In July an Oregon law went into effect allowing student athletes to be compensated for their name, image and likeness. Now the student athlete is becoming the student entrepreneur — and college sports will never be the same.

Part 1: The Joke

At 10:35 on the night of June 30, Ian Karmel sent a tweet. College sports was 85 minutes away from starting the new era of “Name Image Likeness,” (NIL), and the Portland-bred comedian was ready to ensure his alma mater wasn’t left behind.

“Alright, I’ll open this thing up,” Karmel posted to his 75,000-plus Twitter followers. “I’ll pay any Portland State cross-country runner $50 to wear a T-shirt with my face on it around campus.”

By morning he had a taker.

“Deal,” responded Kelly Shedd, a sophomore studying business administration. By the end of the day, two more Vikings runners — Brandon Hippe and Drew Seidel — had also joined the Twitter thread.

Alas: As of this writing, the three PSU athletes are neither $50 richer nor in possession of a brand-new T-shirt. Because, of course, Karmel’s tweet was just a bit.

And yet: You can’t have comedy without saying something true.

And at that moment Karmel posted his tweet, even joking about the exchange of money, goods or services with college players — be they a walk-on cross country runner, like Shedd, or a nationally known college-football star, like Oregon defensive end Kayvon Thibodeaux — could land everyone in trouble with the National Collegiate Athletics Association. So it had been for more than 60 years.

But no longer.

On July 1 Oregon became one of 14 states to enact Name Image Likeness legislation; by mid-October, that number had doubled. Senate Bill 5 took effect the day after the NCAA suspended its existing NIL rules, both in anticipation of the new state laws and in response to being on the wrong end of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 9-0 decision in the case of National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston, which found the organization’s restrictions on athlete benefits and compensation were in violation of federal antitrust laws.

Student athletes could now make money, enter into business arrangements, and consult with lawyers and agents, albeit just for NIL deals; talking to or getting an agent to turn professional remains a separate process.

What’s emerged in the wake of the new law is something of a free-for-all, leaving students, universities and businesses to navigate the new reality of NIL on the fly. The phrase “Wild West” comes up a lot in interviews with stakeholders.

“It’s been a challenge, because there is no federal guidance, nor is there much NCAA guidance,” says Oregon State athletic director Scott Barnes. Schools are tasked with ensuring any deals students make fall under state law. “Many states are left on their own, and many universities are left alone to develop guidelines and policy.”

“This NIL issue is going to affect everyone,” says former University of Oregon Ducks offensive lineman Max Forer, who is now a lawyer with Portland firm Miller Nash. “A $14 billion industry is going to be opened up where it has never been before.”

For most observers of college sports, the change is long overdue.

The term “student athlete” was coined by the NCAA’s first executive director, Walter Byers, in part to obfuscate the fact that college sports has always been a business. But even Byers couldn’t have imagined today’s environment of national TV deals, sponsorships, and well-heeled donors and season ticketholders.

Now students are free not just to joke about deals online but to make them — to hustle on the court and engage in profitable side hustles too. The student athlete is, in real time, morphing into something new: the student entrepreneur.

