The problems facing rural Oregon won’t be solved by ceding control of federal land to the locals.

Now that the last protester has left the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, just south of Burns, it is time to scrape away the politics and the personalities, as well as the anger and the outrage. The protesters claimed they wanted the federal lands in the wildlife refuge — taken, in part, from the Burns Paiute Tribe after the treaty granting them in perpetuity was abrogated in the 1880s — turned over to “local control,” a euphemism for giving the land to local ranchers, or, in this case, ranchers from Nevada.

The overarching narrative here is that an uncaring and rapacious federal government is somehow denying the livelihood of these hardy, self-reliant constitutionalists. The implication is the local economy would be stronger if left to the locals.

But the history of this region tells us a different story.

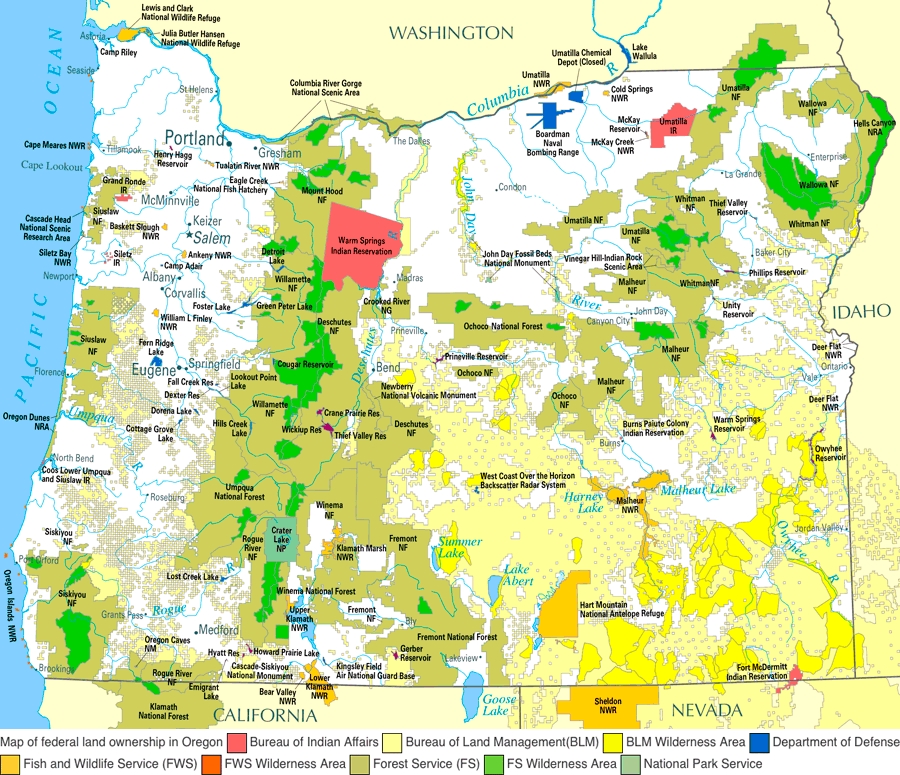

There’s little question that Harney County, like much of Eastern Oregon, has fallen on hard economic times. The county’s economy has always revolved around two big, resource-based industries: lumber and ranching. And since the federal government owns two-thirds of the land in Harney County, the decisions it makes as a landlord have a lot to do with the success of these industries.

Deference to local ranchers and loggers guided federal policy for more than a century. Nearly a century ago, at the behest of local leaders in Burns, the Forest Service gave the Edward Hines Lumber Company a long-term concession to cut timber from the Malheur National Forest, and in return, the company built a railroad spur, a sawmill and a company town: Hines, just outside of Burns.

Starting in earnest in the 1920s, the company harvested the huge, old-growth ponderosa pine trees in the Bear Creek stand in the mountains north of town (near the spot where the Oregon State Police arrested the Bundys and shot LaVoy Finicum).

For decades the Edward Hines Lumber Company was the county’s largest employer, and logging and wood products provided more than 1,000 of the county’s 4,000 jobs through the early 1990s.

In the mill’s heyday, it paid very good wages—the county’s per capita income was higher than the state average in the early 1970s. But the wood-products industry in this part of the world depended on mining the large-diameter old-growth ponderosa pines, which were the product of centuries of forest evolution. When these trees were cut, the forests were allowed to regenerate with faster growing, denser and less insect resistant stands of pine. Continual fire suppression turned the once open, healthy ponderosa forests into a diseased and dying ecosystem.

By the 1990s, most of the old-growth ponderosa pine had been harvested, and the forest health problems were becoming acute. Finally acknowledging the problem, federal forest managers reduced the allowable harvest on the national forest, and started looking for ways to remove damaged and diseased trees and restore a measure of forest health. The Hines mill was closed and resold, and re-opened on a much reduced scale as Snow Mountain Pine for several years.

But that too closed. Today there are essentially no wood-products jobs in Harney County. There’s been little overall economic growth in Harney County; the region has had about the same population (a little over 7,000) and about the same number of jobs (4,000 and some) for the past 25 years.

Ironically, Harney County, like many rural Oregon counties depends heavily on federal and state governments for jobs and incomes. On a per capita basis, Harney County residents receive about $10,500 per year in federal benefit payments like social security, Medicare and unemployment insurance, compared to about $7,100 per capita in the Portland metro area. The Oregon Employment Department reports that federal, state and local governments account for 44% of the county’s wage and salary employees and 57% of payroll.

But at least one part of the resource-based economy in this part of the world is figuring out how to prosper in the 21st century. Just a few miles west of Burns on Highway 20 is Brothers, Oregon, where starting a couple of decades ago, ranchers Doc and Connie Hatfield started working on how to get a good price for their range-raised beef. In partnership with their neighbors, the Hatfields started a cooperative enterprise called Oregon Country Beef — which has now expanded into several states as Country Natural Beef — and spawned a number of competitors. Their key selling point is strong environmental stewardship of the range. This business strategy isn’t about massive and unsustainable cattle feedlots but about an operation that is carefully scaled and managed to be sustainable in the special landscape of Eastern Oregon.

The economic challenges facing rural Oregon are real. But hoping to return to the economic heyday of the old ponderosa pine industry— and ignoring that the timber boom was built on ecological blunders and short-sighted liquidation of natural resources — is not an economic strategy. . This region will continue to be highly dependent on the wise management of its resources, especially its forests and rangelands. That won’t be accomplished by turning the clock backward: We could only cut the old-growth ponderosa pine once.

Instead, we’ve got to look for innovative ways to create value, just as Oregon Country Beef did by using the story of the landscape to help sell their premium product.

The notion that ending federal ownership of the wildlife refuge and range and forestland in Eastern Oregon would restore employment to some imagined past glory is mistaken. The region’s economic future depends critically on the wise and sustainable management of this extraordinary area — a lesson that we’ve learned at a high price.

Joe Cortright is a principal economist with Impresa, a Portland consulting firm.