BY VIVIAN MCINERNY

Travis Knight wants to release a movie a year. Can he pull it off?

Travis Knight wants to release a movie a year. Can he pull it off?

BY VIVIAN MCINERNY | PHOTOS BY ADAM WICKHAM

Cobblestone streets show the wear of centuries. Weeds poke through the cracks. Lopsided buildings lean into each other, exhausted by their battle against time and gravity. It could be a well-preserved European village, except all this fits on a tabletop in Hillsboro. The Laika film studio, a former warehouse, is sectioned off with portable black walls and drapes to form a maze of stop-motion animation stages. In peak production, it’s abuzz with a staff of about 430 of Oregon’s creative class.

“It’s an odd group of people,” says Travis Knight with a wry smile, and it’s clear he is happy to count himself among the tribe. He takes a seat at a folding table near a lit set, shielding his eyes from the glare. Then he slides his chair back out of the spotlight.

Literally and figuratively, Knight is in and out of the spotlight. As CEO, president and lead animator at Laika, he is at once head honcho and foot soldier, executive and artist, suit and creative. He’s the man with an eye on the big picture and one of the guys fussing over the small stuff — nay the minuscule stuff — of moving a tiny puppet’s tinier hand.

That duality is reflected in Laika’s approach to business and filmmaking. Far from the hit factory of Hollywood, the studio is handcrafting animated films using a stop-motion technique almost as old as the industry itself. But Laika is also using the latest technology, 3-D printers and hand-drawn and computer-generated images for an inventive mashup earning it praise in 2013 as among the world’s top 10 most innovative companies in the entertainment industry, according to Fast Company magazine. The studio’s first two films were nominated for Oscars in the best animated feature category. Their third, The Boxtrolls, opened in late September.

In an industry of behemoth conglomerate studios churning out blockbuster movies to satisfy investors on the one hand, and independent artists scrambling for financial backing on the other, Laika is uniquely positioned. Backed by Phil Knight, co-founder of Nike and father of Travis, the studio can afford to take risks on creative endeavors and still be a major contributor to Oregon’s $120 million-a-year film industry. Now Knight, and Laika, are raising the stakes.

In an industry of behemoth conglomerate studios churning out blockbuster movies to satisfy investors on the one hand, and independent artists scrambling for financial backing on the other, Laika is uniquely positioned. Backed by Phil Knight, co-founder of Nike and father of Travis, the studio can afford to take risks on creative endeavors and still be a major contributor to Oregon’s $120 million-a-year film industry. Now Knight, and Laika, are raising the stakes.

The studio plans to amp up production to release one film a year, says Knight. “No stop-motion animation studio has ever been able to do that,” he says. Laika, he adds, “wants to be the bravest animation studio in the world.”

Wearing a tight-fitting, short-sleeve shirt, with close-cropped dark hair, Knight, 40, has the physique and determined intensity of a personal trainer. He’s known for putting in the longest hours on set. It would be easy to dismiss him as a wealthy man with a healthy ego indulging in a quirky passion.

But Laika is more than a vanity project for a son of a big gun. Coraline had a $60 million budget and grossed $124 million, according to the Internet Movie DataBase (IMDB.) A similar budget for ParaNorman, 2012, grossed $107 million worldwide. (By comparison, the Fantastic Mr. Fox stop-motion movie, voiced by George Clooney and Meryl Streep, was made for $40 million and grossed $46 million). Laika has hired star talent for its movies — Sir Ben Kingsley voices a snooty character in Boxtrolls — but the studio’s reputation in the industry as a peculiarly Oregon outsider remains intact.

But Laika is more than a vanity project for a son of a big gun. Coraline had a $60 million budget and grossed $124 million, according to the Internet Movie DataBase (IMDB.) A similar budget for ParaNorman, 2012, grossed $107 million worldwide. (By comparison, the Fantastic Mr. Fox stop-motion movie, voiced by George Clooney and Meryl Streep, was made for $40 million and grossed $46 million). Laika has hired star talent for its movies — Sir Ben Kingsley voices a snooty character in Boxtrolls — but the studio’s reputation in the industry as a peculiarly Oregon outsider remains intact.

“Visiting Travis and Laika … always gives a glimpse of an alternative reality to the usual Hollywood corporate machine,” says James Schamus via email. A screenwriter and producer with credits on Dallas Buyers Club and Brokeback Mountain, and CEO of Focus Features until its merging with FilmDistrict, Schamus partnered with Laika on Coraline and ParaNorman.