Part 2: The Players and the Game

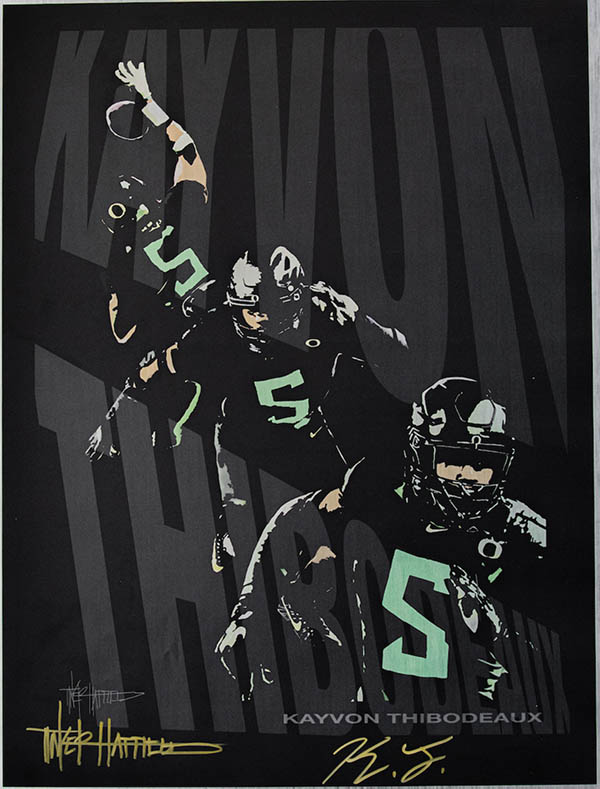

One poster boy has emerged for NIL in Oregon in the first months since the rule changed: Kayvon Thibodeaux. But instead of a poster, there’s a non-fungible token (NFT) work of art, made in collaboration with Nike founder Phil Knight and Tinker Hatfield, the celebrated designer of multiple Air Jordan models.

An NFT is a string of data that can’t easily be reproduced, and NFT images have fetched top dollar in recent months; think of them as the digital equivalent of paying hundreds of thousands of dollars for an autographed baseball card. According to Hatfield, Thibodeaux is the owner of “Kayvon’s Trilogy” — an iPad illustration of the Ducks star — but anyone can purchase copies of it using the cryptocurrency Ethereum (current price at press time: .045, or $173.10). As of mid-October, 123 people had downloaded the image. (In July Hatfield told Complex he personally gets 12.5% of each download and UO gets 10%, with Thibodeaux getting the rest. In the interview, he stressed that Nike was not part of the deal.)

The signed, print version of Tinker Hatfield’s NFT of Kayvon Thibodeaux

The signed, print version of Tinker Hatfield’s NFT of Kayvon Thibodeaux

It was the first of several big-deal NIL deals for the defensive wrecking ball. Thibodeaux’s season has been slowed by both injury and suspension — he missed three of the Ducks’ first four games, then got ejected from another due to a targeting penalty, costing him another half the next week — but he remains unstoppable both on the field and in the NIL space. A Heisman Trophy candidate who also has a good chance of being selected first overall in the 2022 National Football League draft, Thibodeaux has since launched his own cryptocurrency ($JREAM), and has inked deals with United Airlines (to promote direct flights from Eugene to select locations for Ducks away games) and eBay (to sell a physical version of Hatfield’s art piece).

Oregon women’s basketball forward Sedona Prince is both a star player and an online star: The 6’7” redshirt junior is well on her way to 3 million TikTok fans. It was Prince who brought to light the inequality of the 2021 COVID-altered NCAA basketball tournaments, where the women in San Antonio had shockingly bare-bones fitness equipment while the men in Indiana had a fully equipped gym. Prince’s viral video shamed the NCAA into action, and several other reforms — including finally letting the women’s tournament share in the “March Madness” brand — followed. In 2020 Prince joined a class-action lawsuit challenging the NCAA’s NIL restrictions, and she is still seeking back pay for the years she was unable to monetize her image.

