Film festivals across the state struggle to stay on the red carpet.

Film festivals across the state struggle to stay on the red carpet.

Film festivals across the state struggle to stay on the red carpet.

Film festivals across the state struggle to stay on the red carpet.

By Jennifer Netherby

In 2004, Katie Merritt, then in her mid-30s, left her job as a California realtor and moved to Bend, where she decided her dream job would be running a film festival.

Bend was growing, the economy was strong and she figured newcomers like her would welcome it. “It seemed that the people moving to the area were coming from areas that had fairly rich cultural offerings,” she says.

When Merritt, whose only connection to film was as an attendee of Sundance, South By Southwest and other festivals, approached her first potential sponsor, real estate developer Brooks Resources, the company thought it was such a good idea they donated more than Merritt had requested.

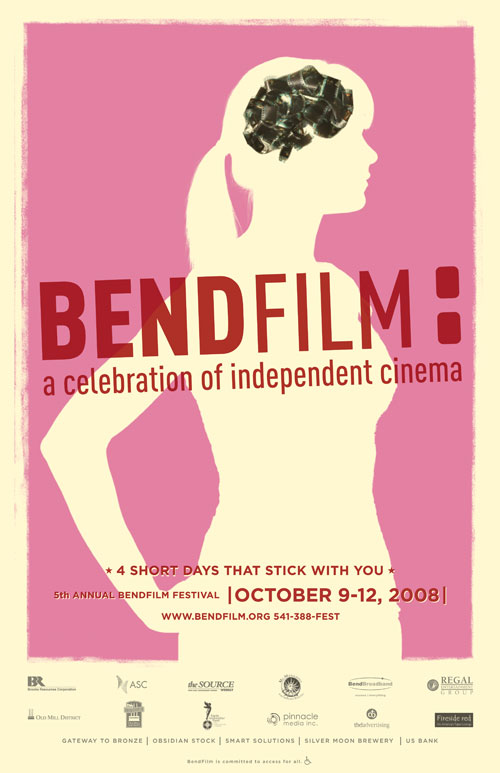

Other sponsors followed and in October 2004 the first BendFilm festival kicked off.

It quickly gained national buzz and comparisons to Sundance, attracting top independent filmmakers including Gus Van Sant and John Waters and screening notable films like the 2005 documentary Born Into Brothels, which went on to win an Academy Award. It didn’t hurt that the festival awarded filmmakers cash prizes — $10,000 in 2004, $50,000 by 2006.

BEHIND THE SCENES How some Oregon film festivals got their start.PORTLAND LATIN AMERICAN FILM FESTIVALLaunched 2007Maria Osterroth Sussman was homesick and bored after quitting her job in Mexico City as a business journalist and relocating to Portland with her husband, realtor Judah Sussman. So she turned to film to connect with her home country, organizing LAFF.“It’s not just that I missed family, but the culture, the activities, my job,” she says. “I never imagined I could miss a job the way I missed it.”For the first fest, she scrounged up $700 from friends and won a $1,000 grant from the Multnomah County Cultural Commission. But most of the support, $5,000, came from her husband.The festival screened noted films from Latin America, attracting 2,000 attendees. Now sponsors are signing on.POW FEST – PORTLAND WOMEN’S FILM FESTIVALLaunched 2008Tara Johnson-Medinger has been down the festival road before. Before POW Fest, she organized Portland’s 10 or Less Festival.But after six years, she turned her attention to films by women.Medinger is financially supporting the festival through her film company Sour Apple Productions, which she runs with partner Stephani Skalak.She’s hopeful that once the economy picks back up, sponsors will sign on.“For the next couple of years, it’s kind of like starting a small business,” she says. “It just takes time.”

|

More than 12,000 locals and tourists crowded downtown Bend theaters to catch films at the three-day fest in 2006. The following year, organizers were predicting 18,000 would show. The festival budget ballooned to $494,000 as area developers and builders happily sponsored, eliminating the need for organizers to apply for grant money.

What happened next is all too familiar.

By the time the October 2007 festival rolled around, Bend saw the first signs of trouble. Attendance was down and some sponsors cut back donations, leaving the organization with a budget shortfall.

Then in 2008, the housing market tumbled, taking a swath of festival sponsors with it and dragging BendFilm’s budget down to $287,000 — a $200,000 decline in one year.

Like other festivals throughout the state and elsewhere, BendFilm organizers were forced to reorganize to survive.

BendFilm is one of a number of festivals started in Oregon over the last decade, part of a worldwide trend driven by filmmakers and a growing interest in independent film.

The Film Festival Summit, an international trade organization for film festivals, estimates that there are more than 3,500 festivals worldwide. In Oregon there are at least a dozen, most started in the last decade when money was easy to come by. Stocks were up, real estate was up and businesses had money to give to the nonprofits that run festivals.

Many festivals were started by film buffs, others by community organizers who saw it as a way to bring out locals and spur downtown spending while adding some Hollywood glitz to their region. Some have used them to show off their part of the state to potential filmmakers for future film productions.

