For a growing number of Oregonians, the end of the traditional office is in Bend.

In December 2019, Kasey Yanna and her husband sold their house in Texas and moved into a recreational vehicle — with their dogs, Motor and Tazor, and their son, Ethan, then just 1 year old.

Yanna had quit her job as an administrator at the Duncanville Independent School District outside Dallas. She wanted to shift to contract work; her husband had already committed to being a stay-at-home dad. They wanted to travel and explore the country as a family.

And they did — for a few months.

Kasey Yanna and family recently moved to Bend, where she rents a desk at The Haven, a coworking space. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Kasey Yanna and family recently moved to Bend, where she rents a desk at The Haven, a coworking space. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

The same month Yanna’s house sold, doctors in Wuhan, China, identified a cluster of cases of the respiratory virus that would eventually be identified as COVID-19. By March it had upended life around the world and, for a while, halted Yanna’s travel plans.

“We had to scramble and find an RV park that would let us in,” Yanna says, because so many were closing. They stayed at an RV park in California for two weeks, then drove to Oregon and stayed at Crater Lake RV Park in Prospect for two months.

In July 2020, the family visited Bend; in September, they came back to stay.

Before the pandemic hit, Yanna had never visited Oregon before and knew nothing about Bend.

“I had never heard of it. It didn’t look impressive on Google Maps,” she says.

But her family camped in the Deschutes National Forest, near a biking trail, and fell in love with the area. Yanna hadn’t ridden a bike since she was a child, but she and her husband bought bikes. They started going to an indoor bouldering gym. Yanna started visiting local coffee shops and writing blog posts about them, impressed that they all either seemed to roast their own beans or source their beans from local vendors.

“I liked the small-town feel and businesses supporting each other, and it wasn’t too big or too small,” Yanna says. “I’m from Austin, Texas, which is very large. My partner’s from a small town in East Texas — very small. So Bend was a great medium size for us.”

When Yanna left her job in Texas, she talked to her supervisor about shifting her role to one that could be done remotely. Now she does communication work for the district, and also provides content and consulting services for a number of other freelance clients, including the Haven, the Bend co-working space where Yanna rents a desk.

In 2019 Bend already led the nation in the share of residents who worked from home, according to U.S. Census data. That number was published as the city wrapped a decade of significant growth, with 99,178 residents calling Bend home in 2020 versus 76,629 in 2010, due in part to a tech-sector boom.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and suddenly a much larger share of the workforce was telecommuting.

State economist Josh Lehner noted in a December blog post that the number of remote workers in Bend did not grow by as great a degree in Bend as it did in other places with high remote-work populations — or in the United States generally. Bend’s share of remote workers grew by 7% in 2020 versus 2019; in the U.S. as a whole, that share grew from 5.7% to 15.8%. That’s a jump of more than 10%.

Bend’s rate of remote-work growth was less dramatic, but its numbers were higher to begin with, and remain higher than average with 12.1% of residents reporting they telecommuted in 2019 and 19% telecommuting in 2020, according to Census data.

Lehner also noted that, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, the overall number of Americans working from home has dropped from its peak during the early months of the pandemic: 35% of the workforce worked remotely in May 2020, compared to 11% in November 2021.

While those figures come from a different data set than the Census figures, they do suggest that remote work is here to stay — and that Bend’s status as a “Zoom town” is likely to outlast the pandemic.

Where Bend may not have specifically worked to attract tech workers, or remote workers generally, other places are making a more concerted effort.

Matt Sayre is the managing director of Onward Eugene, a 501(c)(3) dedicated to “inclusive prosperity.” That includes grants that allow companies to provide on-the-job training for new hires who may be a near-perfect fit for a job but lack one specific skill and need assistance getting up to speed. It also includes a partnership with the Oregon Bioscience Association to monitor and advance the bioscience sector in Lane County.

And it includes a startup accelerator called 942 Olive Street, which opened in 2016 and has closed its physical location due to the pandemic, but plans to reopen in 2022.

Sayre’s organization has also been holding events to welcome new businesses to the area — and also to allow remote workers to meet and connect.

“We had a lot of [remote worker] talent come here in the last year,” Sayre says. “I think we are an attractive place. We’ve got some pretty tremendous quality of life.”