“Travis works as an artist and craftsman among artists and craftspeople; the vision and leadership of Laika comes from this deep communal connection to the creativity of hundreds of co-workers,” Schamus says. “Make no mistake, Travis is a leader, but his leadership has created a space of collegial creativity. Everyone takes risks and shares them with each other. Even the simplest tasks are artistic ones.”

“Travis works as an artist and craftsman among artists and craftspeople; the vision and leadership of Laika comes from this deep communal connection to the creativity of hundreds of co-workers,” Schamus says. “Make no mistake, Travis is a leader, but his leadership has created a space of collegial creativity. Everyone takes risks and shares them with each other. Even the simplest tasks are artistic ones.”

Balancing business and art can be a struggle, Knight says of his intentionally varied roles. “It asks different things of you. But I think that, in an odd way, each role I have within the company makes me better at the other.”

“The danger with any artist is you can get kind of swallowed up in the details,” he says. On the flip side, the all-business man “can potentially lose sight of what it’s all about: creating these beautiful works of art, these films.”

In an age of computer-generated images, stop motion seems to make about as much sense as using a horse-drawn cart to deliver email. It’s a labor-intensive style of animation in which an object is physically manipulated in tiny increments between frames of film to create the illusion of movement. The technique is nearly as old as the movie industry itself and doesn’t attract the big audiences of CGI films. The top-grossing stop-motion Chicken Run, from Aardman Animations of England, produced in partnership with DreamWorks, took in $224 million. That’s a pittance compared to the $1.275 billion of Disney’s CGI Frozen. Granted, almost nothing comes close to Frozen, but more than 60 animated films grossed in excess of the top stop-motion entry.

Some studios might conclude that the paying public doesn’t give a green Gumby if a film is lovingly hand-crafted. Surely, a CGI movie would be a safer bet after what The New York Times called the worst summer box office take since 1997. But Laika isn’t playing it safe.

“We’re building our brand. We’re seeding it out into the world,” Knight says. “This is what Laika is; this is what it means. You only get that by releasing a film every year.”

Such ambition sounds courageous. Or some kind of hubris. Either way, Knight’s career trajectory looks like a rocket launch: straight upward from animation intern in 1998 to president and CEO of his own studio in 2005. Of course, it’s unlikely anyone could do that without the big money and business guidance of Phil. Knight senior invested in the now defunct Vinton Studios, where Travis learned the art of stop-motion animation. Some say the elder Knight simply bought and rebranded the studio for his kid, but Will Vinton’s 2003 lawsuit accusing the Knights and other board members of unfairly ousting him was dismissed in court. Questions about the evolution from Vinton Studios to Laika make the otherwise straight-talking Knight turn the slightest bit prickly.

Such ambition sounds courageous. Or some kind of hubris. Either way, Knight’s career trajectory looks like a rocket launch: straight upward from animation intern in 1998 to president and CEO of his own studio in 2005. Of course, it’s unlikely anyone could do that without the big money and business guidance of Phil. Knight senior invested in the now defunct Vinton Studios, where Travis learned the art of stop-motion animation. Some say the elder Knight simply bought and rebranded the studio for his kid, but Will Vinton’s 2003 lawsuit accusing the Knights and other board members of unfairly ousting him was dismissed in court. Questions about the evolution from Vinton Studios to Laika make the otherwise straight-talking Knight turn the slightest bit prickly.

“There’s a misperception,” he says of the relationship of the two companies. “Vinton was insolvent when we looked and thought there was something worth salvaging.”

Any possible last ties to Vinton Studios were severed in July 2014 when Laika’s in-house commercial division spun off to form an independent and unrelated company. The split made sense. Knight says Laika’s key leadership team struggled to divide its time between making feature films and commercials. Clients included M&M, Kellogg’s and ESPN. While commercial work can provide steady income, movie making has more potential to make the big bucks, even in today’s risky box office climate. Domestic box office take is the biggest, but not the only part of the equation. Revenue from other avenues including foreign markets, television rights, DVD sales, rental and online streaming from services such as Netflix, Hulu and Amazon can continue to trickle in years after a movie premiere.

“The investment is all front loaded,” Knight says. “We are still seeing money coming in from Coraline and ParaNorman.” He declines to divulge Laika revenues or the budget for The Boxtrolls except to say the money spent creating all three Laika films wouldn’t equal the price tag of a single animated feature from Pixar or DreamWorks.

