Statewide fixes to Oregon’s mental healthcare system move forward — but not fast enough.

Multnomah County Commissioner Sharon Meieran began her career as an emergency room doctor. She saw patients suffering from mental illness — anxiety, depression, schizophrenia — nearly every day.

She quickly learned the mental healthcare system couldn’t meet patients ’needs. She recalls in particular one 14-year-old boy, who sat a windowless ER room, in his paper scrubs, for three weeks. He was not safe to go home. His family brought him to the ER because they couldn’t find treatment in the community.

Watch: Policymakers and advocates on mental healthcare in Oregon

Meieran got used to scenes like that. Oregon’s mental healthcare system, she says, is a Gordian knot of courts, government offices, emergency rooms, clinics and jails. These facilities rarely communicate.

“We have some community services,” says Meieran, “if you have the secret password and you’re able to navigate the systems effectively.”

Oregon ranks 44th nationwide for mental health treatment, according to Mental Health America, one of the nation’s largest nonprofits focused on mental illness. Patients wait months to get a diagnosis. More people receive treatment in jails than in hospitals. Those who do find medical treatment often get a bottle of pills and little else.

Mental illness strains law enforcement, the child welfare system and homeless shelters. Almost every person who was killed by Portland police since 2003 suffered from mental health problems. Many who are afflicted wander the streets, unable to find supportive housing.

There is some hope. After years of misguided funding strategies, legislators have heeded the call to expand and redirect treatment. An arsenal of new policies targets the statewide crisis. Housing projects, mobile crisis centers and new facilities have expanded care.

But it’s not enough. Not even close.

“That’s the biggest lie in the mental health business, that things are getting better,” says Jason Renaud, founder of the Mental Health Association of Portland, a nonprofit focused on mental health education and advocacy. “Very rarely do you hear of people who are well served by the system.”

A broken system

Oregon isn’t the only state facing huge mental health challenges. By some metrics, the state is doing a better job than most. Digging deeper into Mental Health America rankings, a composite of 15 measures, Oregon ranks 12th nationwide for access to care.

In 2013 37,931 Oregonians with a “serious and persistent” mental illness phoned a crisis hotline. Mobile crisis teams and walk-in community centers treated another 9,382. Oregon spent big on these treatment programs. That same year, the state ranked 11th in state per capita mental healthcare spending. Oregon shelled out $183, well above the U.S. average of $119.

40% of Oregonians described their mental health as “not good” for at least one of the past 30 days

25% of respondents said a doctor diagnosed them with a depressive disorder.

771 Oregonians committed suicide in 2016.

Source: 2015 Adult Behavioral Risk Factor and Surveillance Survey.

Yet no matter how much money legislators and private donors threw at the system, the dollars landed in the wrong places. Mental health advocates didn’t represent themselves well on the house and senate floors, Renaud says. Legislators didn’t fully understand the issues.

A U.S. Department of Justice investigation in 2014 found Oregon institutionalized too many people with mental illness, the department alleged. The state needed to pivot to more cost-effective community-based approaches.

The DOJ report noted that 74% of Oregon spending on serious mental illnesses went to “restrictive, institution-based settings,” including the state hospital and intensive inpatient treatment centers.

Jason Renaud, founder of the Mental Health Association of Portland

Jason Renaud, founder of the Mental Health Association of Portland

Chris Bouneff, director of the Oregon chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, puts it more bluntly. Too much goes to prisons and psych wards, not enough to clinics and housing.

“There isn’t a jail in this state that isn’t overwhelmed by mental health issues,” Bouneff says. “That’s because we’ve failed on the healthcare side.”

The Oregon State Hospital, where those judged to be criminally insane serve their sentences, requires upwards of $500 million to operate. People who are civilly committed or deemed unable to assist in their defense in court also get treatment at the hospital. It operates at a higher per patient cost than many private facilities. In 2013 one year of treatment cost $344,925.

