Not many company histories include a Grateful Dead show, but in Eugene, the town that birthed Ken Kesey and the Oregon Country Fair, such distinctions matter.

Hippie-era natural foods manufacturers face tough decisions as their businesses grow and pressure builds.

STORY BY LUCY BURNINGHAM // PHOTOS BY LEAH NASH

| ||||||||

Chuck and Sue Kesey have owned and operated Springfield Creamery, producer of Nancy’s Yogurt and other popular brands, for 50 years. | ||||||||

|

Not many company histories include a Grateful Dead show, but in Eugene, the town that birthed Ken Kesey and the Oregon Country Fair, such distinctions matter. On a hot August day in 1972, 20,000 Deadheads attended a one-time concert to raise money for Springfield Creamery, which desperately needed an infusion of cash to continue making Nancy’s Yogurt.

For the creamery, the story represents not just a do-or-die entrepreneurial moment but a taste of the cultural origins that helped shape business during the past 50 years. The creamery has always been owned and operated by Sue and Chuck Kesey (brother of the late novelist Ken), and these days the Kesey’s children manage plant operations and market the brand. The couple hopes a crop of grandchildren will one day join the Creamery to continue in the spirit of fierce independence.

“We have no one to answer to but ourselves,” Sue Kesey says. “We do what we believe in because ultimately we are responsible for what the consumer gets, how our employees are treated and how the product evolves.”

In Eugene and Lane County, Springfield Creamery has become part of a nationally notable cluster of natural foods manufacturers similar to those in the San Francisco Bay area and Boulder, Colo. The ethos of eating in Eugene, a liberal and environmental hotbed, helped spawn Toby’s Family Foods, Golden Temple, Springfield Creamery, Coconut Bliss, Emerald Valley Kitchen, GloryBee Foods, Oregon Ice Cream, Turtle Mountain Foods and Rising Moon, companies that sprang from a distaste for all things corporate and non-organic. Many of them started in home kitchens, between anti-Vietnam War protests and food co-op meetings.

A ticket from 1972 harkens back to an epic concert by the Grateful Dead to save Springfield Creamery. |

Since then, the natural foods movement has grown in prominence, especially among consumers nationwide. Nutrition Business Journal reports a 5.5% growth in sales of organic foods and beverages in 2009 for a total of $24.4 billion. That figure does not include “natural” foods, a broad term that describes foods that are minimally processed and free of artificial additives.

Many of Eugene’s natural foods companies have grown exponentially, pushing owners and founders into new, uncomfortable territory. Instead of inviting the Grateful Dead to town and printing tickets on the back of yogurt labels, owners and presidents now field calls from corporate lawyers and venture capital firms.

Caren Wilcox, former executive director of the Organic Trade Association, says the growth in the organic and natural foods business sector has created a new paradigm. “Increasingly smaller companies are looking for exit strategies,” she says. “The founders who built the business are in their 60s or 70s and need to make decisions about how to pass on their businesses while maintaining their value proposition. This often means they have to get their investment out of the business while hoping to see their company continue to exist.” Some of the largest American food companies — Kellogg’s, Hershey’s and Heinz — were once founded by individuals. From her perspective, organic company founders often feel more personally invested in their companies than their counterparts in other industries.

“Organic growers have struggled,” Wilcox says. “They have had to go against the mainstream to produce products and bring them out, which is bound to bring a certain intensity to what they’ve built and what they’ve done. It’s a very emotional thing for these people to sell their companies.”

|

In the early 1980s, Mel Bankoff started a small organic salsa and bean dip company in Eugene called Emerald Valley Kitchen. In 2002, he sold the company to Monterey Gourmet Foods for $5.5 million. “I realized if you’re going to take a successful smaller business national, you have to gear up every aspect of the business and that requires greater risk,” Bankoff says. “After 20 years, the business was no longer fun and exciting.”

Monterey Foods continued to produce Emerald Valley products in Eugene with Bankoff heading the organics division. After three years he resigned from the job and now says the company treated him as “an obstructionist.” In September 2009, Monterey Foods closed the Eugene plant and moved operations to Kent, Wash., putting 25 employees out of work.

