Banks have closed thousands of branches in the last two years, many in rural communities. Small-business owners say they’re being left in the lurch.

Four months after Liz Pharas opened the Nyssa Mercantile in 2019, she found out her bank branch was closing. At first she considered transferring her account from Umpqua Bank to U.S. Bank — the only other bank branch with a physical location in her town.

But that process was too complicated, she says.

“I was going to have to switch 20-some-odd autopays,” Pharas tells Oregon Business. “I said, ‘I’m stopping this process because it’s pointless.’”

Nyssa Mercantile owner Liz Pharas. Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

Nyssa Mercantile owner Liz Pharas. Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

Instead she drives to Ontario twice a week to make bank deposits and get change for the register. Ontario isn’t far — it’s about 13 miles away, but that’s a 20-minute drive or roughly an hourlong round-trip by car, when bank runs used to be a matter of running to the branch a couple of blocks away.

“For a while I was doing it every day, and that just was not working. So I had to come up with a scheme to do it twice a week. I kind of have no choice. I can’t just send an employee over,” Pharas says.

And even if Pharas had switched bank accounts, she’d still be leaving town to do her banking.

In November of last year, U.S. Bank announced that it would be closing its location in Nyssa, leaving the town without a physical bank location. That bank shut its doors for good in January, a little over a year after Umpqua shuttered its Nyssa location.

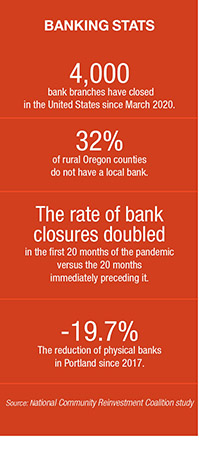

Nyssa is not alone: According to a study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, more than 4,000 bank branches have closed in the United States since March 2020. According to Rural Development Initiatives, 32% of rural counties do not have a local bank.

The trend didn’t start with the COVID-19 pandemic. The rise of direct deposits and online banking — including mobile-banking apps — have made trips to the bank obsolete, or at the very least rare, for many customers. Banks have responded by cutting teller jobs and closing locations throughout the country. At the same time, experts say, the banking industry was already trending toward consolidation.

The trend didn’t start with the COVID-19 pandemic. The rise of direct deposits and online banking — including mobile-banking apps — have made trips to the bank obsolete, or at the very least rare, for many customers. Banks have responded by cutting teller jobs and closing locations throughout the country. At the same time, experts say, the banking industry was already trending toward consolidation.

But the pandemic has accelerated those trends. According to NCRC’s research, the rate of bank closures doubled in the first 20 months of the pandemic versus the 20 months immediately preceding it.

The reduced availability of in-person banking services is not limited to rural areas; large cities also lost a large number of physical branch locations, NCRC notes. And Portland has actually lost more physical banks than any other major metropolitan area. In 2021 there were 421 bank branches in operation across the Portland area, a 19.7% reduction from 2017.

But the loss of a physical bank branch means different things in different places and for different people. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s biennial survey on Americans’ banking habits, in 2019 28.4% of Americans with bank accounts reported they had visited a bank branch 10 or more times in the past year — down from 35.4% in 2017. But households of older adults and households with volatile incomes were much more likely to make frequent bank visits, the survey notes.

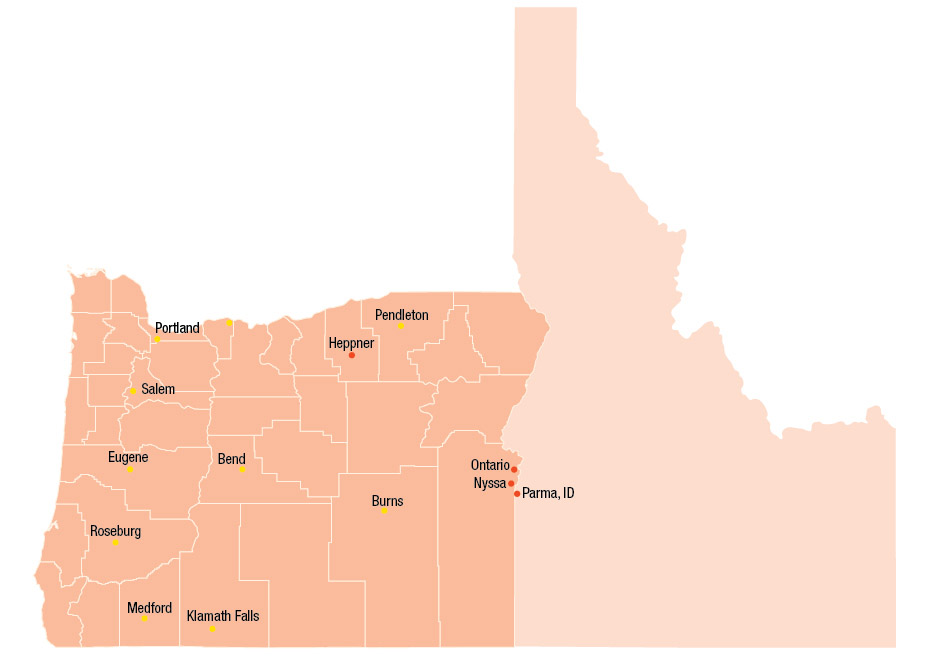

And, Nyssa city manager Jim Maret notes, small-business owners are heavily dependent on in-person banking services to make regular deposits and to get change. He makes daily trips to Parma — which is in Idaho, 8 miles away — to make deposits on behalf of the city.

