Companies chuck thousands of tons of food a year. Now they’re on a mission to unspoil the future.

Punky Scott hated seeing uneaten portions of chicken-fried steak being tossed in the trash at her restaurant, The Bomber, in Milwaukie.

So she offered customers a half portion — and then signed on for the Metro regional government’s voluntary food scraps composting program. Now, less leftover chicken-fried steak comes back, and what does goes into one of her new compost bins.

“I’m saving on garbage fees, which I love!” she says. “And I’m helping the environment.”

Punky Scott, owner of the Bomber in Milwaukie

Punky Scott, owner of the Bomber in Milwaukie

Already at the forefront of food waste reduction efforts nationwide, Oregon businesses are ramping up efforts to winnow the waste. (In garbage speak, “food waste” refers to both edible food scraps and the inedible leavings: eggshells, bones, etc. These are important distinctions, for reasons to be discussed later in this article.)

More businesses are composting, donating to food banks, and — like Scott — monitoring portion size more closely. Avoiding unnecessary food purchases helps companies save money, while donations feed the hungry and are good for the corporate image.

Private-sector efforts are getting a push from new Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and Metro policies designed to severely limit the amount of commercial food waste.

Add to that an elite group of food providers who are using smart tech and other tools to track and analyze waste, fine-tune their purchasing and preparation techniques and create connections with nonprofits. Their goal is to reduce the waste both before it gets to the consumer and afterward.

RELATED STORY: GENERATION DINER: WHY EVERYONE YOU KNOW IS EATING OUT

Oregon is known as the nation’s foodie epicenter.

But we live in contradictory times. And as hunger, homelessness and environmental linkages get more attention, the next big thing in food may be the waste it creates.

The solutions are coming from businesses and nonprofits large and small, and their leaders are quickly becoming the new environmental superstars.

“Customers vote with their purchasing dollars, and the more votes we can get in Portland to relax the stringent standards at retail, the closer we can come to eliminating that waste,” says Evan Pence, the general manager for Imperfect Produce, a Bay Area company that launched in Portland last spring, selling misshapen fruits and vegetables that conventional grocers would otherwise toss.

A cultural preference for impossibly perfect, Instagram-worthy fruits and vegetables is one reason Americans squander so much food.

And in a country where 20% of produce is diverted away from grocery stores because of appearance, changing consumer attitudes, Pence says, “is crucial.”

Oregon likes to tout its conservation credentials. And businesses aren’t exactly keen to reveal how much food they waste. But the macro figures are eye-popping.

According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, households and businesses threw away 133 billion pounds and $161 billion worth of food in 2010. A 2014 study by the Food Waste Reduction Alliance found that 84.3% of unused food in American restaurants ends up being disposed of; 14.3% is recycled, and only 1.4% is donated.

Businesses are responsible for tossing a whopping 100,000 tons of food waste annually — 55% of the Portland region’s total, Metro reports. In the metro area, food represents 18% of all garbage that goes to landfills — the largest component in that waste stream.

Landfilled food provides ready fuel for methane gas production — the most environmentally destructive greenhouse gas linked to global warming. Households can decrease their food waste and put more in the compost and less in their garbage. But experts say the big opportunity for diverting food waste from landfills lies with Oregon’s commercial food businesses: grocery stores, hospitals, large restaurants and cafeterias. .

Providence Health & Services system workers compost food scraps. Serving right-size meals that don’t go to waste is one of the dining industry’s biggest challenges.

Providence Health & Services system workers compost food scraps. Serving right-size meals that don’t go to waste is one of the dining industry’s biggest challenges.

To see first hand how these venues are tackling the problem, Oregon Business stopped by Providence Portland’s basement cafeteria.

Today’s lunch — for under $6 — comprised fresh fish with a mango salsa, fresh sauteed green beans and mashed sweet potatoes. The deceptively simple meal reflects a wealth of behavioral and data science aimed at getting people to eat everything on their plates.

