Adapting to changing cultural norms, the Oregon Zoo pursues a conservation-oriented business model.

If you want to glimpse the future of the Oregon Zoo, head for the new education center, a $17 million LEED Gold, net zero energy wood structure. Inside, you will find a giant touch screen park locator, a species conservation laboratory, colorful kid-friendly information exhibits and peppy teen volunteers ready to give the low down on conservation research.

What you won’t see on this hot August morning are many animals, or, for that matter, people.

To see them, animals and Homo sapiens, venture down to the elephant exhibit. Crowds press against a nearby bridge and embankments, smartphones at the ready. All eyes and screens are on Lily, a five-year-old juvenile and one of the newest additions to the herd. She saunters toward the new dunking pool, and rewards the crowd with a shower of trunk water followed by a full body dip into the water.

The elephant exhibit at the Oregon Zoo / Jason Kaplan

The elephant exhibit at the Oregon Zoo / Jason Kaplan

These two exhibits, one high concept and the other more traditional, represent the different and sometimes diverging paths taken by the Oregon Zoo, and zoos across the nation. Cultural and economic norms are changing, and to adapt to these changes — growing concerns about animal welfare, millennials more interested in experiences than cages, shrinking public coffers — many zoos are reorienting their missions toward education and conservation.

Yet scaling back the traditional zoo exhibit model, one based on charismatic megafauna like elephants, is no easy task, and it is unclear if pared down zoos will attract visitors accustomed to seeing exotic animals.

“We have to be out there talking to and engaging that group [animal welfare activists], but we can’t lose sight that the majority of our visitors aren’t in their mindset.” —Grant Spickelmier, Oregon Zoo

To help fund pedagogical projects like the six month-old education center, the Zoo is ramping up its business arm, scrutinizing existing operations for efficiencies and new revenue opportunities while expanding after hours entertainment offerings; this past September, for example, the Oregon Symphony kicked off its inaugural Zoo concert.

These market-oriented projects supplement declining public funds. Yet some of the entertainment oriented initiatives also raise concerns about diluting the conservation mission. Financial and staffing challenges have added to the confusion: A Metro audit released this past winter described low employee morale, flat attendance and lack of financial vision. The audit attributed these problems to a single source: the Zoo’s failure to “defin[e] and creat[e] a shared understanding of conservation.”

Can the Oregon Zoo function as a conservation education organization and a market-oriented business? These are the competing goals the zoo aims to reconcile.

Don Moore, executive director of the Oregon Zoo / Courtesy of Oregon Zoo

Don Moore, executive director of the Oregon Zoo / Courtesy of Oregon Zoo

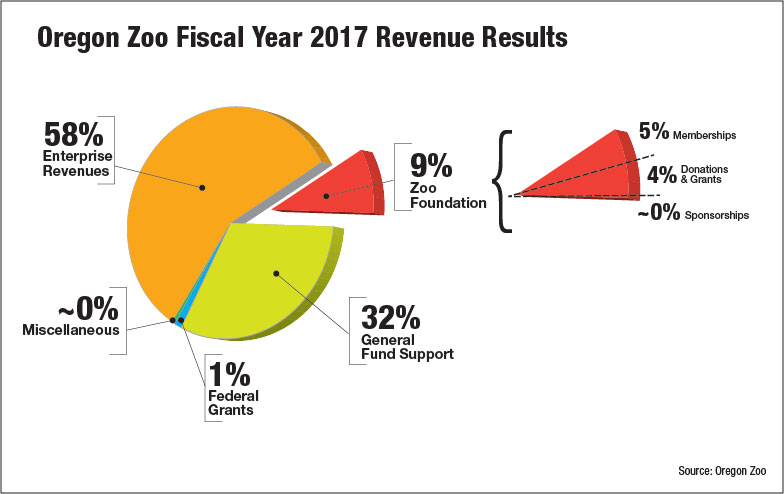

In 2016 the Zoo hired as its executive director Don Moore, a conservation biologist with a resume that includes an associate director stint at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and 10 years at the New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society. Within a year, the Zoo brought in a new finance manager and director for the Zoo Foundation, the nonprofit that handles memberships and contributes 9% to the Zoo budget.

These new hires coincide with shifts in the Zoo’s operating model. Metro has owned and operated the Zoo since 1976. But in 2015 the Zoo became its own enterprise fund within the regional government agency, which still oversees the venue and contributes 32% of its operating budget. Under the new model, the Zoo retains all profits but also absorbs losses if it goes into debt. (Throughout its 129-year history, the Zoo has also relied on bond measures to fund capital improvements.)