“We used to just go down the street,” says Juan Munoz, who bought Stunz Lumber and reopened it as Munoz Building Center last August. “Now we’ve got to kind of schedule around it to go to Ontario.”

Juan Munoz, owner of Munoz Building Center. Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

Juan Munoz, owner of Munoz Building Center. Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

Pharas grew up in Paul, Idaho, a town of 1,169 people in Southern Idaho. Her father, Steve Haun, opened a hardware store in Paul when she was 2 years old, then relocated to Nyssa in 2001. That store shuttered in 2008.

In 2019, after several years teaching dance at her own studio in Nyssa and at Treasure Valley Community College in Ontario, Pharas decided to open a hardware store herself. It’s situated a few blocks away from her father’s former store, in a building that she says housed a hardware store 100 years ago. The store sells an array of standard hardware-store equipment alongside locally made soap and gardening supplies. Pharas’ parents are among her 10 employees.

They tell Oregon Business this isn’t the first time they’ve had to deal with banking changes.

“When we first moved here, the people [who ran the store before us] used Wells Fargo. We had to go to Parma [in Idaho, across the river] or Ontario,” Pharas’ mother, Robin Haun, says. The Nyssa-based branch they switched to operated under several different names before it became Umpqua Bank and then closed. (OB reached out to Umpqua Bank for comment on the 2019 closure but did not receive a response.)

“This is the trend that big banks are [following],” Maret says. “They don’t really care about the rural communities anymore and they’re leaving. It’s not going to help growth any.”

Banking Small

At first blush, the movement of financial institutions toward consolidation of services — and out of less-populated areas — looks like business as usual. The financial sector has trended toward consolidation for decades. And many service-oriented sectors have shifted to doing business online to the greatest degree possible, especially in the last two years.

But that’s not quite the whole story.

The last big push toward consolidation in banking was in 2007 and 2008, says Jason Richardson, senior research director at NCRC. That was driven in part by the impending financial crisis.

And at the same time banks were getting bigger, new ones were opening, says Linda Navarro, president and CEO of the Oregon Bankers Association.

“In the past, when we’ve seen consolidation, we’ve also seen new banks form,” Navarro says. “I think that further leads to consolidation in our industry, when you don’t have new banks organizing.”

She believes the last new bank formed in Oregon that is still operating is Lewis & Clark Bank, which opened in Oregon City in December 2006.

And Richardson notes that the 2008 financial crisis happened the year after the iPhone was introduced. The shift to mobile internet use would have an eventual rippling effect that saw banks cutting costs and looking to expand their digital offerings — not their physical presence in communities.

“Banks have shifted their strategy, right? They’re no longer looking for that geographic footprint,” Richardson says.

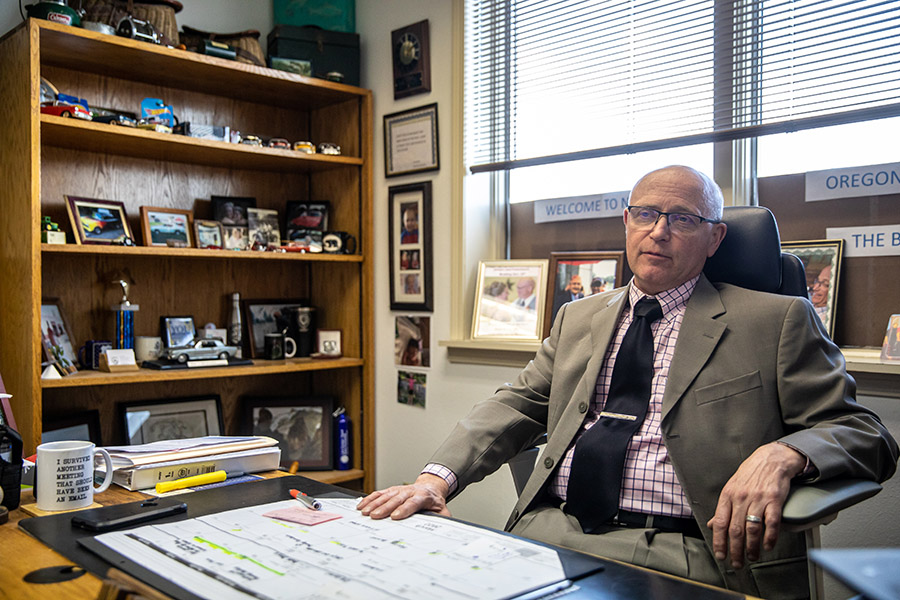

Jeff Bailey, president and CEO of the Bank of Eastern Oregon, which is based in Heppner and operates 20 branches and five loan-production offices in Oregon communities, says it’s true that banking has changed — and that works for plenty of customers.