Whatever the reason, like everyone else film festivals are facing sharp cutbacks. Most are run as nonprofits and rely on a mix of public and private grants, corporate sponsors and ticket sales to get by.

BendFilm’s sharp decline last fall was a wake-up call to organizers at the state’s other festivals.

“Bend was held up as this festival that was doing well and then things appeared to be tough,” says Brenda VanDevelder, who runs the much smaller da Vinci Days Film Festival in Corvallis, which also struggled to attract sponsors to its March festival.

The Ashland Independent Film Festival, a critic’s favorite, had to slash this year’s budget 20% to $290,000 as major sponsors from years past faced falling revenues and cut back on donations. The festival’s executive director, Tom Olbrich, wouldn’t name them, but a review of sponsors this year vs. 2008 showed that Harry & David, the Stratford Inn, Ashland Food Co-op and Starbucks were among those to drop down to lower sponsorship levels. On top of that, Ashland’s grant income fell by $55,000 as grant organization endowments fell with the stock market.

To make its budget this year, Ashland raised ticket prices and membership fees and cut salaries, office expenses and its budget to fly in filmmakers for the festival. “There was no fat when we made cuts,” Olbrich says. “It was a challenge to carry out [the festival].”

The Salem Film Festival’s income was off 25% for its April event. To keep from losing sponsors, Salem lowered its donation levels, allowing businesses to sponsor a film for as little as $500.

They’ve also expanded their festival from three days to 10 in a bid to boost ticket sales by allowing attendees more than one chance to catch a film.

The much smaller Portland Women’s Festival, POW Fest, saw a near complete decline in cash donations and had to rely on in-kind donations, where a service was provided in return for advertisements at the festival.

In Bend, donations from contractors and realtors have almost completely dried up, and this year’s budget is down to $154,000, based on expected income, says BendFilm board president Jim Bailey. (Founder Merritt left in 2006, relocating to Portland.)

|

Bailey says they have the financing to hold a 2009 festival, though likely without extras like a filmmaker opening reception. In January, they cut three-quarters of their staff, getting rid of the executive director position, and moved to cheaper offices.

This year, they’re relying on an army of volunteers and in-kind donations from past sponsors who can’t afford to donate money.

“Basically what it’s doing is it’s causing both our organization as well as our supporters to be pretty creative in how we approach it,” Bailey says.

What does it matter if a city has a successful film festival? Restaurants, hotels and local businesses tend to be the leading financial supporters of film festivals, seeing them as a way to draw people downtown where they might stop to eat or shop after catching a movie. But the economic impact on an area can be hard to track. The state’s largest festival, the Portland International Film Festival, doesn’t even know how much spending it generates for the area, says Bill Foster, executive director of the Northwest Film Center, which runs PIFF.

Many of the regional festivals have aligned themselves with their local tourism office to promote their festival beyond Oregon borders.

|

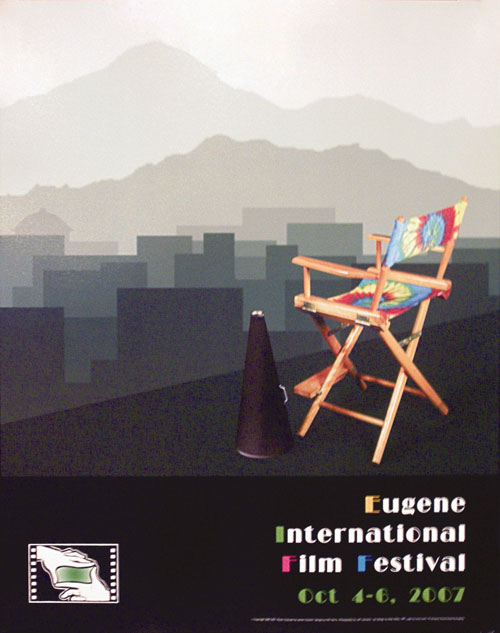

The 3-year-old Eugene International Film Festival seems to attract the biggest percentage of tourists; 58% of its 2,000 attendees came from out of state, according to a report by the EIFF and Travel Lane County tourism bureau. Most of those tourists stay an average of six days, two days longer than the festival runs.

“It really does show people coming into the area and they’re out and about doing sightseeing as well,” says Travel Lane County community relations manager Lisa Lawton.

The 2008 festival generated $450,000 in spending, but EIFF president Mike Dilley says getting filmmakers to return to make a film in the area, one of EIFF’s goals, would give the area a much more significant economic boost.

At other festivals, theater seats are mostly filled by locals.

|

About 77% of Bend’s attendees are from Bend these days. In Ashland, 20% come from 50 miles or more outside the city. It’s unclear how many stay overnight at hotels.

“I am a big fan of the Ashland festival,” says Karolina Wyszynska, director of sales and marketing at the downtown Ashland Springs Hotel. “It’s great for the local community but it does not bring revenues to our hotel.”

