It’s smart business to have a stake in Oregon’s $166 million college football industry.

It’s smart business to have a stake in Oregon’s $166 million college football industry.

STORY BY BEN JACKLET

COLLEGE SPORTS IN OREGON |

|

Budgets, all schools and all sports statewide2003…………………………………………$99 million 2004……………………………………….$111 million 2005……………………………………….$124 million 2006……………………………………….$141 million 2007……………………………………….$155 million 2008……………………………………….$166 million A 68% increase from 2003 to 2008 SOURCE: U.S. Dept. of Education |

|

PHOTOS BY LEAH NASH |

This fall’s incoming class at Pacific University is like no other in the institution’s 161-year history.

For one thing, the average freshman male is larger than usual — much larger. That’s because more than 100 of the 500 incoming freshmen at this stately campus in Forest Grove are football players.

After five years of planning and fund-raising, Pacific is resuming a football program that the university dropped in 1992. The mighty Boxers return to the field this month for their 100th year of competition, and it needs to be said that the 99th year was not a stellar one. During its last season before dropping football, Pacific lost all nine of its games and one of its players tragically died after receiving a concussion from a head-on collision during one of the games.

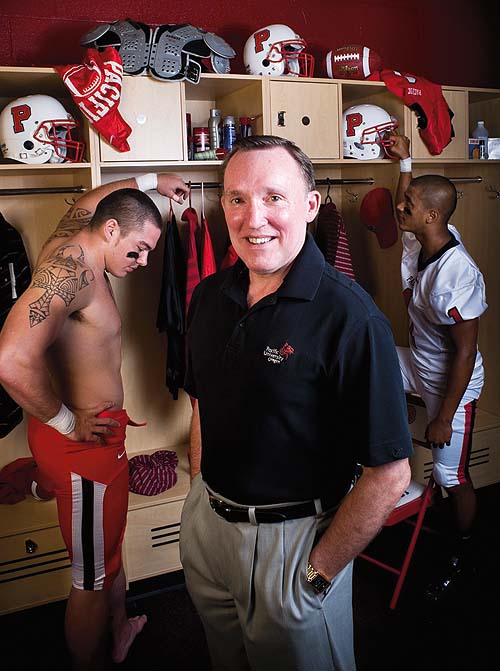

But Pacific’s ebullient director of athletics, Ken Schumann, couldn’t be more thrilled to bring back football, and his enthusiasm extends beyond the usual pep rally banter. Bringing back football was a business decision, he explains. As a private liberal arts college with 1,500 undergraduates, a $50 million endowment and a fairly hefty tuition of $31,000, Pacific has been struggling to boost enrollment during hard economic times.

Recruiting young men to campus has become particularly challenging. Last year the ratio of females to males was 69 to 31. The quickest way to even out that ratio, and to bounce back from the recession, Schumann explains, is to bring back football.

Unlike big-school powerhouses, Pacific does not pay athletic scholarships. But it offers the opportunity to earn playing time as a freshman, to be a part of something new and exciting. That’s a strong pitch to make to graduating high school athletes, and it has worked. Schumann had hoped to bring in 50 players for the debut season and Pacific ended up gaining over 120, between freshmen and transfers. Not only does that number of players equal teams at far larger football schools, it also represents a significant boost for Pacific’s bottom line. “For every student that we bring in, after you take all the costs, the net revenue generated for the university is a little over $17,000,” says Schumann.

Multiply 120 players by $17,000 each and you get more than $2 million.

With a 2,000-seat football arena, $50 season tickets and a $2.5 million athletic budget, Pacific will never be mistaken for the multi-million-dollar programs at the University of Oregon and Oregon State University. But it does have something in common with the Ducks and the Beavers and many other institutions of higher education: Its athletic program is growing like crazy, and the growth is driven by football.

Between 2003 and 2008, sports programs at Oregon universities increased their budgets by 68%, their football revenues by 51%, and game-day expenses by 111%. It’s part of a national trend of contention for many within academia, but there appears to be no reversing it, in Oregon or elsewhere.

