An OHSU neurosurgeon challenges the profit-oriented system of bringing new drugs to market while championing the small companies commercializing advances in brain cancer treatment.

Brain surgery famously vies with rocket science as the most demanding intellectual field of work. One thing may be more difficult: coming up with a better way to treat brain cancer. Portland neurosurgeon Edward Neuwelt has done both.

Yet, as Neuwelt tells his tale, it’s been even harder to push discoveries from his laboratory out into the world where they can benefit more patients and do a greater good.

Two decades of persistence and millions of dollars of publicly funded research by him and others are about to pay off. Two medical products largely developed in Neuwelt’s research group have reached the final stages of securing U.S. regulatory approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). More are in the pipeline.

Along the way, Neuwelt has found himself at odds with other cancer doctors and his employer, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU). He also has alternately challenged the money-making system of bringing new drugs and diagnostics into the marketplace and served as head cheerleader for the companies shouldering the business end of the products his research has enabled.

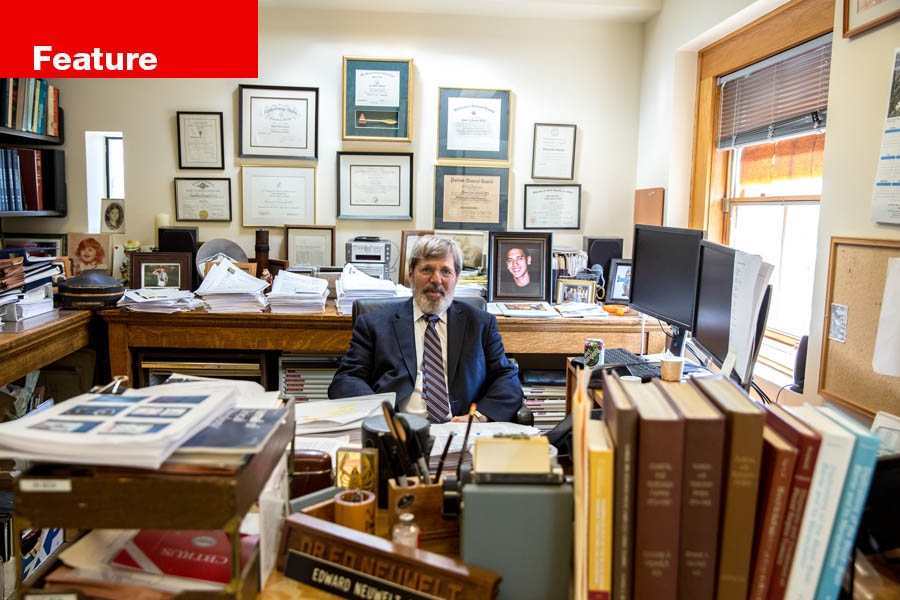

Neuwelt’s administrative offices and research laboratories occupy the attic floor of McKenzie Hall, one of the oldest buildings on OHSU’s hilltop campus in Portland.

Outside his office door, Neuwelt points out a scenic painting of a tall dock at low tide on the Oregon Coast. He bought it from an artist in New Mexico who had lost her vision due to lymphoma of the central nervous system. She recovered her sight after coming to Oregon for his medical team’s signature brain cancer treatment.

Neuwelt’s approach has worked best so far with her type of cancer, especially in people younger than 75 whose bodies can tolerate the year of monthly intravenous procedures and chemotherapy.

But many other brain cancers have eluded medical science. On a recent June day, Neuwelt has returned from a national cancer meeting, noteworthy for news of failed large clinical trials. He’s stewing over the negative findings of one study in particular.

“I’m just sick about it,” he says. The company-sponsored clinical trial tested the drug in glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer, and found no benefits when it checked interim results. Neuwelt thinks not enough drug reached the brain tumor. “They did the wrong experiment. It might be a really good drug if you can get it to the target. If you can’t get it to the target, you can’t test it.”

Neuwelt wants to try a small study himself, in a way that delivers more of the drug to the brain using his signature technique. He doesn’t want to name the company, because he hopes it will provide the drug for his studies and because he sees it as a problem larger than one firm.

“Primary and metastatic brain tumors are an increasing problem because drugs are working outside the brain,” he says. “We need to get past the business interests to do the key experiments.”

Neuwelt’s technique for pushing drugs to brain cancer feels risky to companies, he says, because an unexpected side effect could torpedo the drug’s chances for regulatory approval. “Companies have their own agenda.”

Early in his medical training, a mentor advised him to steer clear of financial relationships with companies. “It’s a crass thing to say, but they are out to make money. That’s not evil, but drugs are too expensive.”

Neuwelt took the advice to heart, building a brain cancer clinical and research enterprise largely based on consistent federal funding and going to extreme lengths to avoid conflicts of interest that might interfere with his research.

“We can’t be that pure anymore,” he says. “We have a more balanced portfolio now.” But he remains adamant about not doing contract work for drug companies that could compromise the research. “I deal with companies only when there is a win-win deal, when the science can be advanced, both pre-clinically and clinically,” he says. “I’m funded by the clinical practice and by grants. Because I have both of those, I have more independence.”