Eliminating involuntary care is not the solution, says Pat Wolke, a Josephine County circuit court judge who chairs a working group seeking better ways to provide involuntary mental healthcare. Many people with mental illness don’t even know they have a disorder. They won’t check themselves into a hospital on their own.

“The vast majority of people with mental illness in the state don’t get treatment,” Wolke says. “We have this idea that people have the right to be mentally ill. That’s out of control.”

But there are other approaches to involuntary treatment. Assertive Community Treatment, a community-based outpatient model, costs pennies compared to the State Hospital. After Medicaid reimbursement and federal funding support, the DOJ noted, the model set the state back a mere $5,634 per patient.

“We have some community services,” Meieran says. “If you have the secret password and you’re able to navigate the systems effectively. Or if you have the stars align and your insurance covers it.”

Insurance restrictions make a bad situation worse. Despite recent mental health parity rules enacted in 2013, private insurance companies still don’t cover mental illness as thoroughly as physical disorders.

Many policies cover days, when doctors and therapists say they need weeks.

“The first thing we need is to get insurance out of the way of being a barrier to care,” says Andrew Delgado, a therapist at Adventist Health’s new behavioral health center, the Emotional Wellness Center. “The more services the better.”

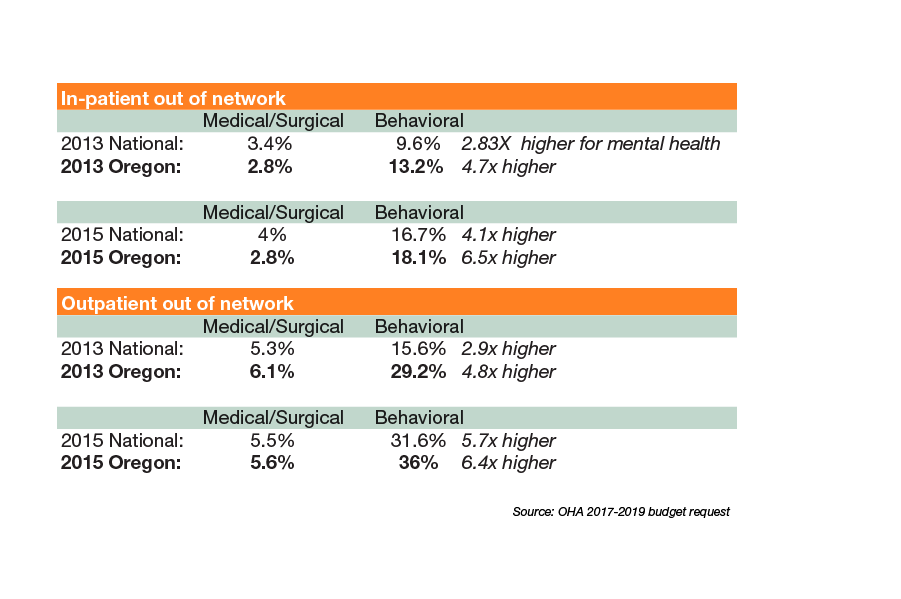

The Cost of Private Insurance: Compared to physical healthcare, a higher percentage of mental health care was provided out of network

These problems are bad enough in metro areas like Portland, with its well-funded cluster of hospitals and research centers. Cash-strapped rural counties face even greater challenges, says Sen. Floyd Prozanski (D-Lane and North Douglas Counties), who co-chairs a working group to decriminalize mental illness.

“Across the state but specifically in rural areas there’s a lack of resources,” he says. “Both in terms of funding and organization of services.”

Kathryn Chaney, a Pendleton-based volunteer who organizes NAMI events in Eastern Oregon, says the rural counties she serves lack places to take patients in an emergency.

“Due to the really sparse population and economic challenges,” she says. “We don’t have all these things right up front.”

Pendleton Creek, a voluntary overnight treatment center, has around five beds. The state recently approved Aspen Springs, a new 16-bed facility planned for Hermiston. Yet police still don’t have many places to take mentally ill people, besides jail.

Urban areas have far more funding. But more funding doesn’t fix the problem, unless it’s deployed efficiently.