Jeff Bailey, president and CEO of the Bank of Eastern Oregon, near the bank’s Heppner headquarters. Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

Jeff Bailey, president and CEO of the Bank of Eastern Oregon, near the bank’s Heppner headquarters. Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

“I’ve heard many people say, ‘I don’t need a bank branch anymore. Our customers’ bank branch is in their pockets.’ Maybe that’s true for some customers,” Bailey says, noting that his company offers mobile- and online-banking services.

“It’s not handy for the local grocery store to have to drive 30, 40, 60 miles to have to get a change order,” Bailey adds.

Bailey also tells OB that BEO is not looking to open any new branches at this time. And the reason is a bit surprising.

What banks have seen in the past two years is the reversal of what caused so many to fail after the stock-market crash of 1929, when panicked customers withdrew money from banks at such a rapid clip that there was nothing left to loan out. Or, for that matter, in the years between 2008 and 2013, when nearly 500 banks failed, according to the FDIC.

In 2020 banks reported an influx of $3.3 trillion in total deposits, including more than $1 trillion in deposits in the first two quarters, due to PPP loans to businesses as well as stimulus payments to individuals, who have been able to save more in the last two years than they had historically.

That flood in deposits and resulting spike in liquidity has accompanied a low demand for loans despite low interest rates. So there’s no incentive to expand.

“Typically with banks, the reason they gather deposits is so they can fund loans,” Bailey says. “Right now there’s so many deposits chasing fewer loans. That whole liquidity situation would have to change on the part of banks to the point where they would have to push to gain more deposits. It’s drastically different than anything we’ve ever seen previously.”

The next act

Maret says he’s been in contact with some financial institutions that have shown an interest in opening a branch in Nyssa, but that he has nothing firm to announce.

Nyssa experienced a slight dip in population between 2010 and 2020, according to U.S. Census data, which show the population was 3,197 at the most recent full census and 3,267 in 2010. The town — whose claim to fame is a preponderance of geodes in the area, celebrated every summer at the annual Thunderegg Days festival — has struggled economically since its largest employer, Amalgamated Sugar, downsized 150 jobs in 2005.

Nyssa’s city manager, Jim Maret. Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

Nyssa’s city manager, Jim Maret. Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

But Maret says the economy is beginning to grow. In recent years several new businesses have opened, including Nyssa Mercantile.

The city also recently approved a 52-unit park for recreational vehicles, Maret says. He also describes plans for a reload center in an area south of town that, stakeholders say, will accelerate shipping in the area. And Nyssa has approved about 18 new building permits in the past year, Maret says, most for new homes. That may not seem like much, but Maret says it follows a nearly 20-year lull in home construction.

“I think U.S. Bank — just my opinion — made a huge mistake. They didn’t really talk to anybody in Nyssa to find out what we have going on,” Maret says. “That’s what big banks look at — numbers, not people.”

Evan Lapiska, a spokesperson for U.S. Bank, notes that there is still a U.S. Bank ATM in Nyssa. He also noted that customers can still bank via phone and schedule virtual appointments with tellers, in addition to using online-banking services, including mobile deposits.

Maret is skeptical that older and low-income customers will make that switch.

“My mom’s in her 80s. Do you think my mom’s going to be very good at doing an app or banking on a computer?” Maret asks.

And it’s not just a matter of comfort with technology, Richardson says, but a matter of access. Lower-income customers are less likely to have access to the internet — and rural communities have lower bandwidth speeds in general than their urban counterparts.

Navarro says there are some technological workarounds that could make it easier for rural customers to access services without having to drive to a physical branch.

Linda Navarro, president and CEO of the Oregon Bankers Association. Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

Linda Navarro, president and CEO of the Oregon Bankers Association. Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

They include smart ATMs — kiosks that allow video chats with tellers — which could be easier to use than online-banking services used at home. But those are high-bandwidth services, and rural communities generally lack the broadband infrastructure necessary for such technologies to operate.

Another potential way to expand banking services — particularly to lower-income people who may not currently have a bank account — is postal banking, which allows customers to access some basic financial services, like savings accounts, through the local postal service. In March Congress passed a reform bill ending the requirement that the Postal Service prefund retirement benefits — and also lifting a 2006 ban that prevents USPS from offering non-postal services.

Another solution that might be particularly relevant for small businesses, Richardson says, is offering longer hours at branches — like Ontario or Parma — where customers may be driving from remote locations to access services.

“We’re working hard to embrace technology and be the bank of the future. We haven’t given up at all on the fact that having a local bank does increase service in the community,” Navarro says.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.