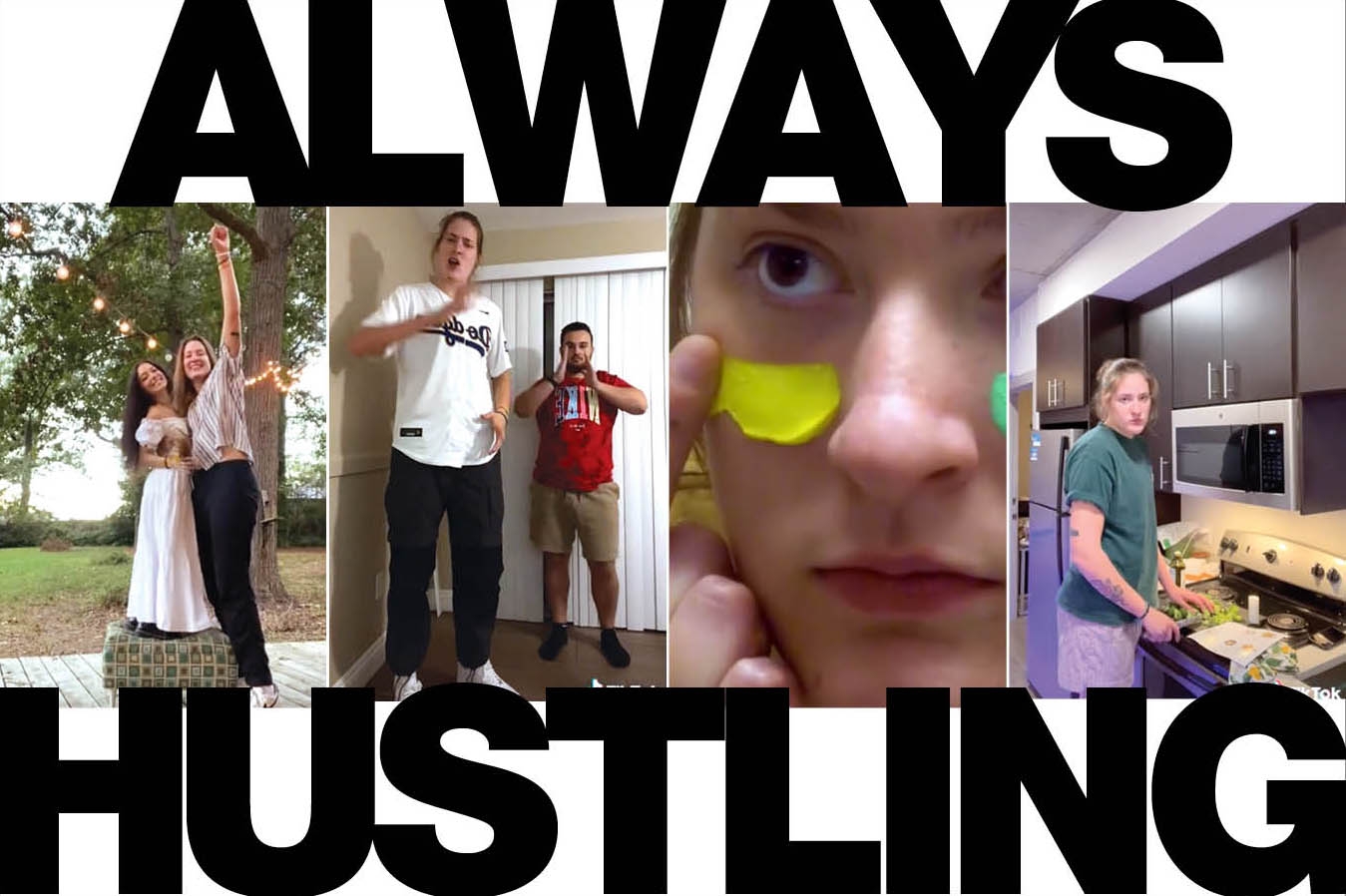

Screenshots from UO basketball forward Sedona Prince’s TikTok

Screenshots from UO basketball forward Sedona Prince’s TikTok

Prince’s online presence is a real reflection of who she is; it’s also not an accident. A year ago she had just 70,000 followers, but then she met fellow Oregon student Ryan Ballis at a party. Ballis, who is studying advertising with minors in sports business and entrepreneurship, told her he could help her out with social media.

“You’ll never really see her put on a face to please anyone,” says Ballis. “She’s always Sedona Prince. What you see on TikTok, like, her being a goofball and being a goon, that’s Sedona on a regular basis. And so that’s definitely something that we try to emphasize through all aspects of her brand.”

Recent videos include clips of Prince cooking, part of what she describes as “my healing journey with food,” and staging a “fake gay wedding” with her girlfriend, Rylee, who is less than 5 feet tall. Another includes a “gear haul” — all UO gear — and a video of Prince in front of a waterfall synced to music.

Prince and Ballis also run the account like professional social media managers, mindful of frequency and timing of posts, as well as engagement. And now the account includes content that would likely have been off-limits just a few months ago.

“From painting my face to practicing to practicing chants, nothing truly gets me ready for the game like Taco Bell,” she says in another, slicker, heavily edited video that’s just seconds long. It was posted in early October and is hashtagged #Ad.

For someone like Ballis, starting his marketing career at the dawn of the NIL era is like working on the first Wieden + Kennedy Nike campaign, or for Facebook in Year 1. He’s also now a registered player-agent in the state of Oregon, which means he can not only work on NIL and marketing deals but also be involved in potential professional contracts.

Ryan Ballis, an advertising major at UO, who manages Sedona Prince. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Ryan Ballis, an advertising major at UO, who manages Sedona Prince. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

When NIL went into effect, Prince and Ballis were ready, having begun working on a line of limited-edition “SP” merchandise that dropped in October. This is merch for Prince and Prince only; she can’t use Oregon’s logo or exact colors. For a short period, Prince was also among the celebrities offering custom videos on Cameo, but as this issue went to press, her Cameo account was not available for bookings.