“We have more people devoted to mental healthcare in Oregon than in some entire countries in Africa,” says Dr. Han-Chun Liang, who oversees youth mental health care for Kaiser Permanente. “We have a wealth of resources. Yet we’re still in a crisis.”

“The first thing we need is to get insurance out of the way of being a barrier to care,” Delgado says.

Attempts at Reform

Around 2015, with Oregon languishing near the bottom of a number of mental health rankings and the DOJ knocking at the door, some legislators got serious about reform. Senator Sara Gelser held seven town halls throughout the state and produced a report on the barriers to care.

Among other issues, she found patients needed to be nearly suicidal before being taken seriously. They waited months for a diagnosis. They bounced between different therapists.

Mike Morris, the OHA’s behavioral health policy administrator.

The report got Salem’s attention. Committees convened, workgroups materialized, PowerPoints appeared. Legislators reviewed governance and finance (not enough money), workforce issues (not enough doctors and nurses) and standards (not many).

“We looked at for a 21st-century behavioral health system,” says Mike Morris, the Oregon Health Authority’s behavioral health policy administrator, “What do we need to have in place?”

The legislature responded with a wave of new funding and initiatives. Over three long sessions, legislators allocated about $150 million in additional funding for mental healthcare.

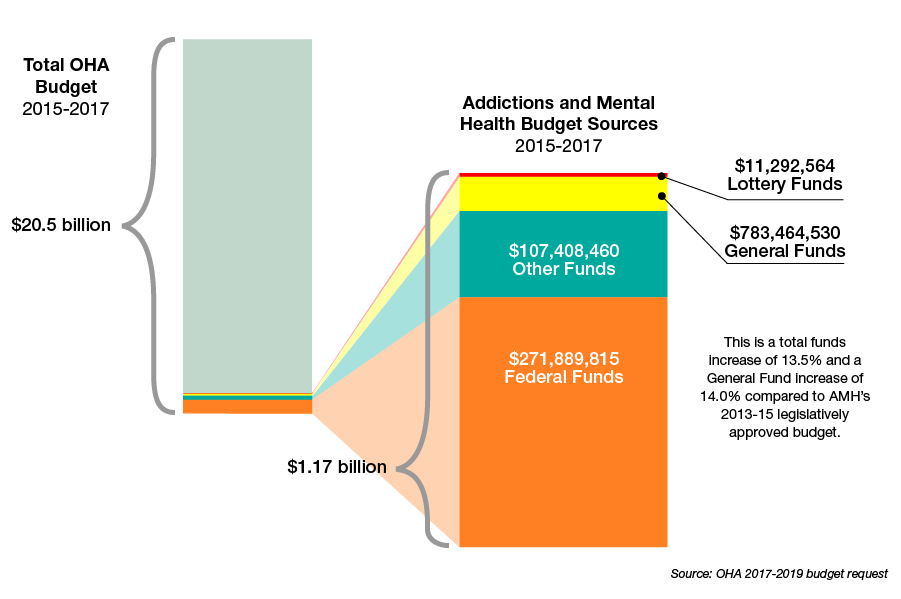

For the 2015-2017 biennium, the legislature approved nearly $1.2 billion for addiction treatment, mental health and capital improvements, a 13.5% increase from the previous budget, and about 6% of the agency’s overall budget.

Money flowed to housing projects and jail diversion services. Beginning in 2015, behavioral health centers opened 70 new outpatient programs and 28 residential programs.

Policymakers also heeded the DOJ’s call for more community-based outpatient services.

With a $500,000 grant, Health Share of Oregon opened Assertive Community Treatment Centers across the state. Teams of mental healthcare professionals cluster around a mentally ill person. Rather than attack the problem with drugs or other medical solutions, they look for outside support. “They try to figure out what these people want that they don’t have,” Wolke says. “Housing, benefits, healthcare.”