“Post-consumer waste is the most difficult to control,” says Mike Geller, Providence Health & Services sustainability manager.

Create a tasty, well-portioned meal, says Geller, and diners will be less likely to throw away perfectly good food. “You can always come back for more, but if you plate too much initially, it’s excessive and it’s wasted.”

The Providence health system’s eight Oregon hospitals and clinics serve 15,339 meals daily.

There’s an uncomfortable truth behind composting food waste. It’s better than landfilling, but the practice often involves throwing away food that could have been eaten. After all, there is no shortage of compost in Oregon.

To improve efficiencies, Geller and Kas Logan, senior manager of culinary operations, moved several years ago to a centralized food purchasing program that supplies all Providence chefs. No chef can buy food outside the central program without prior approval from the regional purchasing team. This team seeks out vendors, negotiates contracts and supports food waste reduction efforts.

Last year rigid recipe, nutrition and portion control helped Providence divert 204 tons of food waste from the landfill.

Some of the waste diversion stemmed from Logan’s annoyance with the amount of vegetable food waste from the prepping process. She found a vegetable vendor that agreed to preprocess everything in exchange for a bulk order from Providence. It cost more than unprocessed food, but the end result, she says, “was 100% usage.”

Making a robust business case for tackling food waste is critical for the cause, says Athena Petty, sustainability manager for New Seasons Market.

Bread from New Seasons Market, headed for the compost pile.

Bread from New Seasons Market, headed for the compost pile.

A graduate of the University of Oregon’s journalism school, Petty now oversees a company-wide composting program. Some of the food scraps collected by New Seasons’ waste hauler goes to a facility in Junction City and other regional facilities that produce biomethane energy.

“The costs around food waste are based on weight,” Petty says. “Because we are diverting [from the landfill] to the composting stream, we are saving 2.5 times the cost. It’s huge from a business perspective.”

There’s an uncomfortable truth behind composting food waste:

It’s better than landfilling, but the practice often involves throwing away food that could have been eaten. (After all, there is no shortage of compost in Oregon.)

For that reason, the holy grail for so called “zero wasters” is making sure all food that is harvested, processed and purchased gets eaten. Hence the need to distinguish between edible and inedible food waste.

Most companies have yet to track how much edible food waste is composted or goes to the landfill.

For example, New Seasons says in 2016, a waste audit of some locations found that the chain diverted 84% of all waste from landfills via composting, food bank donations, recycling and vendor take-back. Providence doesn’t break down food waste by edible or nonedible categories either.

RELATED STORY: ARE INSECTS THE NEW QUINOA?

But the momentum is moving in that direction. New Seasons is focusing on tracking food waste using internal tools and processes, designed to produce “better data to access our purchasing and ordering practices,” Petty says.

“Unless we can understand through data what is happening with the food, it’s hard to order accurately. We want to order as close to our sales as possible so that we can proactively reduce the amount of food waste.”

Strawberry tops in the compost, from The Bomber

Strawberry tops in the compost, from The Bomber

Restaurant owners echo Petty’s assessment.

“Restaurants can see a substantial cost savings simply by accurately ordering according to need, then correctly portioning each item they sell,” says Scott Brandstetter, assistant general manager of Neuman Hotel Group in Ashland.

“Too often misordering can lead to waste due to spoilage.” Adds John Gorham, owner of several Portland restaurants, “[Purchasing] is the difference between a great chef and a good chef.”

But even money-conscious chefs run into problems. Sarah Pliner, co-owner and head chef at Portland’s Aviary, notes that most Portland-area restaurants really can’t afford to waste food products. Margins are too low.

“Unless we can understand through data what is happening with the food, it’s hard to order accurately.” — Athena Petty, New Seasons Market

The bigger issue is meeting consumer expectations for large-portioned, moderate-priced meals, she says. “Anywhere I go in Portland I get more food than I can handle,” Pliner says. “The expectation of enough people is for large portions, and they Yelp you if you don’t meet that. It hurts your business if you get that reputation.”