Bankoff says he expected the move, just one in a series of disappointments that began immediately following the sale. “If I had the ability, I never would have sold to Monterey Foods,” he says. “They turned it into the very company I spent so many years of my life trying to avoid by creating a model that was all about the triple bottom line. For me, making money was just one aspect of success. Success was a byproduct of the value and intention behind trying to be in service to the community and have the business support itself.”

Selling to another company doesn’t always produce a negative outcome, says Wilcox. She cites Stonyfield Farm, the world’s largest producer of organic yogurts. Based in New Hampshire since the 1980s, the company sold a majority share to Groupe Danone, a French food and drink company. “They’ve been able to maintain their quality while getting capital from Danone and becoming a valued part of Danone’s investments,” she says.

In Lane County, the departure of Emerald Valley and Rising Moon Organics, which sold for an undisclosed amount to Blue Marble Brands in Connecticut, may represent a losing battle for a county with 10.9% unemployment. Even so, the state or county has yet to accurately quantify the impact of these natural foods manufacturers. According to Workforce Oregon, in 2008 about 12% of Lane County’s manufacturing jobs were classified as “food processing,” just 1,526 people. But unlike most industries, food processing jobs increased between 2007 and 2009.

|

|

|

Spices and apples await processing at Toby’s Family Foods in Springfield. |

The relatively small number of people in food processing may not accurately represent the scale of the industry, says Michael McKenzie-Bahr, Lane County community and economic development coordinator. He says the City of Eugene, Lane County, the Eugene Water and Electric Board, and the University of Oregon’s Community Planning Workshop are currently creating a survey, which will lead to an accurate market assessment of the county’s food industries. In 2003, 15 of the county’s natural food companies responded to a similar survey, reporting 334 local employees and annual local payrolls of at least $8.39 million, with annual sales between $76,000 and $16 million.

Any current survey may quickly become outdated. Privately owned Golden Temple, a cereal and tea maker that was founded in Eugene in the 1970s, recently sold to Hearthside Food Solutions, a Michigan company, for $65.2 million. The sale affects the cereal portion of the business, with 230 employees in Eugene. Before the sale, Golden Temple ranked as one of the county’s largest natural foods companies, with over $100 million in annual sales.

At Sundance Natural Foods, a tiny single-location natural foods store that’s been in business since 1971 in Eugene, customers carefully navigate narrow aisles packed with all manners of health food, from teff flour to locally picked morels.

Last year, the staff taped typed paragraphs on the bulk bins that read, “Dear Sundance customer, we regret to inform you that we will no longer carry bulk granolas from Golden Temple.” The signs went on to explain that Golden Temple had substituted commercially grown oats for organic oats, which did not meet the store’s product standards. Also, the staff knew Golden Temple had moved some of its production facilities from Eugene to California.

Like many in Eugene, the store’s owner, Gavin McComas, has a long history in the local natural foods world, starting in 1970 when he worked at Springfield Creamery. “Our customers are very sensitive to the quality of foods they eat,” McComas says. “We do have strong product standards. We are the gatekeepers.”

The awareness of food sourcing and quality reveals the kinds of pressure placed on natural food manufacturers by the local community. “I’m sure there were judgments,” Mel Bankoff says about the sale of Emerald Valley. “Eugene is a very critical and judgmental community by its nature.” (Sundance still carries Emerald Valley products.)

|

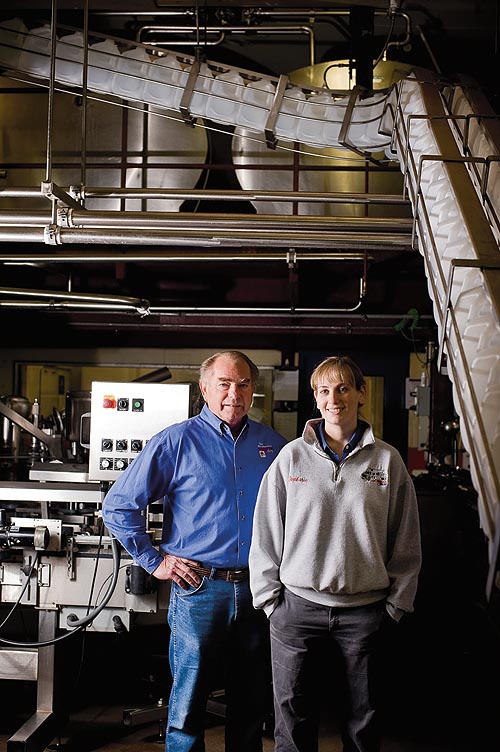

Jonah Alves, president of Toby’s Family Foods, and his mother, Toby, who started the company in her kitchen more than 30 years ago. |