Funding became available for mobile crisis response in every county, Morris says. The Marion County Sheriff’s office launched two-person mobile crisis response teams—one mental healthcare professional, one cop. The teams, similar to the Portland police behavioral health unit, debuted in 2013, responded to 524 calls in 2016. Police used force in two cases, and sent 18 people to jail—better than in previous years.

The shining example of Oregon’s new mental healthcare era was the Unity Behavioral Health Clinic, opened in January 2017. OHSU, Kaiser Permanente, Adventist and Legacy Health partnered on the $40 million project. The county stepped in with an additional $3 million.

Unity’s design followed the “Alameda Model.” From a comment responding to one of her op-eds, Meieran learned about the treatment approach, which integrates emergency care, courtrooms, acute inpatient treatment and other services.

She wanted to see it for herself. So she travelled to John George Psychiatric Hospital in Alameda County with administrators from Legacy Health and OHSU.

They couldn’t believe what they saw. Seventy five percent of patients discharged within 24 hours. Zero acts of violence. Zero use of restraints. Meieran says, “We thought: this is going to be too good to be true.”

The funding train rolled on through 2018. Lawmakers allocated an additional $5 million for mental health services. Schools received about $950,000 in the 2018 session for more mental health therapists. Another $900,000 expanded OPAL-K, a psychiatric hotline for kids, into OPAL-A for adults. Senate Bill 1555 diverted a chunk of marijuana tax revenue toward community mental health services.

“I’m extremely grateful for what we have,” Morris says. “Other states have reduced mental health funding and we’ve seen it increase.”

More is needed.

No matter how much funding the legislature throws at mental health, Wolke says, “everybody in the mental health system you talk to says we need more money.”

He agrees, though he adds money alone isn’t enough. The state also needs tougher standards and better communication between providers.

The shortcomings of some well-funded programs advanced in the past few years makes that clear.

When Portland police shot a mentally ill man in a homeless shelter this month, the behavioral health units were out on other calls. The shooting ignited a debate over whether to beef up law enforcement’s mental health response, or eliminate it. City Council candidate Jo Ann Hardesty said she wants to get police out of mental healthcare. One of her opponents in the primary, Felicia Williams, suggested the opposite approach. Add more funding for mobile crisis, so police have resources to deal with the next situation.

The state still squanders too much money on emergency treatment and crisis response, Meieran says. Preventative care is more cost effective.

Behavioral health crisis centers in Multnomah and Marion County still place a heavy emphasis on drug treatment, Renaud says. “They give you a chair and an opportunity to take a pill,” he says. “There’s not much else.”

Flaws also showed up in the Unity model.

In the first seven months of operation, Unity staff faced 500 assaults from patients, according to a report recently released by the Oregon Occupational Health and Safety Administration. Dozens of employees suffered injuries that kept them home from work. OSHA fined the hospital $1,650 for failing to investigate the assaults.

Such a concentrated number of assaults, Renaud says, is “the ultimate thumbs down.”

Employees didn’t report the assaults to management, according to the OSHA report. They thought they would be disciplined, or that nothing would change. They told OSHA they needed more staff, better training on how to handle a “Code Grey” (a life-threating situation), and more equipment, including seclusion rooms and panic buttons (there was only one, at the front desk).

Other staff members quoted in the OSHA report said they weren’t clear on the treatment model. They expressed concern that patients weren’t getting care from physicians soon enough to prevent violent behavior.

The Unity Center for Behavioral Health, opened in 2017.

Unity spokesman Brian Terrett noted the violations concerned paperwork and processes, not safety. “OSHA’s findings did not comment on the safety of our employees and patients at Unity, which continues to be our top priority,” he says. “Legacy Health has cooperated and will continue to fully cooperate with OSHA moving forward, and has already taken steps to prevent collection and review oversights from occurring in the future.”

Meieran says she’s spoken with Unity leadership recently, and they seem serious about making changes. Any significant culture change causes disruption, she says. Violent behavior and overcrowding were problems at John George in its first year of operation.

“This is kind of a part of what happens when you do this kind of innovation,” she says. “It’s a marathon not a sprint.”