Oregon food-waste crusaders pop up in the most unexpected places — like Portland-based Salt & Straw, the ice cream retailer that has virtually no food scraps to be composted but wanted to be part of the solution anyway.

When the shop does offload ice cream that is no longer on its menu, that product goes straight to Urban Gleaners, a nonprofit that gathers uneaten food to give to the needy. Salt & Straw became a gleaner in its own right recently when it decided to highlight food being wasted in the U.S.

The shop created ice cream flavors with overripe strawberries, spent brewing grains and near-expiration date vegan mayonnaise earlier this year. Proceeds from the sales of the featured flavors from its Portland stores ($3,000)were donated to Urban Gleaners . The national media ate it up.

“The lesson here is that food waste can be turned into magical food,” says co-founder Tyler Malek.

Deschutes Brewery in Bend uses spent grain as a recipe ingredient.

“Instead of sending this by-product of brewing to waste, we use it in the pubs to create handcrafted breads, pizza dough, pasta and even our veggie burger,” says Mike Rowan, director of food and beverage. “In true circle-of-life format, even the burgers come from freshly ground, locally farmed cattle, which are grass fed and finished on the brewery’s spent grain.”

Robb White, LeanPath executive chef, demonstrates food waste monitoring software.

Robb White, LeanPath executive chef, demonstrates food waste monitoring software.

As restaurants, major food servers and grocery stores experiment with reduction strategies, new businesses are springing up to grind even more finely on reducing food waste.

Imperfect Produce decided to come in to Portland “based on expectations of the people being extremely receptive to our mission,” says Pence. The company has exceeded initial expectations for the Stumptown launch and aims to expand out into other markets around the metro area, he says.

Like Pliner, Pence says consumer expectations are a major stumbling block to slashing food waste. But purveyors can help change those expectations.

“It’s time to recognize our role as food producers and our expectation to make fresh produce, of all shapes and sizes, affordable and available to everyone,” Pence says.

“The expectation of enough people is for large portions, and they Yelp you if you don’t meet that. It hurts your business if you get that reputation.” — Sarah Pliner, Aviary

Another small business with a huge impact on food waste, LeanPath, based in Portland, has developed proprietary technology for commercial kitchens that includes a built-in scale, camera and touchscreen user interface.

One product, LeanPath 360FS, is attached directly to the waste bin. When employees toss the leftovers, a smart meter automatically registers the weight change and initiates a transaction.

“You either track your waste or you don’t,” says Robb White, LeanPath’s executive chef and food-waste prevention catalyst. “If you don’t track, you don’t really know how much you’re wasting.” Most of LeanPath’s clients are universities, casinos, cruise ships — “global companies that manage hundreds if not thousands of food operations,” says CEO Andrew Shakman.

As commercial food businesses tweak operations, allies in the nonprofit and government worlds are ready to work with them hand-in-hand. Oregon’s commitment to be at the forefront of the zero waste effort drew a food-waste rock star to Oregon DEQ: Ashley Zanolli.

She’s on loan to the state agency from the federal Environmental Protection Agency. There, she carved a reputation for such innovative, high-profile national initiatives as “Food: Too Good to Waste,” a consumer guide to reducing waste that started local and went viral.

Now Zanolli is working on the DEQ’s “Strategy for Preventing the Wasting of Food,” a framework finalized in March 2017. The plan outlines a strategy — heavy on metrics and messaging — over a five-year period to encourage reductions in the wasting of food across the supply chain.

“I came to Oregon for a reason,” Zanolli says. “[The state] is on the cutting edge. This is where the leadership in food waste reduction is most heavily concentrated.”

Pam Peck, Metro’s resource conservation and recycling manager, is part of that leadership. A dozen years ago, Metro launched a voluntary food scraps program — one of the first in the nation. Some 1,270 businesses signed up. But Metro wants more participation, and Peck estimates as many as 3,000 businesses should be involved, based on the amount sent to landfills.

