Locals reacted with shock and glee when Facebook revealed in January that it would be building its first data center in humble Prineville. But the story did not stay so gleeful. Electricity generation is the leading source of carbon emissions in the U.S., and data centers are notorious power hogs.

Locals reacted with shock and glee when Facebook revealed in January that it would be building its first data center in humble Prineville. But the story did not stay so gleeful. Electricity generation is the leading source of carbon emissions in the U.S., and data centers are notorious power hogs.

The pressure is on for Intel, Amazon, Facebook and Google to make their power-guzzling data centers green.

BY ADRIANNE JEFFRIES

| ||||||||

|

Locals reacted with shock and glee when Facebook revealed in January that it would be building its first data center in humble Prineville. A data center is not inherently exciting — it’s a warehouse stuffed with computers — but the arrival of a cool, fast-growing Internet company to this former mill town was an unexpected coup, and the timing could not have been better: Crook County struggled with an unemployment rate of 20% during the worst of the recession. WELCOME FACEBOOK quickly appeared on marquees at local businesses.

“This is certainly a first for Prineville. This is one of the largest economic development projects in the history of Central Oregon,” says Jason Carr, a manager at Economic Development for Central Oregon, a nonprofit that worked on the deal.

Carr says Facebook has already brought business to local restaurants, hotels, hardware stores and contractors. He now gets calls from companies who heard about the Facebook project in the Wall Street Journal and suddenly want to know more about Prineville. The “Prineville Data Center” page on Facebook has about 4,000 fans, dozens of whom posted thank-you notes, hearty welcomes and job inquiries in the comments section. One commenter from Bend wrote, “Honestly, as a Central Oregonian, how can anyone think this is anything but wonderful?”

More than 400,000 people disagree. That’s how many have joined a Facebook campaign opposing the data center, part of a full green guilt assault launched by Greenpeace less than a month after Facebook broke ground.

The offense?

Coal.

The digital age is supposed to be a greener era. Instead of driving to work, we telecommute. Instead of killing trees, we send emails appended with “please don’t print this.” But despite the analogy, the Internet is not a cloud. Every bit of data lives on a hard drive somewhere that is always on. Electricity generation is the leading source of carbon emissions in the U.S., and data centers are notorious power hogs; Facebook estimates its new data center will consume between 30 and 40 megawatts of electricity, says Carr, enough to power all the homes in Prineville more than twice over. That would make it one of the largest power users in Oregon.

A data center’s environmental impact is more than just energy use. These digital age factories can use up to 360,000 gallons of water a day for cooling. Copper wiring can exceed 60 miles. Data centers produce potentially toxic e-waste, which Oregon law does not require them to recycle (although most companies say they do). But energy use is the biggest issue for environmentalists. It’s also a big issue for huge technology companies that would rather be renowned for amazing breakthroughs than for burning coal and sucking rivers dry.

Click through for page two!

Want to make a comment? Go to the final page to comment.

Facebook is the fourth tech company to site a large proprietary data center in Oregon. Google launched a data center the size of two football fields in The Dalles in 2006. Amazon started building a comparably huge data center in Boardman in 2008, but it’s on hold due to the recession. And Intel, which makes chips for the servers that fill data centers, has a large data center in Hillsboro.

Google and Intel’s data centers, and Amazon’s planned data center, guzzle electricity as well, but they rely more heavily on carbon-free hydropower. The Google data center in The Dalles is estimated to use 103 megawatts an hour at peak, equivalent to the needs of more than 73,000 homes.

Hydropower has its own costs, but Greenpeace singled out Facebook because the utility that serves Prineville, Pacific Power, gets 58% of its energy from coal, a major contributor to climate change.

But coal is often the most affordable option for a data center that needs power 24 hours a day. Hydropower has become more costly now that the Bonneville Power Administration, which markets power from the Columbia River, has closed the loophole that let data centers get it on the cheap. The customer-owned utilities along the Columbia that receive federally subsidized power pass on their discounts to Google and other companies, but under new rules recently negotiated by BPA, the data centers of the future will have to buy their power at market rates.

And there will be more data centers. Thanks to the growth of the Internet and the popularity of cloud computing, these facilities are popping up all over the nation. That new visibility is subjecting them to public scrutiny for the first time. The Environmental Protection Agency adopted a standard metric for data center efficiency in April and will roll out Energy Star labels for data centers this month that would require third-party verification.