Whitney Wagoner, the director of UO’s Warsaw Sports Marketing Center, notes that in addition to more corporate deals, online opportunities and the ability to get paid to teach at (or run their own) sports camps, players can now offer fans the opportunity to have them come to a kid’s birthday party. A track and field nut might be willing to pay for the chance to run Pre’s Trail in Eugene with a member of the UO track and field team.

And students can now benefit financially from their outside interests. Before, if you were a linebacker who was also a singer-songwriter, you couldn’t just go down to the local club and play an open mic for tips. If you were into woodworking and carpentry, you still couldn’t sell your furniture. A theater student could always get paid to be in a play while still attending school, but the rules for athletes were different.

Some athletes are getting paid by a company called Yoke Sports to do nothing more than game online, using their platform. Others simply have “Barstool Athlete” on their social media profile, meaning they’ve been paid to plug the controversial media company Barstool Sports.. That controversy is twofold: The company and its fans have a track record of misogyny, and they are also in the sports-gambling business (with Penn National Gaming owning a majority stake in the company), which means it’s possible some state laws will prohibit college athletes from working with them (only the lawsuits will decide for sure). Ballis says he won’t work with Barstool, period.

Both Oregon (EMERGE) and Oregon State (expOSUre) have hybrid support, education and business programs involving NIL, both of which were in the works long before the law passed. At Oregon State, business professor Colleen Bee is actually teaching an NIL seminar this fall called “Making the Most of Your Name, Image and Likeness” — explaining the law and compliance, as well as sales, marketing, social media, contracts and tax implications. There are guest speakers like former Oregon State/NFL player Steven Jackson, and a final project in which each student builds their brand or business — though some students may already be doing that. Both schools also work with two of the many multifaceted NIL companies that have popped up — Altius Sports Partners for Oregon and Opendorse for Oregon State. Schools can’t directly work with these students or companies on deals, but they can be a resource for them.

In addition to Thibodeaux’s NFT project, Phil Knight has also formed a private company called Division Street to develop and assist with NIL opportunities exclusively for University of Oregon athletes. It is stacked with former Nike executives and UO donors, including Rosemary St. Clair, former VP and GM of Nike Women, as well as Rudy Chapa, who has served as Nike’s VP of sports marketing. Division Street will also work directly with Warsaw.

“Right now it sort of feels like the floodgates are open, and everyone’s rushing in,” says Wagoner. “I’m interested to see how the market comes to a corrected space, because at the end of the day, these are investments, right? At some point, and I think sooner than later, you’re going to have to show some returns for these activities. Brands in particular will invest where it works and not where it doesn’t.”

Of course, that ROI can also be intangible, especially on a smaller scale. It can be about brand association as much as sales, or even just a monetized expression of fan passion. The guy who owns a local barbecue joint or car-repair business, owns season tickets, donates money to the university and buys all of that Nike or adidas merch an also throw a player money. In some cases, it might not even matter if it drives more business.

“The key is really getting to know who those student athletes are,” says Wagoner, “what makes them unique. Who are they as people? What are interesting elements about their life, their skills, things they like to do? Talents they have? What are their passions, even off the field of play? And what kind of fun, interesting opportunities are there to tap into those things?”

As a high school player who scored a touchdown in an international all-star game, Portland State offensive lineman John Krahn could have capitalized on the attention he got then. At 6’10”, 395 lbs., Krahn stands out for more than his athleticism.

Portland State University offensive lineman John Krahn (above center and inset). Photos: Jason E. Kaplan

Portland State University offensive lineman John Krahn (above center and inset). Photos: Jason E. Kaplan

Now a senior on track to graduate in December, Krahn wasn’t expecting to make any NIL deals. Then World Wrestling Entertainment emailed one of his coaches.

The WWE has already signed an NIL deal with 2020 Olympics gold medalist Gable Steveson, who’s still a student at the University of Iowa. The organization is also cultivating a small stable of football players who might fit with the company.

Being a “big person,” as he puts it, Krahn was always told he could end up either in the NFL or the world of pro wrestling, but he didn’t know how to get into the business. But now he’s made an NIL deal with WWE.

For now it’s really just another social media/marketing relationship. “Basically, they just want to get to know me,” Krahn says.

But it could also lead to him actually trying out and training to be a pro wrestler.