Sayre describes Eugene as “a big town becoming a small city,” one in the process of shaking off its reputation as a flyover town. (Southwest Airlines, for example, began flying out of Eugene in spring 2021.) Its location near the mountains and coast and its relative proximity to Portland give it an edge for telecommuters looking for amenities and a lower cost of living than can be found in, say, the San Francisco Bay Area.

“We really feel like we’re in the middle of everything,” Sayre says.

Sayre’s organization has also run a coworking space it plans to reopen in 2022.

The concept of coworking spaces — offices that rent small desks to solo, remote workers or to companies, sometimes on a short-term basis — took some time getting traction.

Jon Stark, interim CEO of Economic Development for Central Oregon, says his organization tried to start a coworking space in Deschutes County about 10 years ago but didn’t manage to get it going.

But BendTECH, a nonprofit coworking space on the west side of Bend, did open around that time — in 2011 — and has been joined by several others.

BendTech, a nonprofit coworking space in Bend. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

BendTech, a nonprofit coworking space in Bend. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

They act not only as offices, allowing remote workers a quiet place to work and clear work-life boundaries, but as social and networking hubs, offering happy hours.

Yanna says she’s made almost all of her friends in Bend through the Haven, but has also found work blogging on behalf of the space and has done some content-creation work for another tenant at the space, where she meets people both in the Haven’s café and at bimonthly happy hours.

Tiffany White, executive director of the Haven, says the space includes 13 private offices, with two organizations renting two offices each and 20 dedicated desks. The space’s individual clients include a mix of remote workers and entrepreneurs.

The Haven’s executive director, Tiffany White. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

The Haven’s executive director, Tiffany White. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

“I think the most common thread that really connected with our members is that people were just looking for community again, they were looking for connection, they were looking for energy, they were looking for creating their new work team, right with the people around them,” White says. “It was so much about being able to feel the connection to people that we were really missing during the pandemic.”

Stark argues that recent data on work-from-home growth don’t tell the whole story of what’s happening in Bend.

Stark tells Oregon Business that a friend of his who works in real estate delivered keys to 12 homeowners in Bend in November.

“Not one of those homes were delivered to somebody who lived here prior,” Stark says. “At one brokerage, every new home delivery was to an out-of-the-area migrant.”

Jon Stark, interim CEO of economic development for Central Oregon. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Jon Stark, interim CEO of economic development for Central Oregon. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Stark says he’s not aware of anything specific local leaders have done to attract remote workers.

“I think we’ve been caught in a perfect storm related to the pandemic,” Stark says. “We had the assets necessary to be successful as a remote-work town, or Zoom town, with the lifestyle and livability here, and as technology advanced, the world grew up around us. Technology helped accelerate that opportunity.”

Remote work became more and more prevalent before the pandemic, and Bend was already a place where people had a desire to live.

That’s borne out by data: Stark says in 2010 his organization surveyed managers of 17 companies who moved operations to Central Oregon. Of the 17, 16 had been visitors to the area first.

And it’s borne out by anecdote, too. Just as Yanna and her husband traveled to the area on a whim and fell in love with it, Stark tells OB he decided to move to Bend in 1999 while driving home from a ski trip.

“My girlfriend, who became my wife later, said, ‘Hey, you want to move here?’” he says. As he recalls, his response was, “Absolutely.” They lived in Seattle at the time, but wanted to drive 40 minutes to go skiing and not deal with a lot of traffic on the drive.

Brian Lindensmith, community manager at BendTECH, notes that revenue there has stayed mostly flat during the pandemic — “the pandemic didn’t help us, but it didn’t hurt us, either” — but he is seeing an uptick in member inquiries, especially from people looking to move to the area.