“We are the only conservation organization that pretty much runs on leisure dollars and the will of the people,” says Moore, standing on the walk between the elephants and Wildlife Live exhibit, amid the shouts and bustle of excited children and exhausted parents. “For modern zoos to get there with the leisure dollar and with donations is a very, very interesting business model.”

The conservation organization model Moore is referring to dates back to 2012, when the Zoo formally adopted the animal welfare, environmental literacy and conservation science mission. Four years later, the Zoo expanded on that goal by adopting a business model called the Integrated Conservation Action Plan, or ICAP. Under this model, all business decisions must prioritize conservation and education. It also means the Zoo’s business model must create the margin necessary to carry out the mission.

“We are looking at everything we do like every business does,” explains Sarah Keane, the Zoo’s finance manager. “So that we’re making sure every dollar counts.”

Moore calls it “no margin, no mission.”

Connecting zoos with conservation has become critical to their survival. Documentaries critical of animal entertainment venues have forced profitable venues like SeaWorld to stop breeding killer whales and end spectacles like the signature Orca show. Others, like Ringling Brothers Circus, have shut down entirely. Growing evidence that captivity is harmful to animals — especially large mammals — has altered public attitudes toward animal welfare and zoos in particular. Almost 80% of Americans are very concerned or somewhat concerned about animals in zoos, according to a 2015 Gallup Survey.

“Zoos don’t fit a nice didactic completion where there is a bad guy who’s harming the animals. When they do have a bad guy, it looks too much like us.” —Troy Campbell, University of Oregon

Elephant exhibits in particular have become flashpoints — and a harbinger for zoos that can’t or won’t adapt. Since 1991, 27 zoos have closed, or will be closing, their elephant exhibits, according to In Defense of Animals, an organization based in San Rafael, Calif. That list includes Seattle’s Woodland Park Zoo, which closed its elephant exhibit in 2014 after mounting public criticism.

“The public is going to demand better animal welfare,” says Matt Rossell, IDA’s campaign director. “And as they become more educated about the needs of these animals, and that they can’t be met in these small urban zoos, things will change.”

RELATED STORY: KEEP ON BUCKIN’

Animal rights activists are a thorn in the side of zoos. Even so, zoos say they have a bigger problem at hand: getting the population at large to even think about wild animal and habitat preservation.

“It’s an interesting challenge [addressing animal rights groups/zoo critics] because the percentage of people who don’t like zoos is actually fairly small but they’re very vocal,” says education curator Grant Spickelmier. “And so we have to be out there talking to and engaging that group, but we can’t lose sight that the majority of our visitors aren’t in their mindset. They still need to be encouraged to think about conservation at all.”

The ICAP model is aimed at getting visitors, and the zoo, to think about conservation. Consider one of the action items: creating worker focus groups to discuss considering the return on investment (ROI) of individual animal species. When the zoo talks about ROI they are talking about benefits for habitat restoration — a return on conservation, as it were — as much as a financial return.

Moore says he expects the framework to pare down the current list of 1,800 animals, although he declined to say by how much. The goal is to focus the zoo’s resources more intensively on select animals.

“That’s a return on investment that’s a bargain. Because you’ve got a wild thing flying back in the skies of Oregon for the first time since the Lewis and Clark expedition.” —Don Moore, Oregon Zoo

The conservation ROI doesn’t always square with the financial ROI, however. Some of the zoo’s most expensive animals are the animals that provide the highest visitor engagement — elephants for example.

“Between food and beverage and gift shop, you can do that kind of revenue and expenditure analysis,” Moore says. “You can’t do that with an animal unit. We’ve got zookeepers. We’ve got animals. We’ve got medication. Animals are changing. They’re aging all the time.”

Elephants in zoos are controversial, but the Zoo has established itself as a regional center for elephant research. Moore notes the Zoo has established a $1 million endowment fund supporting Asian elephant conservation. The Zoo partners with Borneo in its Asian elephant recovery program and recently invested $57 million on a new six-acre Elephant Lands exhibit.

“You can’t just say one keeper costs this for an elephant so we should get rid of the elephants,” Moore says. “Because the elephants are driving the mission…We’ve got huge engagement and huge conservation value despite the high cost, and so we say okay, elephants shouldn’t go away.”

