BY ROBERT MULLIN

A new energy-sharing agreement sparks concerns about independence and collaboration in the region’s utility industry.

BY ROBERT MULLIN

A new energy-sharing agreement sparks concerns about independence and collaboration in the region’s utility industry

Last November Portland-based PacifiCorp flipped the switch on a project that integrates the utility’s power scheduling and trading activities with those of California’s grid operator, the California Independent System Operator (CAISO).

The partnership extends California’s short-term electricity market into PacifiCorp’s transmission network spanning six states, including Oregon. The upshot: Both entities can monitor each other’s service territories, drawing on a deeper pool of standby generation to cover needs. When short-term discrepancies between supply and demand arise, the centralized market automatically dispatches energy from the cheapest generating source to maintain balance across the system.

This all sounds wonky — and it is. It becomes even more so when you consider how this seemingly benign development is cutting across the interests of a traditionally collaborative Northwest power industry.

This all sounds wonky — and it is. It becomes even more so when you consider how this seemingly benign development is cutting across the interests of a traditionally collaborative Northwest power industry.

Supporters include utilities sitting on surplus generation — like PacifiCorp — and wind-energy companies, who argue the system reduces costs for ratepayers through more efficient use of resources, including renewables. These companies also benefit from increased access to the massive — and higher-priced — California market.

Who are the critics? Most of the region’s publicly owned utilities, who worry the system could compromise regional independence and the value of the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) hydroelectric system on which they rely.

The speed of the new system, called EIM — energy imbalance market — is the key to its appeal. The market automates scheduling and dispatch of energy at intervals as short as five minutes before delivery — otherwise known as “intra-hour” transfers. Until recently, energy transmitted across neighboring networks had to be scheduled an hour in advance, which was problematic for variable-generating resources like wind farms, whose output can be difficult to forecast.

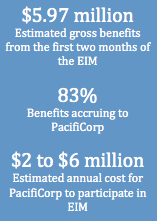

For PacifiCorp, the benefits of the EIM are clear: The company estimates a financial benefit of at least $4.73 million during the first two months of the market’s operation. The revenue came from increased exports and decreased costs for dispatch within PacifiCorp’s own territories.

“There were effectively no intra-hour transfers between PacifiCorp and CAISO before the commencement of the EIM,” says Bob Gravely, senior public affairs specialist with PacifiCorp. Those transfers ramped up significantly in the market’s initial months, when PacifiCorp exported more than 180,000 megawatt-hours of energy to California.

PacifiCorp touts another success: reduced need to curtail renewable generation when supply outpaces local demand. It’s an issue, that in the past, put the BPA at odds with wind generators since the agency was forced to shut down turbines during periods when high hydroelectric flows corresponded with strong winds.

This point explains why Iberdrola Renewables is taking steps to link its Northwest wind fleet with the EIM. Doing so effectively means seceding from the territory managed by BPA, where the company operates nearly 1,400 megawatts of wind capacity.

“Like any market participant, Iberdrola Renewables likely would benefit from access to a deeper pool of imbalance resources,” says Kevin Lynch, Iberdrola’s head of external affairs. Lynch sits on a CAISO committee appointed to guide the EIM’s development, including devising a corporate structure attractive to potential members throughout the West. Notably, that 11-member committee contains no representatives from publicly owned utilities — in either California or the Northwest.

That could prove an impediment to expanding the market in the Northwest, where numerous public utilities are loath to sign up to any centralized market, let alone one based in California.

That reluctance is rooted in part in a history of independence. While BPA and the region’s public utilities are not subject to oversight by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), centralized markets like the EIM are. Participating in such a market also means submitting the region’s generation to a complex set of federal regulations that skeptics say are a poor fit for the Northwest’s particular resource mix.

“We have seen many — Robert McCullough, _________________________ |

| “The purpose of retaining — Scott Corwin, |

| _________________________ “The flow of energy for the — Bob Gravely, PacifiCorp |

“Over the last 20 years, FERC has not uniformly produced market policies that would protect the value of the federal hydroelectric generation for this region,” says Scott Corwin, executive director of the Public Power Council, an advocate for Northwest consumer-owned utilities.

Other skeptics question the payoff of the EIM for a region that already enjoys some of the lowest electricity prices in the country.

“The upbeat explanation [for supporting the EIM] is that we are trying to find efficiencies in the electric system by driving just a bit closer to the edge of our headlights,” says Robert McCullough, a Portland energy economist who closely follows centralized markets. “At the moment we are overly cautious.”

“The reality is that the current market structure is so much more competitive than California’s that it requires a lot of influence to agree to a high-overhead/low-efficiency alternative,” says McCullough, questioning the administrative costs of the EIM. That influence is taking the form of pressure from state regulators across the West. Last year Oregon’s utility commission asked Portland General Electric to evaluate the benefits of joining the EIM as part of the company’s broader planning process.

Momentum is building outside the state as well. In March, Washington’s Puget Sound Energy announced plans to join the market. Other utilities in the region are bound to follow. The long-term cost implications for ratepayers is not clear. More evident is that the expansion of the EIM will have to come at the expense of the Northwest power industry’s independence and regionally minded cooperation.