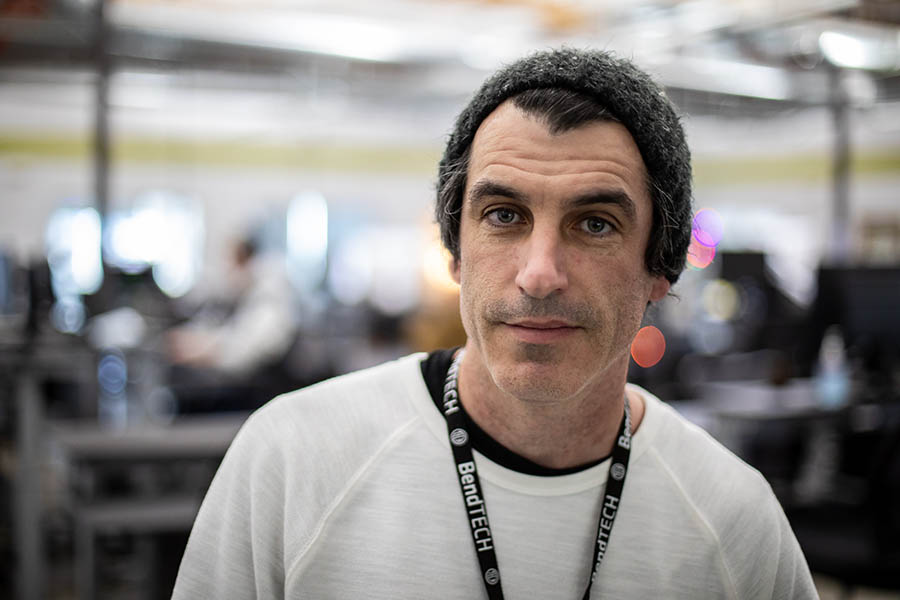

Brian Lindensmith, community manager at BendTECH. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Brian Lindensmith, community manager at BendTECH. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

“Every week I get a message from people who just moved up from the Bay Area, or Portland or something, to Bend, who want a remote space to work.”

Lehner notes that the overall impact of in-migrants who work remotely can be good for communities.

“Outside of the Portland area, those working from home tend to be concentrated in occupations that aren’t as prevalent locally as they are nationally,” he wrote in July 2020. “In essence these workers are voting with their feet, saying they want to live in our communities.”

And instead of waiting to find a job in their chosen field, he notes, they make it work by either bringing a job with them or starting their own business.

“This increase in economic diversification should make our regional economies more resilient and better able to withstand different types of recessions over time,” Lehner writes.

Stark tells OB that when he moved to Bend, he didn’t have a job lined up, but he was determined to find something and make it work. But, he notes, the cost of living in the area was lower at the time.

Now it’s easier to bring one’s job to a new town, but the spiraling cost of housing in municipalities across the country also means it’s more necessary. Or at least, moving to a town like Bend on a whim without a job lined up — as Stark did — is far more difficult than it used to be.

Stark describes a close friend of his who moved to Bend from the Bay Area and telecommutes for a California company, who just bought a house in Bend in 2021 after renting for some time.

“He said, ‘You know, I’m going to finally sell that house in the Bay Area.’”

With the profit from that sale, Stark’s friend was able to buy not one new house in Bend but two. He’s renting out the second to build equity.

“The affordability here versus the Bay Area is still a big delta,” Stark notes, even though housing prices in Bend have increased sharply: Realtor.com notes that the median house listing price there was $755,000 in December 2021 versus $479,000 in January 2019.

Bend has made a concentrated effort to add more supply to the market, Stark says, but demand continues to outstrip supply.

And longtime residents are feeling the pinch, but not every new resident is like Stark’s friend.

“We can’t afford to buy a house here and have the lifestyle we want. So we really had to analyze our priorities,” Yanna says. Her income as an independent contractor is lower than it was when she worked a regular, W2 job; her husband, who previously worked as an electrician, wants to continue to be a stay-at-home dad.

So Yanna’s family is staying in the RV for now. And affordability is not the only factor: While they love Bend and may want to have a home base there sometime in the future, they aren’t dead-set on staying in the area.

“Even if Bend is our home base, we’d like to spend a month traveling, seeing places that we haven’t seen yet, and come back and then travel again for a month,” Yanna says. “That was our goal. We haven’t made that happen yet. But I think eventually we would love to have a house here.”

And for now, the combination of being her own boss and living in Bend means Yanna can take a few hours off every Tuesday and Thursday and go to the climbing gym, or check out paddleboards the Haven makes available to members.

“I had to unlearn a lot of things when I decided to leave my nine-to-five job and work for myself,” Yanna says. “I had to unlearn some mindset about work and about productivity, and then teach myself: How do I want to work? What do I want my workday to look like? You know, it doesn’t have to be nine to five every day.”

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.