For nearly 200 years, Willamette Falls was a hub for industrial production — and a major dam. But for 15,000 years before that, Northwest tribes used the site for fishing and ceremonial activities. Now tribes have a say in its future.

“Oregon statehood began here,” Gov. Kate Brown said, standing on the site of the former Blue Heron Paper Mill in 2015. “The falls are the true end of the Oregon Trail. John McLoughlin made his home here. We milled wool and paper and fed our families for more than a hundred years. This amazing place was the birth of industry in the West and the site of the first long-distance power transmission in the world.”

Gov. Brown was celebrating the recent announcement of the design team for the Willamette Falls Riverwalk, which would reconnect Oregon City with Willamette Falls — the largest waterfall by volume in the Pacific Northwest and the 17th widest in the world. The governor’s remarks recalled the industrial achievements at the falls that powered not only settlement of Oregon but, as with the first long-distance transmission of electric power in the world between Oregon City and Portland, the modern technology that drives our world today.

The Blue Heron Paper Mill site that is slated for redevelopment by the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde appears in the center of the photo. Jason E. Kaplan

The Blue Heron Paper Mill site that is slated for redevelopment by the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde appears in the center of the photo. Jason E. Kaplan

Yet despite its natural beauty and the technical marvels it fueled through hydropower, it is virtually unknown to most Oregonians —largely because the area has been privately owned and under industrial use for years. But in 2011, the last mill to operate at the site shuttered, and this past September the building, which had sat vacant for 10 years, was demolished.

And now Oregon tribes have a say in the future of the site. The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde purchased the property in 2019, and in August the Willamette Falls Legacy Project announced that four other tribal governments — the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs — would be partners in the project.

The timing of that decision is remarkable. Shortly after the Blue Heron Paper Mill closed in 2011, four local governments formed a joint endeavor — called the Willamette Falls Legacy Project — to conduct a comprehensive study for the future of the site.

Gov. Brown described the partnership as an example of what she called “the Oregon way” that includes Oregonians of “all walks of life.” A 2014 memorandum of understanding includes the four entities — the State of Oregon, the City of Oregon City, Clackamas County and Oregon Metro — but not the people who inhabited the area for 15,000 years. Nor were they mentioned in media coverage describing the abandoned mill as an eyesore and describing plans for an upcoming riverwalk where people would gain a sense of the site’s history as “the birthplace of Oregon.”

The goal spelled out in the 2014 agreement was to raise tens of millions of dollars to redevelop the property. (In 2018 Oregon Business reported on the proposed riverwalk, then estimated to cost $60 million.) The idea was to restore habitat and spur the local economy: Local governments previously estimated it would bring in $2.3 million in annual tax revenue for Oregon City and Clackamas County and $14 million in annual spending from visitors — and 1,480 permanent full-time jobs when construction is complete.

Since tribes weren’t included in the previous planning documents for the riverwalk, it is likely the purchase of the property by the Grande Ronde confederation — which includes descendants of the Charcowah village of the Clowewalla (Willamette band of Tumwaters) and the Kosh-huk-shix Village of Clackamas people — came as a surprise. According to writings by David Gene Lewis, a member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and assistant professor of anthropology and ethnic studies at Oregon State University, the Clackamas controlled access to salmon and other fish at the falls, and tribes throughout the region visited to request fishing rights. (The name “Willamette,” despite its spelling, is not French but is derived from Walamt, the name Indigenous people used for the river; Tumwata is Chinook jargon for “waterfall.”)

David Gene Lewis, a member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and assistant professor of anthropology and ethnic studies at Oregon State University. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

David Gene Lewis, a member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and assistant professor of anthropology and ethnic studies at Oregon State University. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

In 1856, Lewis writes, members of Western Oregon tribes were forcibly removed from the area around Oregon City and marched to the Grand Ronde Reservation, about 60 miles away from the waterfall.