The EPA’s voluntary standards imply the possibility of mandatory standards, which coupled with the possibility of carbon pricing add up to strong incentives to improve efficiency. Regulation could mean serious costs for owners of power-hungry data centers. Giants such as Google have massive carbon footprints from gobbling electricity. Exactly how massive is unknown, but Intel, for example, has 100,000 servers worldwide. It’s estimated that Google has more than 1 million.

|

DATA CENTERS: BY THE NUMBERS

Cost of Facebook’s new data center in Prineville: $188.2 M Sources: EPA, Intel, Facebook, Fortis Construction |

Picture a very large, sleek-looking building that is very wide open inside. Inside there will be row, after row, after row of servers all stacked up to a man’s height,” says Ken Patchett, manager of the Facebook data center and former manager of the Google data center in The Dalles. “It’s kind of like a factory. Not like a tire manufacturing factory, but a factory nonetheless.”

He’s describing Facebook’s new Prineville data center, and so far, it sounds like your average server farm. Data centers usually have generators, cooling towers or chillers, possibly a power substation and miles of wiring under the floor. These climate-controlled warehouses hold racks of servers that take care of all the data and software on the Internet. They store e-books, Facebook profiles and websites, and perform all the work for search engines such as Google and services such as TurboTax.

But none of the other large data center owners will say how many servers they have or exactly how much power or water they use or plan to use. “We don’t comment about the power consumption on any of our facilities,” a spokesman for Google said woodenly, before laughing and adding, “Sorry!” Amazon responded to an official interview request by email within 60 seconds with a “No thank you.”

One reason for the secrecy may be that the answers would alarm us. But the commonly stated reason, protecting trade secrets, is probably also true. Companies see arsenals of servers as a competitive advantage. But designing a new generation of efficient data centers would be an even greater advantage. The trend even has its own buzzword: “data center greening,” and even though Greenpeace is not impressed, that’s what Facebook is doing in Prineville.

Much of the electricity used in data centers goes toward cooling. Without cooling, a room of servers will go from 70 degrees to 120 degrees in two minutes. Facebook’s data center, which is designed to achieve LEED Gold certification, won’t use the energy-sucking chillers that circulate water to cool servers in a standard data center. Instead, Facebook plans to use outside air to keep things cool. This “free cooling” system works best in arid climates, part of what tipped the scales in favor of Prineville. Patchett estimates it will cut energy use by 20% to 30%.

Click through for page three!

Want to make a comment? Go to the final page to comment

“Facebook, despite its tiff with Greenpeace, has made great strides. The entire move to Oregon is about having the ability to operate their overall infrastructure more efficiently,” says Rich Miller, editor of the trade website Data Center Knowledge. Facebook’s projected Power Usage Effectiveness, the EPA-adopted efficiency standard, is projected to be 1.15 — the best in the industry.

That record may not last long. “The data center industry has been working intensely over the past three years on improving energy efficiency of these facilities,” says Miller. “It’s been a broad-based effort and has required some change of thinking in the industry, partly because these companies never shared much information.”

But companies have recently started opening up about their data centers, and that openness has already spurred progress.

The free cooling principle that’s creating most of Facebook’s energy savings was first demonstrated on a large scale in 2008 by another Oregon data center owner: Intel, the nation’s largest purchaser of green power. In addition to its own facility, Intel makes chips for almost all data centers worldwide, says Don Atwood, head of a division called Data Center Forward Engineering and Strategy. The data centers in Oregon owned by Facebook, Amazon, and Google? “Intel would be in all of them,” he says.

Intel has goals for chip efficiency in each generation of processors, just like its famous goals for greater computing power, and last year it had a major breakthrough. Servers use almost as much energy when idle as when operating at capacity, but Intel designed a chip that can shut down parts of the server and power it back up automatically as needed. Intel also plans to publish a study this year showing that servers can run hotter than was believed, which would save energy used for cooling.