Not that Laika is short on funds. “Every studio has a bank they draw on,” says Tom McFadden, executive director of the Oregon Media Production Association, a trade organization. “This [access to Knight’s fortune] just puts them in a league with the major players.”

And that’s where Oregon Film wants the industry. The branch formally named the Oregon Governor’s Office of Film & Television has been working on it since 1968, but it’s been only in recent years with more generous financial incentives that things have come into sharper focus. And it seems to be paying off. The state’s film industry has increased twentyfold in 10 years, says McFadden. The $120 million annually added to the Oregon economy that can be directly credited to film and television production is only part of the picture. This helps feed an indigenous commercial business of about $300 million a year, he says, noting dozens of creative shops that produce animated advertising, digital content and video games.

Television series and films shot in the state, while on the increase, remain relatively transitory business. Having Laika studio as a permanent resident is another thing entirely. McFadden says he can’t emphasize enough what that kind of infrastructure means to the state’s burgeoning film industry. “Economic impact is the reason to care for Laika,” he says.

In Oregon’s almost starstruck enthusiasm to entice movie makers, little mention is made of the fact that a hire-layoff model is the industry standard; the nature of movie making is that crews are hired and laid off as production ebbs and flows. Nevertheless, if Laika has a smash hit with The Boxtrolls, movie audiences won’t be the only ones applauding. “If any one company does well, any related business does well,” says Ray Di Carlo, a producer, director and co-founder of Bent Image Lab in Portland, responsible for the terminally hip rats on Portlandia, the Hallmark Channel special Jingle All the Way, and countless animated commercials. “It’s like restaurants; when you get three to five restaurants on a street, then it’s a destination.”

In Oregon’s almost starstruck enthusiasm to entice movie makers, little mention is made of the fact that a hire-layoff model is the industry standard; the nature of movie making is that crews are hired and laid off as production ebbs and flows. Nevertheless, if Laika has a smash hit with The Boxtrolls, movie audiences won’t be the only ones applauding. “If any one company does well, any related business does well,” says Ray Di Carlo, a producer, director and co-founder of Bent Image Lab in Portland, responsible for the terminally hip rats on Portlandia, the Hallmark Channel special Jingle All the Way, and countless animated commercials. “It’s like restaurants; when you get three to five restaurants on a street, then it’s a destination.”

Gretchen Miller, an executive producer at Hive-FX in Portland, echoes the sentiments. Her company produces special effects including the terrifying transformations of Grimm characters into monsters, and clever clips such as a smack-talking whale for a Power Ball commercial.

“Anything to elevate the perception of animation, visual effects, etc., in Portland is a plus,” she says via email. “Especially if it would encourage local and out-of- state advertising agencies and businesses to hire Oregon-based production companies for high-end projects. Right now, a lot of commercial projects are taken to L.A.”

One local director grumbled, off the record, that Laika tends to fire locals and hire outsiders. Laika does have employees from Britain, Bulgaria, France, New Zealand and elsewhere, though most are from the U.S., says Suzanne Johnson, head of human resources. Laika employees fluctuate between 320 and 430 with an average of 390, Johnson estimates, with about 97% working longer than six months. For every 25 stop-motion and computer-generated animators, Johnson figures, Laika has 100 support people, including everyone from puppet makers, costumers, and rigging to accounting and finance. The studio works with colleges nationwide including Pacific Northwest College of Art, Oregon College of Art and Craft and the Art Institute, and is “in touch with Portland State University” and community colleges, says Johnson, “to make sure we are looking in our backyard first.”

One local director grumbled, off the record, that Laika tends to fire locals and hire outsiders. Laika does have employees from Britain, Bulgaria, France, New Zealand and elsewhere, though most are from the U.S., says Suzanne Johnson, head of human resources. Laika employees fluctuate between 320 and 430 with an average of 390, Johnson estimates, with about 97% working longer than six months. For every 25 stop-motion and computer-generated animators, Johnson figures, Laika has 100 support people, including everyone from puppet makers, costumers, and rigging to accounting and finance. The studio works with colleges nationwide including Pacific Northwest College of Art, Oregon College of Art and Craft and the Art Institute, and is “in touch with Portland State University” and community colleges, says Johnson, “to make sure we are looking in our backyard first.”