At one point, Bankoff was a member of the Willamette Valley Sustainable Food Alliance, a trade association of 52 natural foods businesses in Lane County. For business owners, the Alliance offers a forum for discussing everything from ingredient sourcing and the employee pool to labeling laws — one distinct perk of operating a business in a natural foods hub. President Felicia Colden says the members of the group support each other unconditionally. “Most of us are here because we’re trying to sustain each other and make sure we all do stay in business the way we want to stay in business,” she says. “But if people decide that [selling to a large corporation] is the way to go, we support that as well.”

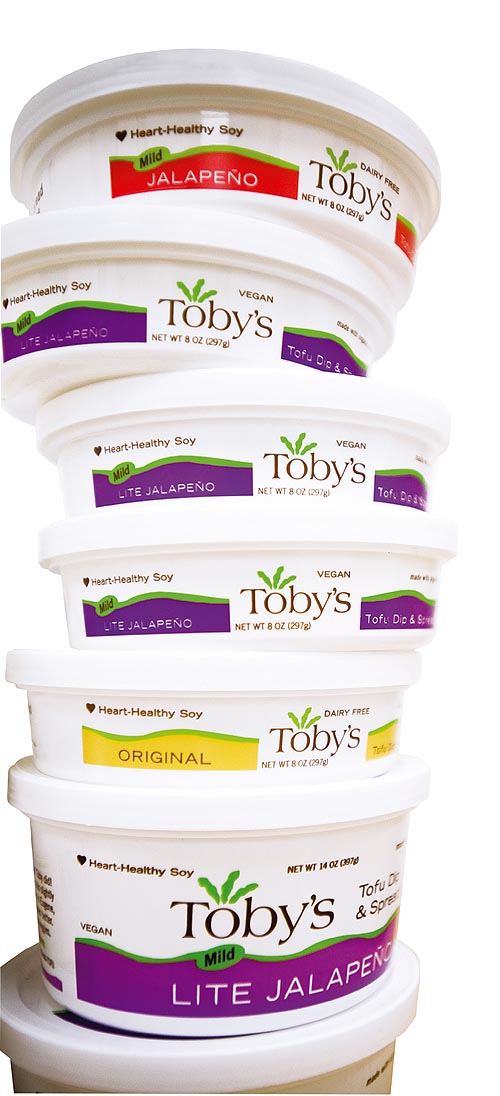

Selling a company doesn’t mean all or nothing. Toby’s Family Foods, which produces tofu dips and spreads the company once called “patés,” began during the 1970s when Toby Alves cooked up the recipes in her Eugene kitchen. In 2005, Toby’s sold shares in the company to local investors, and today Alves’ son, Jonah, serves as the company’s president.

Sheldon Rubin, one of the company’s owners, says raising capital allowed Toby’s to purchase a new piece of high-pressure processing equipment, which extends the shelf life of its products without using heat. The move allowed Toby’s to increase distribution throughout the I-5 corridor market, a region from the San Francisco bay area to the Canadian border that Rubin says contains 25% of the nation’s natural and organic food stores (and just 8% of the population). “Would we ever sell out?” Rubin says. “We’re not thinking about that right now. Never say never, but we’re focused on doing the best we can to increase sales in the I-5 corridor.”

In addition, the new equipment allowed Toby’s, which employs 20 people and keeps its sales numbers confidential, to acquire Genesis Juice and start producing organic, non-heat-pasteurized juices under that label, diversification that could help the company survive any slump in soy sales.

|

Lochmead Dairy owner Jock Gibson and his daughter Stephanie, general manager of the bottling plant, bought Coconut Bliss last year. |

Jock Gibson, one of the owners of family-owned Lochmead Dairy in Junction City, knows all about diversification. The gravely voiced elder of three brothers, who grew up on the family dairy farm down the road, opened the Lochmead milk bottling plant in 1965. Even though Gibson and his family made a name for themselves with cows and their milk, the plant also processes large amounts of nondairy milks (organic coconut milk from Thailand, to be exact).