The market forces at work are strong, even during an economic downturn. Taken as a whole, college sports in Oregon can be viewed as a $166 million entertainment industry — and that’s just if you add up the program budgets, never mind the hotels, restaurants, gas stations, book stores and bars that benefit from game-day consumer spending, the businesses that produce the television and radio ads promoting big games, the media outlets that benefit from the hype, the workers who build a seemingly endless supply of stadiums ranging from the $11 million Lincoln Park Athletic Complex in Forest Grove to the $200 million Matthew Knight Arena in Eugene. Then there’s the sponsorship/branding machinery of Beaverton-based Nike, the most powerful force in sports marketing on the planet.

The sports programs at the heart of this industry range from plucky Linfield College, the Division III football and baseball powerhouse that wrote the playbook on boosting enrollment through sports, to the University of Oregon, which has grown from a budget of $14 million in 1996 to $70 million today.

|

Pacific University’s director of athletics, Ken Schumann, says bringing back football after 18 years has already boosted the Forest Grove school’s bottom line. More than 120 newly recruited athletes will play for the Boxers this year. Pacific completed its football locker room and installed a goal post on its field just a month prior to the season opener. // PHOTO BY LEAH NASH |

For better or worse, many athletic departments operate as aggressive growth businesses. But unlike tech companies that measure growth by revenues and income earned, athletic departments measure growth by budget, or amount spent. And the amount spent in this industry tends to grow faster than the amount made. Earned revenues from ticket sales, television contracts, corporate sponsorships, advertising and licensing rarely keep pace with expenditures from coach’s salaries, scholarships, travel, recruiting, equipment and supplies, insurance, marketing, maintenance and debt service for construction projects. So departments buttress earned revenue with voluntary or hidden student fees, tax-exempt philanthropy in the form of booster club donations and subsidies from the university and/or the state.

The biggest exception to all of this bleeding of red ink can be football, which generates about two-thirds of the revenues of college sports along with a hard-to-measure blast of marketing hype that boosts everything from beer sales to ticket scalping (which is legal in Oregon) to university admissions.

Still, even with revenues from football, if these sports programs were real businesses, many of them would have been forced into bankruptcy by a steep drop-off in sponsorships and donations during the recession. Practically every program operates at a loss, with the exception of Oregon’s largest and most complex amateur sports business, the Oregon Ducks.

The Ducks have received more than $200 million in donations from Nike founder Phil Knight. As a result, UO is one of just 20 or so Division I schools running “self-supporting” sports programs, operating without subsidies from the state or the university. In 2008 the university’s athletic department earned $17.4 million from ticket sales, $10.6 million from the governing body of the NCAA and the PAC 10 Conference, and $2.7 million for TV, radio and Internet rights. But the largest revenue category for sports was donations, which totaled $18.3 million of the department’s $60 million budget that year.

On the expense side, UO athletics spent $7.6 million on coaches, $6.9 million on athletic scholarships, $4.5 million on travel, $3.7 million on game days, $2.9 million on fund-raising and marketing and $1.1 million on recruiting. All of those expenses continued to grow during the recession.

In addition, the Ducks have taken on millions of dollars in new debt to pay for their basketball stadium, for which they will have to pay $15 million this season and $18 million per year starting in 2011-2012.

In spite of the escalating costs, the UO sports program breaks even, due to the largesse of Knight and other donors and strong ticket sales, especially in football. UO’s track program is legendary and its basketball team is on the cusp of becoming a national contender. But most importantly from a business perspective, the football team has sold out 68 consecutive home games and last year made it to the Rose Bowl.

For all that success, the Ducks have been hounded by embarrassing antics by players on and off the turf and questionable deals by administrators. Following a season-opening loss to Boise State a year ago, star running back LeGarrette Blount punched an opponent in the face on national TV. Star quarterback Jeremiah Masoli damaged the Duck brand further by pleading guilty to burglary and pot possession. Punctuating those debacles was the $3.2 million golden parachute paid to departing athletic director Mike Bellotti.

In recruiting a replacement for Bellotti, university president Richard Lariviere made it abundantly clear that the institution would follow standard academic procedures. “The AD search was a straight-up process with a very carefully composed committee representing students, athletics, faculty, coaches and administrators,” he says. “It was a textbook search.”

Ultimately Lariviere chose Rob Mullens, a straight-laced, soft-spoken man from West Virginia who worked in accounting for Ernst & Young prior to joining, in order, the universities of Miami, Maryland and Kentucky, where he served as associate director of a $79 million program that grew by 70% over his eight-year tenure.