As Laika moves toward its goal of one film a year, production schedules will overlap and the result, Johnson says, “will likely be a growth of crew.” To accomodate that growth, the studio is shopping for bigger digs, The Oregonian reported in July.

Will Laika’s ambitions compromise its creative integrity? Knight says no. “That can happen as you attempt to do more stuff. Stuff can get watered down,” he says. “It’s been critical that we balance that.”

Schamus, the Hollywood screenwriter and producer, thinks they’ve got it down.“The trick of Laika is that there is a seamless connection between its huge ambitions — artistic and commercial — and its respect for detail and the patient work of making things by hand,” he says. “Maybe it’s a Portland thing, but it certainly isn’t the norm where I come from!”

Laika’s yin and yang is a reflection of Oregon, Knight says. “There is a spirit here of innovation, of individuality, of idiosyncratic distinctiveness,” he says. “You have a place where you have a lot of dissidents. You have a bunch of tree-hugging hippies and a bunch of clodhopping hillbillies kind of commingling with each other.” Any time you have that kind of tension, he says, “interesting things come out of it.”

That tension exists in the very style of animation that is Laika’s specialty. On the one hand, the studio uses the basic move-an-object-shoot-a-frame, stop-motion technique pioneered in the 1897 movie The Humpty Dumpty Circus. On the other, they’re breaking new ground using digital tools to erase the metal supports needed to hold a character upright, for example, and the latest 3-D color printers to produce the hundreds of tiny masks a puppet might require to simulate changing facial expressions.

“We are pushing the medium beyond where it’s ever been,” says Knight, sounding less boastful than factual.

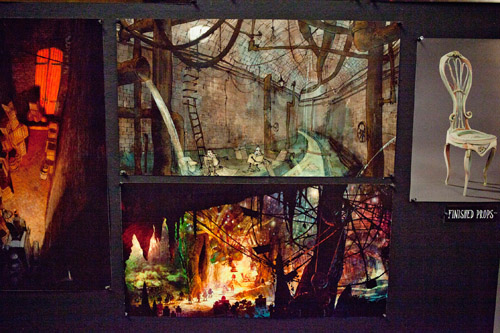

The finished results have a surreal appearance — what Knight calls “recorded dreaming” — of the old-school stop-motion movies that so captured his imagination as a kid. To achieve that look, Laika brings a remarkable level of detail to the making of its puppets. Every wig, twig, dress and piece of furniture is handcrafted. The fabric for a costume might be handwoven to get the right texture, silk-screened for scale or hand embroidered with hair-thin metallic threads. Before final filming, each scene is blocked out and shot first in a quicker, jerkier sequence to see how things will play out.

All that meticulous craftsmanship and hours of work pales compared to that of the animators. A single frame of film can take a half-hour to create, and a good day’s work might yield two seconds of useable film. The result is that many viewers mistakenly think Laika films are entirely computer generated.

It makes one wonder: If Laika could make computer generated films that had the same look as stop motion animation, would the studio still bother with the labor intensive process? Knight says it’s not possible. The movie would look different. The light would be wrong. It would feel different. For an imaginative guy, he suddenly seems stuck on replay. But say it was possible. What then?

It makes one wonder: If Laika could make computer generated films that had the same look as stop motion animation, would the studio still bother with the labor intensive process? Knight says it’s not possible. The movie would look different. The light would be wrong. It would feel different. For an imaginative guy, he suddenly seems stuck on replay. But say it was possible. What then?

“I do think the process of creating art is inextricable from the art itself,” says Knight after a pause. “Stop-motion is completely unique in animation in that it is a kind of performance art. You start at one place and end at another, and it kind of warps time.”

Maybe it is those time-warped moments when the dissonance finds harmony, business becomes art, and the clodhopping hillbilly gives a tree hugger a big old bear hug.

Whether Laika manages to do what no other stop motion animation studio has before and releases a film a year remains to be seen. But for both the Hillsboro studio and the broader Oregon film industry, cautiously producing a picture here and there may be riskier than spending more to speed up production. Like stop motion animation itself, only when all those separate, small, still shots are cranked up to full speed and the time between stop and motion disappears does a smooth continuous big picture appear.

Click to view a photo slideshow:

{artsexylightbox singleImage=”/images/stories/articles/archive/oct2014/Laika-blogLaika_AW40_500px.jpg” path=”/images/stories/articles/archive/oct2014/Laika_slideshow/”}{/artsexylightbox}