BY APRIL STREETER

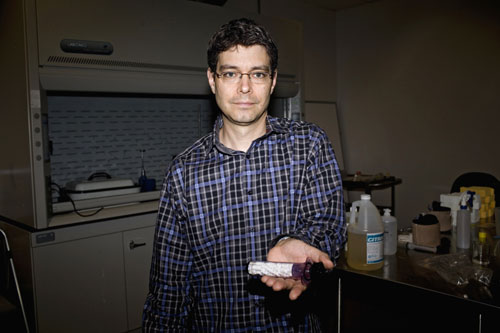

Founded by CEO Andrew Barofsky, 43, and serial biomedical entrepreneur Dr. Ken Gregory, 59, in 2009, RevMedx is gearing up for a busy fifth year.

BY APRIL STREETER | PHOTOS BY CARL KIILSGAARD

BY APRIL STREETER | PHOTOS BY CARL KIILSGAARD

There is a scene in the 2001 movie Black Hawk Down illustrating a problem that needlessly kills during war. An Army corporal takes a bullet deep in his femoral artery, and frantic medics can’t staunch bleeding from the retracted artery in time to save him. That scene, depicting the real-life Ranger James “Jamie” E. Smith’s fight for life during the battle of Mogadishu in 1993, is part of the impetus for the U.S. military’s funding for non-compressible hemorrhage research: Up to 25% of battlefield casualties can die by bleeding out. It’s the problem RevMedx is helping to solve.

With offices in an indistinct row of warehouses on Southwest Canyon Road in Wilsonville, RevMedx is a company of just nine employees, yet with a big mission: to create life-saving tools for trauma medics, who are the first responders when medical care is urgent on battlefields, at accident scenes and during disasters.

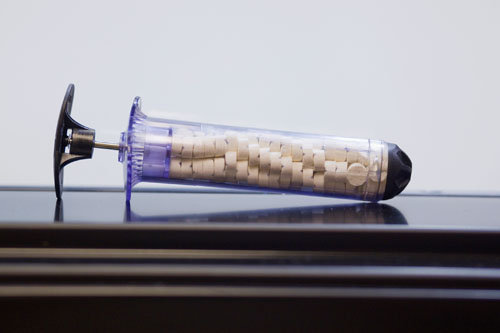

Founded by CEO Andrew Barofsky, 43, and serial biomedical entrepreneur Dr. Ken Gregory, 59, in 2009, RevMedx is gearing up for a busy fifth year: Its award-garnering device XStat, an oversize syringe stuffed with tiny pill-shaped sponges designed to stop life-threatening bleeding on hard-to-get-to wounds, just received FDA approval and should ship later this year.

“RevMedx has been involved in hemorrhage-control research with the Department of Defense for a number of years,” Barofsky notes. “The U.S. military’s Special Operations Command came to Ken; they had some money set aside to work on noncompressible hemorrhage, where you have a site of bleeding deep in the body and it is hard to use traditional means to stop it.”

Barofsky, a University of Oregon graduate, had worked with RevMedx co-founder Gregory earlier at the Oregon Medical Laser Center, and later with him also formed the Oregon Biomedical Engineering Institute to bootstrap medical innovation companies. With an earlier company, HemCon, Gregory had created an innovative wound dressing that contained a special clotting agent called chitosan, made from shrimp shells, to halt bleeding more quickly. HemCon went bankrupt, however, after losing a patent-infringement suit around chitosan to another company.

Barofsky, a University of Oregon graduate, had worked with RevMedx co-founder Gregory earlier at the Oregon Medical Laser Center, and later with him also formed the Oregon Biomedical Engineering Institute to bootstrap medical innovation companies. With an earlier company, HemCon, Gregory had created an innovative wound dressing that contained a special clotting agent called chitosan, made from shrimp shells, to halt bleeding more quickly. HemCon went bankrupt, however, after losing a patent-infringement suit around chitosan to another company.