But the company making the most progress with data center efficiency is probably Google, which stands to lose the most from carbon pricing or regulation. “Google dwarfs everybody when it comes to energy use,” says Casey Harrell, an organizer with Greenpeace’s Cool IT campaign. “They’re trying very hard. They’re doing more on clean energy advocacy, trying to ramp down the cost of renewables. They’re saying, ‘We have a carbon problem. We can’t grow without increasing emissions.’”

Google is still tight-lipped about its data centers, but it has started talking more openly with the rest of the industry. Google hosted a summit last year on data center efficiency where it revealed, among other innovations, what one engineer called its “Manhattan Project.” Most data center owners build a redundant power supply to guard against outages. Google saves money and energy by equipping each server with a 12-volt battery instead.

“We believe we’re operating probably the most efficient data centers in the world,” says Joe Kava, director of data center operations at Google’s headquarters in the Bay Area. Kava says the company is constantly improving efficiency and although he wouldn’t talk in detail, he mentioned an experiment with a “proprietary chemistry” in The Dalles that will recycle water more efficiently. Google hopes to use 80% recycled water in all its data centers by the end of 2010.

There is an element of idealism in Google’s sustainability effort in addition to its obvious self-interest. Google.org, its nonprofit arm, is striving to make renewable energy cheaper than coal “in years, not decades” by investing in renewable energy projects, lobbying government and using Google products to “unlock information that enables innovation and raises awareness about the benefits of renewable energy.”

Reducing energy use in data centers is an imperative, but replacing coal would be a revolution.

|

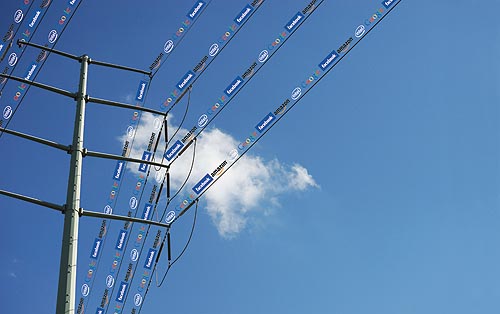

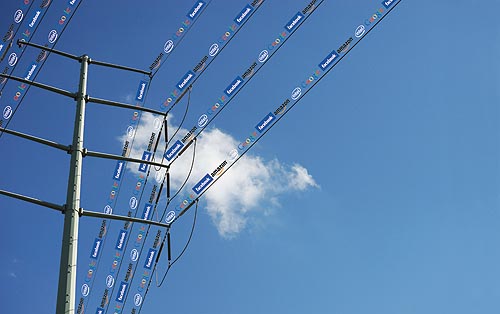

Local officials celebrated the unexpected arrival of Facebook in Prineville in January. The criticism from Greenpeace came a short time later.PHOTO COURTESY OF GOVERNOR’S OFFICE |

More than a third of large private data center owners in North America plan to expand this year, and many are expanding because they need more power, according to a survey by Digital Realty Trust, which builds and rents data centers.

It’s not just tech companies and Internet users who drive demand for data centers. Any business with lots of data could eventually need one. Accountants, financial firms, governments and universities are all major data center owners and renters.

“Eventually we’re going to see most of our stuff reside in the cloud and that’s going to drive demand for more and more data centers,” says David Aaroe, co-founder of Fortis Construction, the Portland-based firm that is building Facebook’s data center with DPR Construction. He estimates it will take between 10 and 15 years of building data centers before demand flattens out. Oregon will get more big data centers, he says, especially if a price is put on carbon. Fortis is currently evaluating Oregon sites for two clients.

A wave of data centers in Oregon would be a welcome flow of job-creating investments. Municipalities and economic development agencies are quick to offer incentives to powerhouse tech firms with money to spend, with good reason. But while the economic benefits are self-evident, the environmental costs are harder to predict.

Luckily, the companies with this green liability in Oregon are some of the most innovative players in one of the most innovative industries. Tech companies have improved efficiency across sectors, including retail, media consumption and travel, and now they’re doing it again: Efficiency gains in data centers will cut the carbon footprint of any business that relies on data. Giving farsighted, flexible companies such as Google, Intel, Amazon and Facebook the responsibility of bringing sustainability to the Internet is like assigning everybody’s homework to the smartest kid in the class. And because of economic pressure, growing public awareness, the specter of regulation and, yes, a sense of social responsibility, they’re working hard to get it in on time.