“Rob had experience with a high-visibility athletics program that is the object of intense scrutiny,” says Lariviere. “He also had great business credentials, which is very important for the athletics program at this stage of its evolution.”

A Eugene Register-Guard editorial called Mullens “an inspired hire” for “an athletic department that for too long operated with disturbing independence from the school’s administration and an absence of public accountability.”

At the press conference announcing the hire, Mullens told reporters, “Sound fiscal integrity is a very important component of college athletics and I’ve been very fortunate to work for a self-supporting program.”

As for the donors who enable UO to be “self-supporting,” Mullens said he had not spoken with Phil Knight prior to getting the job. He spoke with Knight by phone for the first time the morning the announcement went out that he had been hired. So much for the misconception that boosters had co-opted control of the department.

Asked about expectations regarding Knight and Nike, Mullens said emphatically and then later repeated, “Nike is the strongest brand in sports.”

It’s certainly the most ubiquitous brand in sports. If the critics are correct and the industry of college athletics is an out-of-control arms race, then Nike is the biggest defense contractor of all. But some critics are giving up in frustration after concluding there is no stopping the college sports money train. UO English professor James W. Earl campaigned energetically against the overblown hype of college athletics throughout the 1990s and early 2000s but he says he “gave up that Quixotic campaign several years ago… when the new UO arena was approved, which is to say, when sanity flew out the window.”

UO’s new $200 million basketball stadium, scheduled to open in early 2011, will be the most expensive college basketball arena in the nation by the time it is completed. The Oregonian has reported that the new academic center for athletes will cost an additional $41.7 million.

“With the new arena coming online and additional expenses of hiring personnel, we’ve got a couple of tight years coming up,” says Lariviere. “I don’t think we’ll be in any financial trouble but we’re going to have to manage our pennies carefully. But we should probably manage our pennies carefully in any year.”

|

|

The University of Oregon Ducks have expanded their athletics department by a factor of five over 15 years and has sold out 68 straight football games. // PHOTOS COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF OREGON |

Another huge driver in the college sports industry is television money.

The annual Civil War rivalry between the Oregon Ducks and the Oregon State Beavers routinely sells out months in advance, but last year’s game may have been the biggest year ever on the national stage. Scheduled on a Thursday night rather than a weekend, the game had ESPN all to itself, with the winner bound for the Rose Bowl. It ended up being one of the network’s most watched games of the season and that single game reportedly added about $350,000 each to the Duck and Beaver athletics departments.

The Beavers came up short in that particular contest, but not for lack of effort, both on the field and on the money side. Even without a super-booster on the level of Phil Knight, OSU athletic director Bob De Carolis has nearly tripled his budget over his 12 years on the job, from $18 million to $50 million.

“The engine that drives the growth is football,” says De Carolis. “Football, and building the base there, going from paid attendance of 15,000 to …averaging about 42,000 tickets sold. And the growth of fundraising… In ’98 we were raising about $1.5 million. By ’04 it was $5 million. Then we hit an all-time high a few years ago at $11.4 million.” De Carolis estimates that about 70% of the revenues his department makes come from football. As he sees it, “football and to a lesser extent basketball finance the rest of the athletics department.”

Still, for all that growth, the Beavers are deep in the red. A 2009 NCAA report estimated that the Beavers ran a deficit of $3.8 million during the 2007-2008 season when factoring in subsidies from state lottery games and student fees.

According to ESPN’s college sports database, Oregon State earns about $8.5 million in annual ticket sales — a sizable sum but just half of what UO earns at the gate.

The department’s bottom line could soon be improving, however. The PAC 10 is expanding and is looking for a new television contract, which is divided among the teams in the conference based on TV appearances. The current contract pays the conference $58 million, while a future contract could pay twice that or more.

Besides, even if the Beavers lose money as a program, De Carolis believes the athletics program pays off from a marketing perspective, especially when you factor in the popularity of college sports on TV.

“It really is a good investment as a PR machine,” he says, “to help schools get their brands out there.”

