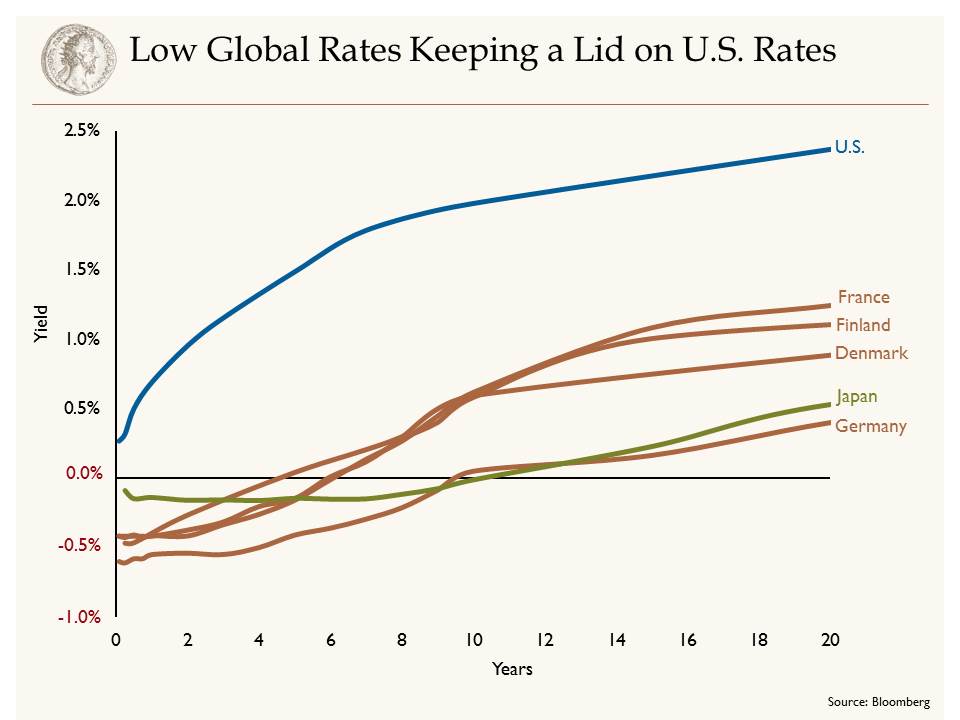

With respect to risk, the sovereign debt markets have historically been known as a virtually risk-free investment. When uncertainty increases in the capital markets, investors sell risk assets (i.e. stocks) and buy bonds. The current uncertainty is the pending vote in the UK to leave the European Union. We’ve seen stocks in the UK and Eurozone sell-off 3-4 percent the last month; when US stocks have rallied. Investors across the pond have flooded into bonds, driving yields down. The chart below highlights how low rates in Europe have gone. If you include Japan, there is more than $10 trillion of sovereign debt yielding zero or less.

Because yields are so low in Europe, global investors have flocked to the U.S. for their bond investments. Even though the U.S. 10-year Treasury has a historically low nominal yield, relative to the rest of the world, this is a screaming deal. Therefore, even with the Fed in a slow tightening cycle, longer-term rates in the U.S. will be under pressure as flows of funds from outside the U.S. comes in buying Treasuries. These low rates are great for borrowers. European based consumer products company Unilever was able to issue four-year debt to yield 0.08 percent. Toyota Finance Company issued three-year debt yielding 0.001 percent. There is not a precedent for negative government interest rates, therefore global investors (and savers) are involved in a new economic experiment.

Because yields are so low in Europe, global investors have flocked to the U.S. for their bond investments. Even though the U.S. 10-year Treasury has a historically low nominal yield, relative to the rest of the world, this is a screaming deal. Therefore, even with the Fed in a slow tightening cycle, longer-term rates in the U.S. will be under pressure as flows of funds from outside the U.S. comes in buying Treasuries. These low rates are great for borrowers. European based consumer products company Unilever was able to issue four-year debt to yield 0.08 percent. Toyota Finance Company issued three-year debt yielding 0.001 percent. There is not a precedent for negative government interest rates, therefore global investors (and savers) are involved in a new economic experiment.