In 2009, Lochmead bought Coconut Bliss from Larry Kaplowitz and Luna Marcus. During the span of a presidential term, the couple founded and nurtured the frozen nondairy dessert company from a trailer in their driveway to $4 million in annual sales — a condensed version of the classic Eugene natural foods company evolution. Lochmead had already been freezing and packaging the product for Coconut Bliss for two years. “When Luna and Larry got to a point where they couldn’t keep up, we didn’t want to let Coconut Bliss get away from us,” Gibson says.

Lochmead learned its lesson the hard way when it lost long-time client Turtle Mountain, another local non-dairy dessert company. Lochmead had diversified, with 43 Dari Mart convenience stores, a line of ice creams, milks, juices and other frozen dessert clients. But it could not keep pace with fast-growing Turtle Mountain, which built its own facilities in Springfield to keep up with growth. That was a setback. Coconut Bliss means opportunity.

Gibson downplays the irony of a dairy producing nondairy desserts. “There are no big surprises in what we’ve done,” he says. “The growth is as much as anything to take care of my growing family.” Besides, he says, the dairy has already been part of the natural foods movement by not using the artificial growth hormone rBST on its cattle, only sourcing milk from the nearby family farm and growing 80% of the dairy’s feed.

Coconut Bliss founder Larry Kaplowitz says these factors, and the fact that the company is a fourth-generation owned and operated business (Gibson’s daughter, Stephanie, is the plant’s general manager and son Scott runs the farm, among others), helped him bypass the “conventional choice” of selling Coconut Bliss to a corporation or a venture capital firm.

|

He says he doesn’t believe in the “trickle up theory,” the idea that a small values-based company will reshape the priorities of the acquiring company. “Our biggest fear was that the company would go in a direction we would feel regretful about and we would lose the culture, spirit and values we created it with,” Kaplowitz says. “That’s why we decided to go with Lochmead, where their overriding priority is to make sure the fourth and fifth generations have a livelihood.”

The Kesey clan believes the only way to provide for future generations is to keep Springfield Creamery in the family. After 50 years in business, the company remains family owned, employs 58 people and reports $21 million in gross sales in 2009.

Next to the processing room, where machines squirt yogurt into plastic tubs, the company’s offices look like a time capsule for the American cultural revolution, with Grateful Dead posters and photos of Eugene before the word Nike represented anything other than a Greek goddess. One day last summer, Chuck Kesey wore a poofy newsboy hat and grinned maniacally while shaking a vial of a strain of probiotics, or live bacteria, from Russia. “We’re extending the lives of our customers,” he says.

Kesey became interested in the health benefits of live bacteria, especially L. acidophilus, while studying dairy technology at Oregon State University, where he met his wife Sue. In 1960, the couple started a milk bottling business, and in 1969 a friend and company bookkeeper, Nancy Hamren, started making yogurt from the milk. Chuck Kesey added the live cultures and the brand was born.

Nancy’s Yogurt has attracted attention from outsiders. “Third parties have been interested in investing in or purchasing the company,” says Sheryl Kesey Thompson, vice president of marketing and daughter of Sue and Chuck. “I guess it must be a form a flattery, in that people see a strong brand and a viable business with longevity, but we have no interest in taking on investors or selling the business.”

Caren Wilcox predicts a different future of family-owned companies taking calculated risks, such as going public or finding trustworthy venture capital firms, which can allow founders to remain involved. “The food community has a long history of family-owned companies successfully expanding into national and international markets,” she says. “I don’t see any reason why some organic food companies cannot remain family-owned and remain regional or become national and international for many years to come.”

The Keseys remain in the category of businesses that plan to grow without outside funding, which requires patience not always exhibited in the business world. “We don’t take huge giant steps,” Sue Kesey says. “We’re slow and cautious about what we do.”