Meyer Freeman, COO of the Oregon Sports Authority, agrees from a broader statewide perspective. “The impact of a Civil War game getting ESPN all to itself is huge in terms of great exposure for Oregon,” he says. “It generates an overall awareness of Oregon being a great place to live in, work in and visit, and that has benefits over the long term. It’s almost impossible to quantify what it’s worth, but it’s definitely valuable anytime you put your state on a platform that widely viewed.”

Lariviere says the money UO made by reaching the Rose Bowl “pales in comparison to having your logo in 15 million homes for four hours.”

|

|

The Oregon State University Beavers have tripled their sports budget over a dozen years under director of athletics Bob De Carolis. // PHOTOS COURTESY OF OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY |

Sports fans may not be aware of this fact, but the mascot for the largest public university in Oregon is not a Duck or a Beaver. It is a Viking. Portland State University has 27,000 students. About 280 of them are athletes.

Portland State’s athletic director, Torre Chisholm, has been on the job for three years, and he acknowledges that PSU has to overcome the perception of running an underperforming sports program. “Portland State’s a great university and we need to represent that by being a great athletic department,” says Chisholm. “Athletics can be the most visible personification of excellence. Right or wrong, it’s athletics that ends up getting the most media coverage and recognition in the university setting.”

Chisholm has hired nine new head coaches over his three years on the job, partially because his $10 million department is not wealthy enough to keep pace with the market rate for top coaches. He points out with pride that four of the young coaches he’s hired won conference championships in their first year. Unfortunately, these sports weren’t football, so they didn’t generate much in the way of headlines — or revenue.

The Vikings had their glory days under quarterback Neil Lomax in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but they have struggled in recent years, playing to more empty seats than filled ones. The university hired former pro coach Jerry Glanville to resuscitate the program in 2007, but Glanville resigned last November after losing 24 games and winning just nine.

“The hard thing about ticket revenue is it’s so tied to performance,” says Chisholm. “Bottom line is, we have to make some progress in football and we have to sell some tickets.”

The marketing hype that surrounds big-time college sports obscures the fact that for every football team selling out stadiums and boosting admissions there is another playing to lackluster crowds and losing money. The most common approach to solving that problem is to invest as much as possible in the team (recruiting a former pro coach, for example) to make the program stronger.

But the University of Portland proves that a university can run a big-time athletics program without playing football. Athletic director Larry Williams oversees a $12 million, 60-employee department that has grown dramatically due largely to the phenomenal long-term record of its men’s and women’s soccer teams.

“Nobody does soccer better than us, and arguably that’s because we can focus on it,” says Williams. “We’re not focusing on that big animal that is football.” But UP is very much the exception rather than the rule.

Approximately 10% of the University of Portland’s 3,000 or so students are athletes. That’s a high percentage for a school that offers scholarships, but it’s nothing compared to Division III schools that use athletics as a recruiting tool.

In Forest Grove, more than one-third of Pacific’s undergraduates are athletes. Over his six-year tenure as AD, Ken Schumann has doubled the number of student athletes at Pacific and more than doubled the number of full-time coaches. He expects the growth to accelerate now that football has returned.

So far the revived football program at Pacific has been exceeding Schumann’s expectations. The Boxers had planned to play eight games but recently added a ninth due to all the excitement. “We will sell out every game this year,” Schumann predicts. “We’re going to take our lumps in the beginning because we do have a lot of freshmen. But I think we’ll surprise some people on the field.”

On the business side, Pacific already has surprised some people, and other institutions are taking notice. George Fox University, a similarly sized Christian school in Newberg, plans to restart its football program in 2013.

George Fox fielded a football team from 1894 to 1968 but dropped it when the team could no longer compete. Bringing back football after a 42-year absence is a point of pride to University President Robin Baker, and a smart business decision. Like Pacific, George Fox has fairly steep tuition ($36,000 including room and board) and women make up 62% of students. By restarting football, “we’ll draw around 75 new students who are men who will pay to be a part of George Fox University and to play football here,” says Baker. “It makes perfect financial sense.”

George Fox already has started building a $6.5 million sports complex with lacrosse and soccer fields as well as a 1,200-seat football stadium. The university will hire a coaching staff to rebuild the team from scratch and is looking forward to its largest incoming freshmen class ever in the fall of 2013 — if not by number of students then certainly by weight.