“The WWE is a very different thing [than other NIL deals],” he says. “I mean, this could very possibly be a career.”

Part 3: The Next Play

To prepare for the future, you have to understand the past — and why advocates have been fighting for years to get compensation for college athletes.

The NCAA’s insistence that its players be amateurs has its roots in a gruesome incident on a Texas football field in 1955, when a man named Ray Dennison died shortly after his helmet collided with another player’s knee.

When his widow sought workers’ compensation, NCAA director Walter Byers met with a legal team and immediately directed schools to use the phrase “student athlete” in their materials for students — and to add clauses to scholarship offers specifying that athletes remain amateurs. The idea was to rapidly do away with any notion that college athletes were employees who might then deserve compensation after injury.

It worked. The NCAA not only beat Dennison’s widow in court but prevailed in the court of public opinion for decades. In 1994, for example, when eight Florida State players were investigated for participating in a $6,000 shopping spree sponsored by an unregistered agent, critics branded the school “Free Shoes University.”

But in 2011, when media reported that Texas A&M quarterback Johnny Manziel had been paid for autographs, he was suspended from the team, but the public response was a collective shrug. (Manziel admitted in June of this year that he made “a pretty decent living” signing autographs for thousands of dollars a pop.)

And while the move toward NIL has been in the works for years, it’s notable that it finally happened amid intensified conversations about race and income inequality.

“College athletes participating in sports with a high percentage of Black individuals are the economic driving force in the multi-billion-dollar college sports industry,” said the athletes of Dam Change, a group formed by OSU athletes — including football player Jaydon Grant and women’s soccer player Madison Ellsworth — last year to draw attention to racism and inequality, in their SB5 testimony. “Regardless of our dedication and commitment to excellence during our time representing the NCAA, we will never reap the economic benefits of our labor.”

“A lot of student athletes are providing for their families, but they weren’t able to do that [before NIL] because they [couldn’t] use their brand or their Instagram or their different social media,” Ellsworth says. “So we really felt passionate about this because we wanted to give our student athletes a chance — and other student athletes a chance — to use their name and image and likeness to create other sources of income. I mean, we can’t really work other jobs because this is basically a full-time job.”

Whether college athletes will ever be compensated for actually playing sports is anybody’s guess. Forer sees group licensing deals coming before anything like salary or revenue sharing.

But it may not be as far out of reach as it seems. In concurring on the Alston ruling, Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote, “Nowhere else in America can businesses get away with agreeing not to pay their workers a fair market rate on the theory that their product is defined by not paying their workers a fair market rate.”

Perhaps predictably, Pac-12 commissioner George Kliavkoff — who stepped into his role in July — has said Kavanaugh’s opinion could be viewed as “an invitation to attack the very foundation of the collegiate model.”

As a counterpoint, Forer says NIL could benefit college football and basketball in that college students would be able to earn money while staying in college instead of facing the choice of going pro.

Former Ducks offensive lineman Max Forer, now a lawyer with Portland firm Miller Nash. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Former Ducks offensive lineman Max Forer, now a lawyer with Portland firm Miller Nash. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

And Jason Rittereiser, a managing partner at HKM Employment Attorneys , who practices in both Portland and Seattle, says while college athletes exist in a liminal space between pro sports and amateur sports, they drive revenue for their schools.

“Should these individuals be compensated for playing sports at the university level? It’s an open question. I think it’s a good question. I think the answer to that question should be yes,” he says. “I think from a public-policy standpoint, the answer should be yes. And from an employment perspective, from an employment-law perspective, it’s sort of hard to make the argument that they’re not employees of the university. So I think from that perspective, they ought to be compensated.”

Wagoner says the appeal of college sports is much bigger — and deeper — than the question of whether athletes get paid.

“You just turn on any American-rules football game on a Saturday afternoon in the fall, and you see 100,000 people wearing the same-colored T-shirt,” she says. “That’s power right there. What the rules are, and what’s legal and what’s not legal, and who’s getting paid and how much — those are offshoot questions to, ‘What is it that brings 100,000 people together every Saturday to wear the same-color shirt?’ That’s what college sports is. And I don’t think that’s going anywhere anytime soon.”

Editor’s note: This story has been corrected from an earlier version to accurately describe Ryan Ballis’ major and more precisely characterize the relationship between Penn National and Barstool Sports.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.