Finding solutions

Given the complexity of the mental healthcare system, it’s difficult to figure out what direction to run next.

Meieran, Renaud and Morris have an idea.

If they could get one item on their mental healthcare wishlist, it would be supportive housing. According to the 2013 DOJ report, only about 5% of mental healthcare funding went to this cost-effective solution.

“Bottom line,” Morris says, “we need to get people housed.”

Supportive housing is “the most crucial investment we can make right now as a community,” Meieran says.

That doesn’t just mean affordable housing. Supportive housing includes mental healthcare services in the building, tailored to the needs of residents, and a substance free environment.

“That is the most crucial investment we can make right now as a community,” Meieran says. Supportive housing, she says, is preventative medicine at its best.

Affordable housing and mental health advocates have become frustrated with Portland’s approach to housing the homeless. The Tim Boyle-backed Homer-Williams shelter under the Broadway Bridge? “It’s not permanent housing, it’s not supportive of recovery,” Renaud says. Wapato Jail? “Nobody should be forced to live in a jail.”

Last year the Portland City Council and Multnomah County Commission announced a goal to build 2,000 units in the next decade.

The city and county have spent millions of dollars on supportive housing. Last year the Portland City Council and Multnomah County Commission announced a goal to build 2,000 units in the next decade. The Housing is Health initiative, a partnership with Central City concern, will create another 400 units.

Still, state funding isn’t keeping pace with rising housing costs.

Another challenge is a legal roadblock to building more supportive housing. In its investigation, Morris says, the DOJ told the city it needs more of a specific type of supportive dwelling—integrated housing. In a building of 100 units for example, only 25 can house people with mental illness.

That spooked developers, Morris says, who were expecting state funding for all the units if they housed people with mental illness.

“When we have the funding and services,” Morris says, “we need to get them all connected. It needs to be really clear how and where you access services.”

Transitional housing is another important part of the housing equation. People who leave clinics like Unity need somewhere to go before integrating back into society. In one innovative model, Multnomah County has entered into a long-term lease with a motel on Barbur Boulevard to provide 20 units of transitional housing.

Another policy solution is coordinated care by piecing together the Kafkaesque puzzle of courtrooms, hospitals and clinics. Wolke says the state needs to better regulate the patchwork of mental health departments in different counties. The state needs a rulebook, he says, that requires mental health departments to provide a certain level of care. He says, “we have too many ways to get out of mental health treatment.”

Funding is also siloed. It comes from a bewildering array of sources—Medicaid, federal government block grants and the state legislature—and ends up in different places. “When we have the funding and services,” Morris says, “we need to get them all connected. It needs to be really clear how and where you access services.”

Innovations in medicine

Celia’s delusions started at 15. Wars raged around her. People lost their heads. Touching her hand would cost her $2 million.

In her 20s, she held down a job at a renewable wind energy company for six years. But eventually the delusions worsened. She had to quit.

“When I was at work I thought people were talking about me,” she says. I thought that if I didn’t do certain things my family would be hurt, or that people close to me would be hurt if I didn’t follow specific procedures.”

“When I was at work I thought people were talking about me,” she says. I thought that if I didn’t do certain things my family would be hurt, or that people close to me would be hurt if I didn’t follow specific procedures.”

She moved back in with her parents. She stopped seeing friends. She tried a second job at a receptionists firm, but medication changes forced her to quit. She spent her days battling delusions and sleeping.

Celia (a pseudonym), now 31, finally overcame her illness at Adventist Health’s Emotional Wellness Center.

In traditional mental healthcare, patients visit a therapist for counseling and a doctor for medications. At the Wellness Center, patients take medication, but they also participate in group therapy sessions. They spend plenty of time outside the clinic, at home and work.

Dr. Y Pritham Raj, who oversees the emotional wellness center / courtesy Adventist Health

Dr. Y Pritham Raj, who oversees the emotional wellness center / courtesy Adventist Health

Several Oregon healthcare providers are adopting this holistic approach. Doctors hope it could cut costs and remove the stigma associated with psychiatric treatment.