For 40 years, Neuwelt has concentrated on finding safer and more effective ways to target drugs to brain cancer. Despite decades of scientific progress, the basic clinical challenges remain the same.

“The biggest problems in neuro-oncology are that we don’t have drugs that don’t injure the brain,” he says, “and then we don’t test them with effective delivery.”

Getting drugs into the brain has always been a big challenge for treating brain cancer. The brain has the security of an air-traffic control tower. It is laced with blood vessels, but the vessels have layers of cells and other defenses to restrain toxic substances circulating in the body from seeping into the brain, including penicillin and chemotherapy drugs.

The core of Neuwelt’s enterprise is a technique he pioneered called blood-brain barrier disruption. He began his research at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and brought it to Oregon in 1981. His clinical and research teams have been refining the method ever since.

Neuwelt got the idea from a staff researcher at the National Institutes of Health whose skeptical boss had shut down the program. Good cancer drugs existed, Neuwelt reasoned, and some might work against brain cancer if they could reach it. Neuwelt flew from Dallas to Washington, D.C., to learn the technique and was advised to “work out the kinks” on animals first.

After a few years, the procedure was ready to test on humans. It worked better on certain tumor types. “We were the first group that showed complete and durable responses without radiation by enhancing drug delivery,” Neuwelt says. “And there’s no cognitive loss.”

For lymphoma of the central nervous system, Neuwelt’s team has achieved a median survival of 12 years in the latest regime, with several patients alive 30 years after the early version. The results have drawn several hundred patients from across the country.

While treating patients for brain cancer, Neuwelt pioneered a preventive treatment for hearing loss, a side effect of platinum-based chemotherapy. His scientific crusade to push the treatment through testing to the FDA led to skirmishes with his employer, OHSU, and U.S. pediatric oncologists. His persistence also serves as an example of how physician scientists can be surprisingly effective in piloting their own work through the regulatory process.

The hearing-loss treatment came about when the husband of a cancer patient from Washington, D.C., was concerned about his wife’s hearing loss. It was an unexpected side effect from carboplatin, a chemotherapy agent, delivered into the brain. More important, he had an idea worth testing.

The husband, David Scheim, an information systems manager at the National Institutes of Health, had searched the medical literature database for solutions. He found a report of a substance that could protect animals against a toxin vaguely similar to carboplatin. The substance was sodium thiosulfate, an old-school remedy for acute cyanide poisoning.

The next time the couple flew out to Oregon, Scheim brought vials of the substance, asking if Neuwelt could drip it in her ear during treatment. Neuwelt wouldn’t. But he agreed to test it on rats to see if it was safe and if it worked.

From the first study, sodium thiosulfate clearly showed it protected the rats’ hearing. The team worked out the dose and timing, finding a protocol that wouldn’t hurt the brain’s normal tissue nor interfere with the chemotherapy.

Then Peter Kohler, OHSU president at the time, threw a wrench in the works. He wanted to license this use of sodium thiosulfate to a company for hearing protection. Licensing a patented new use is a fundamental aspect of the U.S. technology-transfer system.

It is designed to encourage companies to license and develop scientific discoveries. In return, companies get exclusive rights to sell the product for a limited time, and universities and inventors share in the profits if it is approved and marketed.

The potential earnings could be worth a lot of money to both Neuwelt and the medical school, Kohler argued. Neuwelt did not need the money. He earned a neurosurgeon’s salary and had strong federal funding for his research. Kohler insisted, and Neuwelt had to withdraw a review article in a prestigious medical journal, which prohibited such authors from having a financial interest in the product. OHSU licensed the treatment to a North Carolina company now called Fennec Pharmaceuticals.

It took Neuwelt two years, but he successfully divested himself of all personal financial interest. “It’s extremely unusual,” says Erick Turner, a former FDA medical officer now in the psychiatry and pharmacology departments at OHSU.

Then OHSU created another potential obstacle. This time it was the OHSU Institutional Review Board, charged with protecting people enrolled in clinical trials. It nixed plans for a larger, randomized, controlled trial of sodium thiosulfate for hearing protection in adults, ruling it would be unethical to withhold it in a comparison study.

In short, convincing evidence showed the treatment worked, but Neuwelt could not take the usual logical next step to prove it.

He found another way. A related drug, cisplatin, is used to treat children with solid tumors not in their brains. Among other side effects, survivors suffer hearing loss with more severe consequences than adult survivors. The youngest have trouble learning how to talk and, through their teens, experience social isolation and a high failure rate in school.

A treatment for hearing protection could have a profound impact.

“The IRB [OHSU Institutional Review Board] said you can’t randomize adults on carboplatin, but they didn’t say you couldn’t randomize kids on cisplatin,” Neuwelt says. “It’s like playing checkers. You get one king and you have to protect that one to get another king.”

In fact, the director of OHSU’s Research Integrity Office wrote a glowing letter of recommendation for a large National Institutes of Health grant to support the research necessary to prepare for a larger study in kids.

Despite the continued good results, Neuwelt initially met resistance from U.S.-wide pediatric oncologists when he pitched a large clinical trial. They were concerned the hearing protection treatment would interfere with the impressive cure rate for cancer.