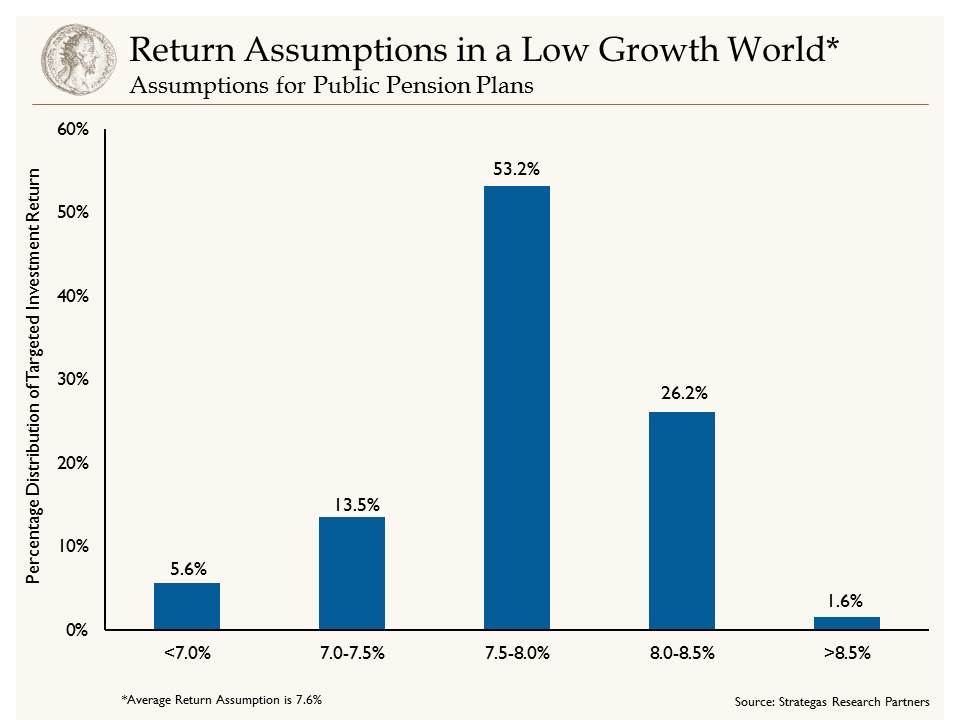

While these low rates are great for borrowers, savers are going to struggle to keep up with expenses, including individuals and pension plans. The chart below from Strategas Research Partners highlights that more than 80 percent of state and local pension plans have a return assumption of more than 7.5 percent.

When these targets are set, investment committees and trustees analyze historical data to make reasonable assumptions. Over the long-term stocks historically returned roughly 10-12 percent and bonds returned 4-5 percent. Therefore, with an allocation of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds, investors could expect a return of more than 8 percent. If you adjust assumptions to where bonds are yielding today, your expected return drops to around 7 percent (and this assumes no reduction in the return forecast for stocks). Savers are either going to have to increase the risk of their savings, or put more money into their savings accounts (again, this is also true for both individuals and pensions).

When these targets are set, investment committees and trustees analyze historical data to make reasonable assumptions. Over the long-term stocks historically returned roughly 10-12 percent and bonds returned 4-5 percent. Therefore, with an allocation of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds, investors could expect a return of more than 8 percent. If you adjust assumptions to where bonds are yielding today, your expected return drops to around 7 percent (and this assumes no reduction in the return forecast for stocks). Savers are either going to have to increase the risk of their savings, or put more money into their savings accounts (again, this is also true for both individuals and pensions).

The Other Side of the Coin

Last summer, the Oregon PERS plan reduced its return assumption from 7.75 percent to 7.50 percent. While more may have to be done, this is a step in the right direction. What makes these decisions very difficult is that when return assumptions are lowered, the pension plans need to contribute more funds (which come from taxpayers) or eventually reduce benefits. Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock, sums it up well: “Not nearly enough attention has been paid to the toll these low rates — and now negative rates — are taking on the ability of investors to save and plan for the future.”

Jason Norris is a Chartered Financial Analyst with Ferguson Wellman Capital Management