“It’s how do we marry matters of the brain,” says the Wellness Center’s director, Dr. Y. Pritham Raj, “with matters of the body?”

That’s the key question now for physicians, says Liang. “We want to pull in our colleagues from down the hall to talk to you,” he says, “not send you off to some separate mental health facility.”

Clinics across the state, Morris says, are seeking holistic treatment models. Twelve Oregon clinics are participating in a federal program to demonstrate the quality of their mental health services. In return, they get an enhanced match to Medicaid funding. Some added an exam room for physicals. Others offer 24-hour primary care. A Burns clinic, Morris says, added mental health evaluations to the physicals it offers at the county fair.

“It’s how do we marry matters of the brain,” says the center’s director, Dr. Y. Pritham Raj, “with matters of the body?”

In a sea of ineffective treatment approaches, Bouneff says, these holistic care models are the “islands where good work is happening.”

They also have a history in Oregon, which has earned national recognition as a leader in healthcare reform. In 2012, Oregon debuted coordinated care organizations, a cost-effective way to deliver Medicaid to 1 million low-income patients.

For years, mental healthcare lagged behind. But beginning in 2015, Oregon has ramped up funding and innovation in the area of coordinated care. A letter resolving the DOJ investigation applauded the expansion of peer-delivered services, jail diversion programs and Assertive Community Treatment services. The Emotional Wellness Center and Unity opened in 2017.

“We want to pull in our colleagues from down the hall to talk to you,” Liang says, “not send you off to some separate mental health facility.”

Liang says Oregon can take a cue from other states, especially when it comes to training doctors. In Washington, physicians must complete a mandatory suicide prevention module to receive their license. There’s no comparable requirement in Oregon.

Technology also plays a role in expanding access. Liang offers virtual sessions to teens via iPhone or webcam. Kaiser has developed a computer-assisted self-help tool called Mood Helper. These distance therapy sessions, Liang says, are just as effective as in-person care, and could serve as cost-effective outreach to underserved rural communities.

Another high-tech innovation that shows promise is Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. The noninvasive treatment targets resistant depression. Physicians wave a magnet over a patient’s head to stimulate nerve cells. Both the Emotional Wellness Center and Kaiser are testing the technology.

Yet the most effective solutions, Liang says, are the simplest. Small preventative changes in daily behavior can save thousands in emergency treatment down the road.

Liang advocates for expanding mindfulness curricula in health and P.E. classes. He teaches teens to meditate for a few minutes each day using apps like Calm. Smart investments in mental healthcare, as he puts it, are “skills, not pills.”

The Emotional Wellness Center still puts plenty of stock in pills. That’s what cured Celia. Her turning point came after Raj put her on a new medication, clozapine. At first Celia was skeptical of taking clozapine, which was banned in the 1980s for its harsh side effects. When she first tried it she got nauseated, blacked out and went to the emergency room.

But Dr. Raj convinced her to go back on.

This time it worked. Celicia improved enough to leave the Wellness Center. She transitioned to an outside therapist and started looking for part-time work.

But Raj also promotes preventative outpatient care. A night at the Wellness Center costs somewhere around $500, Raj says, about half the cost of a hospital bed across the street.

“The whole idea is we want to prevent hospitalizations,” he says. “Patients are struggling but they certainly don’t want to go to the hospital. They’d rather stay home where their support lies.”

“The whole idea is we want to prevent hospitalizations,” Raj says. “Patients are struggling but they certainly don’t want to go to the hospital.”

After years of crisis, the state’s mental health networks are coalescing around new and proven support systems. Whether Oregon can leverage momentum to continue on that course remains to be seen. “We need to be approaching things upstream,” Meieran says. “But we’re throwing money at our ERs. We’re throwing money at our jails.”

Correction: The original version of this article stated that Unity was opened with a $50 million investment and it opened in 2016. It was actually $40 million, and the hospital opened in 2017.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.