So the regional government is now in the final stages of developing a mandatory food scraps program that would eventually prohibit companies in the program from sending any food scraps to the landfill.

Not all businesses are keen on the regulations.

“This kind of regulation can make it difficult to do business and be successful in an industry that’s already quite a challenge,” says Greg Astley, of the Oregon Restaurant and Lodging Association. “It’s one more straw on that camel’s back.”

ORLA believes participation in the composting program should remain voluntary. But, Astley says, if Metro is determined to push forward with a mandatory program, it should start with public food service entities — schools and prisons — and fold in the private businesses later.

Peck says she knows it’s cheaper for businesses to send food waste to the landfill. “But the cost to the environment in terms of methane gas production and other negative effects is too great. We can help businesses find ways to reduce the cost, but participation will no longer be voluntary.”

The DEQ is also offering $600,000 in grants aimed at helping businesses curb food waste.

Athena Petty, New Seasons Market sustainability manager

Athena Petty, New Seasons Market sustainability manager

Nonprofit organizations are tackling a component of food-waste reduction that has little to do with the environment but everything to do with Oregon’s hunger and homelessness problems.

“We could easily feed every hungry person in this region,” says Greg Baker, executive director of the Blanchet House, a Portland shelter that receives donated food from multiple sources and serves more than 1,000 meals daily to the needy. “It’s just a matter of connecting all the food that’s going to be thrown away that’s still perfectly good with the people who need it.”

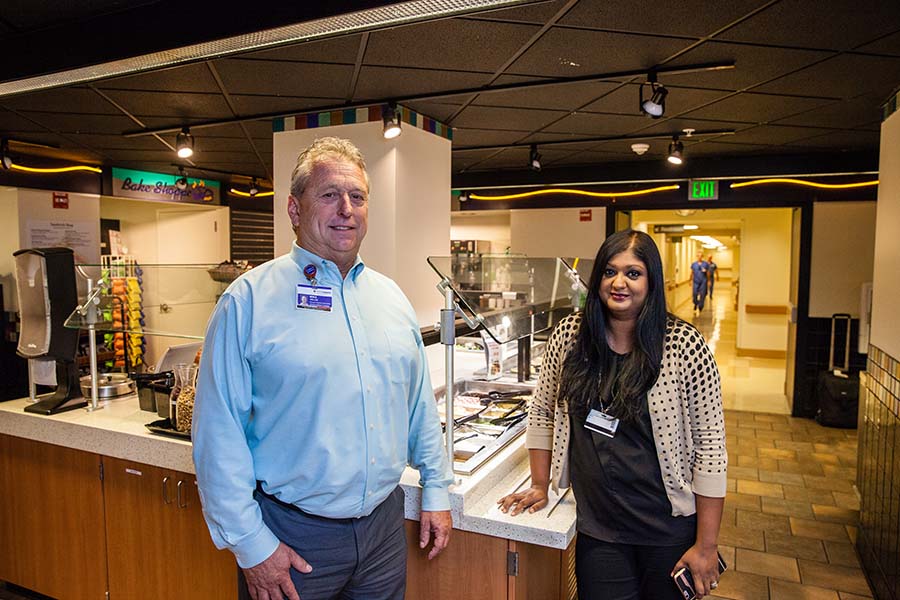

Michael Geller and Kas Logan head up the Providence effort to slash food waste.

Michael Geller and Kas Logan head up the Providence effort to slash food waste.

Here’s another uncomfortable truth: At the end of the day, every day, grocery stores have far more leftover food than they know what to do with. This is why Petty of New Seasons underscores the importance of accurate purchasing.

The chain does have connections with food pantries at each of its Oregon stores that make daily pickups of donated food. Fred Meyer’s 133 West Coast stores are on track to donate about 8 million pounds this fiscal year to food banks that collect it from the stores. Each store averages about 4,600 pounds of donated food a month.