European pediatric oncologists, on the other hand, greeted the idea with enthusiasm and invited Neuwelt to help design the study. The results of both studies were published in top medical journals in the past two years.

This summer the FDA is expected to issue marketing authorization for sodium thiosulfate for hearing protection in childhood liver cancer. If that happens, it could be the first approved drug for hearing protection of any kind. A similar decision is also pending by the European regulatory equivalent, the EMA.

“They have two different approaches to medicine in children,” says Penelope Brock, a London-based pediatric oncologist who led the European clinical trial and later became a consultant to Fennec. “The EMA doesn’t want the child to be deprived of a drug that might be helpful. The FDA is opposite: They want to be absolutely secure in the indication.”

Neuwelt’s persistence has sustained more than the science. Fennec Pharmaceuticals, the company licensed to commercialize the treatment, credits Neuwelt with keeping them in business. He divested himself of personal commercial interest in the sodium thiosulfate drug he pioneered to conduct the clinical trials.

Now that all the work has been completed for the FDA, Neuwelt’s arrangement with Fennec and OHSU has changed to deal him into a share of the royalties, along with funding for research in his lab.

“This is really a story about a small company on the brink of extinction and the perseverance of a scientist out of Oregon looking to do good for mankind and for children,” says Rosty Raykov, president and CEO of Fennec. “This is how drugs should be developed in the future in small populations with real needs.”

From Raykov’s point of view, Neuwelt’s biggest contribution was working with Fennec to get orphan drug designation from the FDA, a special status for rare diseases that enables smaller studies and qualifies companies for certain incentives, such as tax credits.

“We escaped two to three times this thing being shut down. Studies were put on hold. Letters were going back and forth. I had to make a personal commitment.”

Raykov raised more money, and Fennec hung in there. “Ed is an absolute bulldog. He was essentially the glue for all of this. He stays on top of you, making sure you’re doing the right thing.”

Neuwelt can take more credit than most academics in pushing through the drug approval process. He has taken on many of the roles usually assumed in a complex interplay among inventors, academic institutions, venture capitalists, and small and large companies. Not only has he overseen the laboratory science, conducted the early-phase studies in people and designed the larger international pivotal clinical trials in people, he has also mastered the process of working with the federal regulatory authorities.

“He’s very cordial, a very good listener,” says Dwaine Rieves, former director of the FDA’s imaging product division, who is serving as a volunteer consultant for Neuwelt. “He has persistence and tact. I deal mainly with pharmaceutical executives. They’re very business focused, and rightly so. Ed carries his patient experience heavily into the boardroom.”

When he visits the FDA, Neuwelt is keenly aware of the contrast between himself, a self-described rumpled academic from the Oregon woods, and the usual pharmaceutical representatives in fine suits.

It will soon be easier for others to follow in Neuwelt’s footsteps. Drug development is one kind of pipeline, from the laboratory to the clinical market. Neuwelt has been working on another kind of pipeline, training people in a similar approach to translational science.

For 20 years, Neuwelt has helped lead a high school science program on Tuesday evenings in the spring. Private philanthropy has also been an important source of funding for Neuwelt’s programs. A new $2.5 million grant will provide stipends to high school students who work in OHSU labs over the summer and to the graduate student and professional mentors who work with them.

The money will also support college and M.D./Ph.D. students and junior faculty who pursue translational research in Neuwelt’s blood-brain barrier program.

People who teach say they learn as much in the classroom as their students. In Neuwelt’s case, it was strikingly true. Neuwelt has Parkinson’s disease. He first realized it while listening to guest speakers he had invited to the first high school class. For the class, two physician colleagues interviewed their father, who had been diagnosed years earlier with Parkinson’s.

The point of this lesson was to show how doctors practice a kind of science by asking questions, developing hypotheses and refining or changing their ideas based on results. “Kids don’t normally think of their family doctor as being a scientist,” he says.

Neuwelt was sitting at the back of the room, jotting down notes with a fat new Mont Blanc pen he had purchased earlier that day. Despite their medical training, the sons had missed their father’s earliest symptoms. In the front of the room, they asked their dad when he first knew something was wrong. It was when he had to use a larger pen to write clearly, the father answered.

“Oh, shit,” Neuwelt remembers saying to himself, looking at his new pen.

Neuwelt stopped doing complicated surgeries and finally stopped operating about 10 years ago. He moved from a house in the hills above OHSU, where he would routinely run around the popular Hewitt-Humphrey-Fairmount loops, to a place in the flatlands near the new OHSU Waterfront campus.

He rides an electric bicycle daily along the river for an hour or so, weather permitting, which helps with the stiffness and tremors on his right side.

“My wife thinks I should be combing the literature for treatments,” he says, but “I don’t focus on it.” He may be nearly shuffling, but he feels mentally sharp, which matters most to him.

Meanwhile, he’s working toward a dream of creating a specialty science high school in Portland that can churn out future Nobel Laureates and stimulate the local economy with highly trained people ready to work in patient-oriented scientific research.

Photos by Jason E. Kaplan

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.