“This is a historic day for the Grand Ronde Tribe and our people,” Grand Ronde Tribal Chairwoman Cheryle A. Kennedy is quoted saying in “Visioning for Blue Heron,” a recent tribal redevelopment report. “Since 1855, the government has worked to disconnect our people from our homelands. Today we’re reclaiming a piece of those lands and resurrecting our role as caretakers to Willamette Falls — a responsibility left to us by our ancestors.”

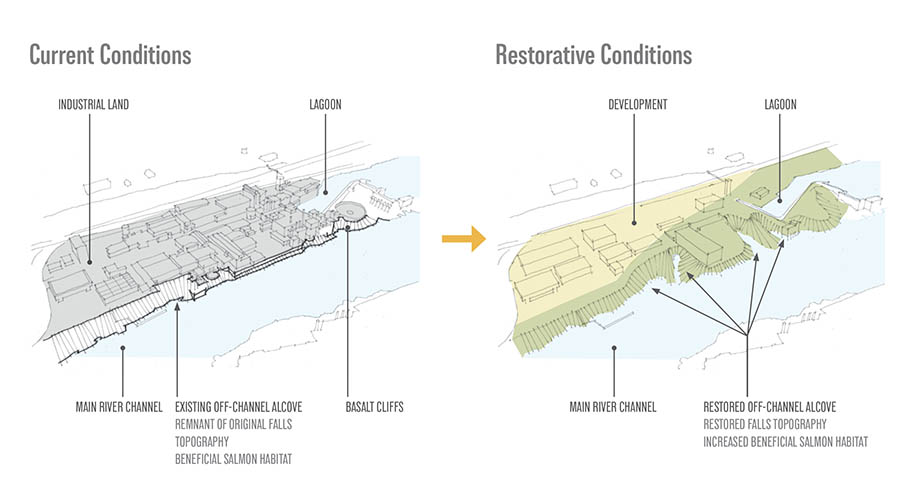

The tribe has commissioned new plans for the site, designed by Portland-based GBD Architects and landscape architects Walker | Macy, and they differ in some respects from the plans unveiled by the Willamette Falls Legacy Project in 2017. Both the tribe and WFLP have centered the need for access to the natural beauty and wonder of the falls, environmental restoration, and cleanup. The 2017 plans focus on the natural wonder and the industrial pioneer history of the site, including preservation of buildings in the area. In the tribe’s plans, most of these buildings are swept away, and a section is reserved for tribal ceremonial activities.

Renderings from “Visioning for Blue Heron,” March 2021, by GBD Architects and Walker | Macy

According to Andrew Mason, the executive director of the Willamette Falls Trust — a nonprofit formed in 2015 to raise funds and “curate collective vision” for the falls — the focus has shifted from “the pioneer story, the industrial story, the environmental story.”

He noted this history is already being covered “by other Oregon City institutions like the End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center and the Museum of the Oregon Territory just up the hill from the site, and so the opportunity here really was about telling the Indigenous stories.”

“City leaders were just talking about, like, heritage tourism activities,” says Lewis. “And we began saying, wait a minute. You know, we really are stewards of this land. We really care about the land itself.”

Four other tribes with historical connections to the falls (Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Yakama Nation, Warm Springs Tribe and the Siletz) have representatives on the Willamette Falls Trust’s tribal advisory board, but Grand Ronde formally withdrew in April.

In 2018 Warms Springs and Umatilla tribal leaders contested Grand Ronde’s right to construct a fishing platform by the Falls. And as of late November, the Riverwalk project’s $12.5 million in Oregon Lottery-backed bonds are in jeopardy due to delays on the project. Oregon City staff had approved the Umatilla’s request for a memorial to the Cayuse Five, who were accused of murdering white missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and 12 others and, after a hasty trial in 1850, hanged near Willamette Falls and buried in unmarked graves. But city leaders failed to consult with Grand Ronde leaders, who say the area was a historic burial site for their ancestors.

It remains yet another reminder of how little Grand Ronde’s history has played in city or metro planning, at least until the tribe could buy themselves a seat at the table in their homelands.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misstated the year Warms Springs and Umatilla tribal leaders contested the Grand Ronde’s right to build a fishing platform. Oregon Business regrets the error.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.