Urban Gleaners, pays drivers to pick up and deliver food on a schedule. But, says Baker, too many gleaners and food pantries rely on volunteer drivers who may not stick to a schedule. Large food providers can’t work with that. Especially in rural areas, the lack of a reliable pickup and delivery service makes donations difficult.

“I came to Oregon for a reason. “[The state] is on the cutting edge. This is where the leadership in food waste reduction is most heavily concentrated.” — Ashley Zanolli, DEQ

New sharing-economy businesses could help solve the problem.

A new service, Copia, has sprung up in the San Francisco Bay Area to connect food with the hungry in a seamless fashion. Built on the Uber model, an app connects roving drivers with food providers and food pantries.

DEQ’s Zanolli says the model holds promise. But there are issues to be ironed out, such as proper transporting of hot foods or frozen foods to locations that may not have the facilities to properly store them.

A recipient of food donations, Blanchet House is itself a pioneer in food waste diversion. The nonprofit sends food matter that might go to the landfill, or even to composting, to a hog farmer who regularly picks up the waste. “We’re the perfect example of zero food waste,” Baker says.

Source reduction has on average six times the greenhouse gas benefits as composting the same ton of food.

Farmers in The Ashland Food Co-op’s “Food to Farm” program likewise come daily to pick up nutrient-rich food scraps to feed to farm animals or turn into compost. That alone diverts 150 metric tons of food scraps away from the landfill, about 15% of all the co-op’s waste by weight.

“But you have to be committed to finding those farmers who will show up every day,” says sustainability manager Stuart Green. “Not every grocery store is going to have that type of culture.”

Rural areas face other challenges. Most small towns aren’t served by garbage haulers that can take compost. Providence can’t compost at its Medford hospital due to a lack of haulers to collect waste.

Here’s another uncomfortable truth: At the end of the day, every day, grocery stores have far more leftover food than they know what to do with.

Adding to the problems in urban and rural locations: packaged food that’s expired and can’t be composted unless it’s “depackaged.” Trader Joe’s depackages its food waste for this reason, but most large chains don’t.

There are other gaps and trade-offs that frustrate the zero-wasters. Providence diverted Portland food waste from a landfill in Seattle, where food waste and compostable fiber was composted, to an anaerobic digester.

“But we had to take out the compostable fiber, so more of that went to the landfill,” Geller says. Ashland Food Co-op’s Green worries about how to compost the 100% compostable takeout containers from the store’s deli when customers toss the empties, now contaminated, in the co-op’s garbage. “No one will pick them up,” he says.

These roadblocks help explain why tons of food scraps are sent to the landfill every day. Oregon still has a long way to go to catch up with, say, France, which has banned supermarkets from throwing away food by directing them to compost or donate all expiring or unsold food.

Germany is focusing on the issue in part by targeting the consumer side of the problem: namely, expiration dates, which many argue are arbitrary and encourage people to throw away perfectly good food.

The DEQ framework does include an action item around expiration labels.

Nor are we seeing social media posts — or food festival demonstrations (Feast Portland, anyone?) — featuring scrap-inspired meals like cheese rind stock and beet-top pesto.

Despite these challenges, the energy and momentum around this issue is palpable.

Americans have treated food as a not-very- valuable commodity for a long time. But the high human and environmental costs are now undeniable; no longer a luxury, wasting food is becoming, in some sense, a crime.

As regulatory solutions move forward, the state’s socially minded entrepreneurs are well positioned to advance market solutions. And every day, mainstream businessses big and small are taking steps to solve the problem.

So when you dine at The Bomber in Milwaukie these days, you’ll still get a large order of french fries with your burger. But you now have the option of ordering sweet potato fries, about half the size of the french fry portion, says owner Scott. It’s become a popular “substitute” for traditional fries, and no one complains about the portion size.

“I’ve got a very loyal customer base,” she says. “A lot of them like large portions. But if I make changes to the menu, like smaller portions or healthier substitutes, they’ll support me.”

A version of this article appears in the October 2017 issue of Oregon Business.