The Zoo’s California Condor / Jason Kaplan

The Zoo’s California Condor / Jason Kaplan

The Zoo’s work on the California condor involves a similar cost benefit analysis. In 1982, only 22 condors were left in the wild, and by 1987, the last condors were taken into captivity in an attempt to save the species, Moore says. Today, condor numbers now total more than 400, with the majority living in the wild. Moore figures the Zoo’s costs to help with that effort over the past decade has been about $15 million.

“That’s a return on investment that’s a bargain. Because you’ve got a wild thing flying back in the skies of Oregon for the first time since the Lewis and Clark expedition.”

The new business model isn’t just about animals. Moore’s vision is for all Zoo employees to connect their jobs with conservation. He points to the beer sold at the Zoo’s restaurant as an example. Employees know that for every beer sold, money goes to support a habitat restoration project on Oregon’s North Coast called the Salmon Superhwy project.

“So rather than saying, ‘Would you like a beer with that?’ employees can say, ‘Would you like to have a beer with that to support salmon conservation research?

The Oregon Symphony performing at the Zoo in September

The Oregon Symphony performing at the Zoo in September

Few dispute that the Zoo is a much beloved Portland institution.

Over the past decade, the venue has received numerous national awards for protecting endangered species, exhibit design and operations. A 2016 survey showed that 95% of visitors said the Zoo met or exceeded expectations, and the Zoo continues to be the state’s most visited paid attraction, grossing $23.2 million last year in sales (up from $20.3 million in 2016), a category that includes admissions, food and beverage, retail and concerts.

These accolades and numbers disguise some of the challenges.

The Metro audit noted that the Zoo relies heavily on the $125 million bond measure voters approved in 2008 for capital expenditures. By comparison, the Oregon Zoo Foundation, the other major source for capital projects, is expected to contribute only $1 million in 2017, just slightly more than the past five years of relatively flat revenue. And while the Zoo attracted 1.49 million annual visitors in 2017, attendance has remained flat over the past 10 years, while operating expenses increased 22% adjusted for inflation, the audit cautioned.

Some of the zoo’s biggest critics come from within. Metro’s Accountability Hotline gives citizens and employees the ability to report misconduct, waste or misuse of resources. Between 2013 and 2015, about half the calls were related to the Zoo, and based on the concerns — communication, compliance with policies and procedures and management responsiveness to employees — the bulk of those appear to be from the Zoo’s nearly 900 employees.

Some questioned whether the organization was “walking its talk,” a reference to the animal welfare, environmental literacy and conservation science mission adopted in 2012. “Feedback from employees indicated that the Zoo faced challenges that went beyond any single event, employee or policy,” the audit says.

Moore says the internal criticism is unsurprising given the significant staffing and infrastructure changes the Zoo has experienced in the past few years. The $125 million bond measure helped pay for a new a veterinary science building and the new education center, along with new and expanded exhibits for condors and elephants. Still to come is a new habitat for polar bears, primates and rhinos. When construction is completed in 2020, 40% of the Zoo’s campus will have been renovated.

“A physical transformation of this magnitude has presented challenges to most, if not all, of our staff in their daily work,” Moore says.

The new business model is intended to help address some of the concerns outlined in the audit. Simultaneously, to stabilize Zoo funding for the long term, the Zoo is committed to growing its non-animal related entertainment division. The Zoo concerts series already accounts for 11% of revenues. A more recent off-hours venture, Twilight Tuesdays, features $5 admission after 4 p.m., along with samplings of local wines and beers and live music. Moore says the most recent Twilight Tuesday in August attracted 5,000 visitors — almost as many as typical daily attendance.

Twilight Tuesdays brings in visitors at a time when the Zoo would otherwise be closed. Now Moore and company envision using the ballrooms and conference centers for business conferences, weddings and other gatherings.

Twilight Tuesdays at the Zoo / Jason Kaplan

Twilight Tuesdays at the Zoo / Jason Kaplan

“One of our strategies is we are busy during the summer during our open hours, so how do we capitalize on those times where we don’t have a lot of folks at the Zoo,” Keane says.

While these are good ways of priming the pump, not everyone is happy about the new entertainment offerings. In 2016 the Zoo brought in a carousel to engage kids and encourage return visits. “Some people on my staff are not super excited about the carousel,” Moore acknowledges.