With the DOD’s $5 million in seed money, RevMedx plunged into researching hemorrhage control of noncompressible wounds, which generally occur deep in the torso. The military, Barfosky says, had envisioned some kind of foam in a can — like the Fix-A-Flat canisters that aid drivers — that could be sprayed into the body and expand to mimic compression and would stop bleeding.

RevMedx didn’t get far with the foam idea. In fact, the company was a bit stumped until Gregory, after a trip to a Williams-Sonoma kitchen store, recommended the group look at expandable sponges that pop open when exposed to moisture.

“We started working with a group of student engineers at Harvey Mudd College, making the sponges even smaller and biocompatible,” says Barofsky, “and frankly, that was the proverbial light bulb. The applicator we came up with to inject the sponges into noncompressible wounds worked fantastically well.”

Looking like a giant syringe, XStat’s applicator holds 92 tiny cellulose sponges treated with the chitosan-based clotting agent; each sponge is also embedded with a tiny string to show up on x-ray. XStat is pressed directly into a wound, and once the plunger is engaged, the sponges immediately expand, creating their own internal compression.

Sure from internal testing that XStat was viable, RevMedx worked with the FDA to expedite fast-track approval.

While Gregory was, and is, an inveterate medical inventor — “a renaissance man” — according to Barofsky, Barofsky himself had taken a different career track after his work with OMLC. Moving to Boston, Barofsky studied law and business at Boston College, earning an M.B.A and a J.D. in 2002. He practiced corporate law at Testa, Hurwitz & Thibeault before coming back to Oregon with Schwabe Williamson & Wyatt to join its nanotechnology and microtechnology group.

While Gregory was, and is, an inveterate medical inventor — “a renaissance man” — according to Barofsky, Barofsky himself had taken a different career track after his work with OMLC. Moving to Boston, Barofsky studied law and business at Boston College, earning an M.B.A and a J.D. in 2002. He practiced corporate law at Testa, Hurwitz & Thibeault before coming back to Oregon with Schwabe Williamson & Wyatt to join its nanotechnology and microtechnology group.

Thus he was ready to begin dealing with the challenges of commercializing innovative technology. In addition to the DOD seed money, RevMedx also had a secret strength: former Army medic John Steinbaugh, who served more than a dozen active missions as a medic before he retired. For Steinbaugh, RevMedx’s mission is personal: He’s designing the products for trauma medics, many of them friends and acquaintances still in the field.

“I feel like I’m developing products for guys I actually know, to use in combat,” says Steinbaugh, the company’s director of development. “Everything we make must never fail.”

Barofsky says the process of getting FDA approval is a good way to gain experience in setting up an effective quality-management system. “The super-exciting is the new idea, that moment of running out of the lab and saying, ‘It works!’ Then it is roll up the sleeves, get down to drafting the paperwork and dig in — and those aren’t activities the government is typically going to fund. So a lot of companies have to go out and find funding.”

That is the point in time when many young companies find themselves suddenly in a “Valley of Death” as they try to move toward commercialization. Barofsky says RevMedx’s “disciplined” quality-management system, which was designed with an eye toward manufacturing, gives the company a better fighting chance. It also helps that the U.S. military is eager, and RevMedx is currently negotiating a contract for first sale of the XStat devices.

Barofsky’s second “secret weapon” is the fact that RevMedx has created five other trauma medical products while it has worked on the original XStat: a narrower version of the expanding-sponge syringe called XStat-12, as well as XGauze (gauze embedded with the sponges); AirWrap, a blow-up compression device for limbs; TX Tourniquets; and the SharkBite Trauma Kit. Apart from the XStat-12, all of these will be available this year. In addition, RevMedx is putting the finishing touches on a not-yet-named lightweight pelvic belt created to help with the difficult trauma problem of safely transporting patients with pelvic injuries.

At the Wilsonville office location, RevMedx is building a 1,000-square-foot clean-manufacturing facility that should be able to turn out hundreds of XStat devices per month.

“XStat is a first-in-its-kind medical device that is going to be paradigm shifting in how certain types of bleeding wounds are treated,” Barofsky says. “There will be a day when this is a standard in every medic’s aid bag, and we’re looking forward to the day that somebody’s life is saved because of it.”