The Zoo, officials clarify, is not a conservation research organization; it’s a conservation education organization. Only 3% of the Zoo’s $40 million operating budget — under $2 million in 2017 — is actually invested in conservation research.

Going forward Zoo officials aim to give visitors more educational — and experiential — understanding of animals and habitat. One example is moving “back of the house” activities — feeding animals, veterinary sciences and conservation research — to the front and charging for them. “When we take people on a behind the scenes tour they’re absolutely fascinated with what we’re doing,” Moore says.

“Some people on my staff are not super excited about the carousel.” —Don Moore

A good example is the Zoo’s giraffe feeding program that lets visitors go behind the scenes with animal trainers. The $120 tickets sold out through September. Sensing a hit, the Zoo recently added a $20 giraffe feeding “light” program.

“If you can have a foot long blue tongue wrapped around your hand, that’s pretty awesome,” Spickelmier says. “At the end of the day, live animals and that authentic experience — that is our unique value. That is what the visitor looks for when they come to the Zoo: ‘How can I connect with a live animal’?”

Partnerships with nonprofit and government agencies help reinforce the conservation message — and maximize resources. Moore points to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which operates a full time office out of the education center with a full time employee. On this August morning, a group of kids, iPads in hand, are learning how the USFWS uses CSI-style methods to track and arrest illegal sellers of elephant ivory.

“This zoo is incredibly progressive,” says Leah Schrodt, the interpretive lead in the Oregon Zoo Partnership with USFWS. “It’s given us an additional audience that we otherwise wouldn’t be able to work with.” The Zoo in turn gets access to 200 USFWS biologists, Moore says.

To monetize these experiences, the Zoo is considering tiered pricing for different activities, be it feeding giraffes or getting a behind the scenes tour of the veterinary science building.

Peak pricing is another strategy. Zoo tickets are relatively cheap compared to other comparable venues: $14.95 compared to $22.95 for the Oregon Coast Aquarium and $20.95 for the Woodland Park Zoo. Raising admission prices seems like a business no-brainer. But Moore and his team are reluctant to raise prices for fear it will exclude poorer populations.

Many of the Zoo’s new program and price structures draw on amusement park models. But conservation organizations are not amusement parks, and the Zoo faces hurdles as it crafts messaging around its business savvy conservation model.

Troy Campbell, a marketing professor at the University of Oregon, neatly sums up the challenge. Successful theme parks, he says, create heroes and villains, what’s known to marketing psychologists as “agent and patient.” So the villain might be Captain Hook or Darth Vader or Voldemort — someone you can root against and vanquish.

The Zoo, however, finds itself in a unique and prickly position: In many ways, the visitor is the villain. “Zoos often act like they’re the good guy, but they don’t fit a nice didactic completion where there is a bad guy who’s harming the animals… When they do have a bad guy, it looks too much like us,” Campbell says.

The Carousel, installed in 2016

The Carousel, installed in 2016

In other words, we (the zoo visitor) have seen Voldemort, and he is us: destroyer of the environment and big animal habitats. It’s not the most uplifting or entertaining message. “A large percentage of people working for zoos agree with the critiques of them,” Campbell says. But this messaging challenge is exactly why zoos are struggling, he argues.

Moore makes a similar point when he chastizes zoo critics.

“The thought is these animals should be out flying free,” he says, referring to the condors perched in the fake trees of the netted exhibit. “Well, there is no free, and there is no wild anymore. Every single space on the planet is now managed somehow by humans. What we have is small slice of space. And these animals, yeah they’re in captivity, but they’re producing babies for the wild population.”

But maintaining the zoo as a conservation space costs money.

To renovate the remaining 60% of the campus, Zoo leaders may support a second bond ask after 2020 when the current bond ends. In the meantime, they are eager to demonstrate how well they are stewarding public dollars with ICAP.

Will the Zoo of the future succeed with a handful of carefully curated animals, hands-on animal tending experiences, an education center and lots of profitable, after hours entertainment? Cultural norms are changing, but for the zoo perhaps, not fast enough.

Zoos have to shift, but so do public attitudes, Moore says.

“People recognize zoos as amusement and entertainment centers,” he says. “We’re a cultural institution, just like museums. We just happen to be a living museum. So when the public thinks about professional zoos and aquariums as cultural institutions, maybe their mind shifts in terms of how to give us money or time, with the recognition that we’re trying to be a good business at the same time.”