Ashland Springs sponsors the festival, putting up filmmakers in exchange for advertisements in the festival program, hoping to bring in overnight visitors. “I’m really hoping it’s going to happen one day like Sundance,” Wyszynska says.

Katharine Flanagan, marketing director with the Ashland Visitors and Convention Bureau, says the film festival is targeted at a more niche market and doesn’t attract the crowds of the Shakespeare Festival the city is known for, nor do they attract the crowds of the smaller festivals like the A Taste of Ashland food fest or the holiday Festival of Light Celebration.

It does increase foot traffic to restaurants in a “shoulder season” like April, when few tourists visit, she says.

Ashland organizers estimate the festival generates nearly $1 million in local revenues, with locals spending an average $12.50 a day and visitors spending $122 on average. Olbrich says visitors do stay in town, but it can be hard to track which visitors are there for the festival. This year organizers asked attendees where they stayed to get more detailed information.

Many organizers are hopeful that even during the recession, festival goers will continue to turn out, just as they are at movie theaters, which saw a 17% jump in box office revenues for the first quarter of 2009.

The long-running Portland film fest has attracted full-capacity crowds of 31,000 for the last two years and is even considering expanding.

The Da Vinci Film Festival in Corvallis, split off for the first time this year from the summer Da Vinci Festival, attracted 500 attendees, more than attended the film festival when it was part of the larger event.

|

Ashland’s Olbrich says attendance was almost even with 2008, with just over 6,000 attendees this year. Ashland sold 16,000 tickets, down 1,000 from 2008, but raised prices by $1, so revenues held.

“It turned out remarkably well given the economy,” he says.

Salem’s attendance also held steady after slipping in 2008 to 4,000 attendees, down from 4,500 in 2007, says organizer Loretta Miles, who also owns the Salem Cinema, where the festival is held. It helped that the Salem Cinema opened in its new location in downtown Salem for the festival.

Salem also brought in a number of filmmakers, which helped sell tickets. It’s something Ashland and Bend and other festivals are doing less of because they don’t have the budget to pay for travel.

Megan Mylan, who won the Academy Award this year for her documentary Smile Pinki, screened the film at three Oregon festivals, but only attended Salem, the town she grew up in.

|

“[Film festivals are] where you really get to connect with an audience,” she says.

Part of the allure of having a festival is bringing a little Hollywood glamour to an area.

Having noted films and filmmakers in town is exciting, Terri Mintz, BendFilm director of operations says. When the film 10 Questions for the Dalai Lama played the 2006 fest, people lined up around the block to see it and the director, Rick Ray, was so happy about the response he walked up and down the line taking pictures. “Filmmakers are treated well in Bend and so well received and so enthusiastic about being here,” she says.

While celebrities also draw people into downtown Bend during a slow season, city manager Eric King says the economic benefit is hard to quantify.

There’s one reason other than money that makes having a film festival attractive: It gives a city or a region a more cultured image.

Bend surveyed 7,000 residents recently about their vision for the city in the coming decades and respondents overwhelmingly listed BendFilm as key to keeping the city livable and unique, King says. “It gives the city character,” he says.

Boosters say it’s reason enough to make sure their festival survives. As much as Bend residents want their skiing and hiking, many miss the culture of the larger cities they left behind.

Film festivals across the state struggle to stay on the red carpet.

Film festivals across the state struggle to stay on the red carpet. EUGENE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL

EUGENE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL The Portland International Film Festival aims to incubate the local film industry. This year it hosted Coraline from Laika.

The Portland International Film Festival aims to incubate the local film industry. This year it hosted Coraline from Laika. From left: At this year’s Portland International Film Festival were Phil Knight, actress Teri Hatcher (one of the voices in Coraline) and Travis Knight, whose company, Laika, created Coraline.

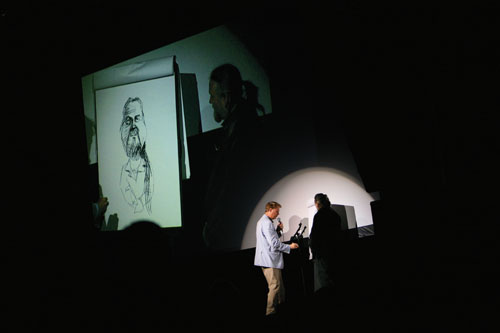

From left: At this year’s Portland International Film Festival were Phil Knight, actress Teri Hatcher (one of the voices in Coraline) and Travis Knight, whose company, Laika, created Coraline. This year’s Ashland Independent Film Festival featured Oscar-nominated animator Bill Plimpton.

This year’s Ashland Independent Film Festival featured Oscar-nominated animator Bill Plimpton. A panel of documentary filmmakers takes questions.

A panel of documentary filmmakers takes questions. Crowds gather at the Varsity Theater in downtown Ashland.

Crowds gather at the Varsity Theater in downtown Ashland. Desierto Sur was part of the Portland Latin American Film Festival held in May this past year.

Desierto Sur was part of the Portland Latin American Film Festival held in May this past year. Ruby Rocket, Private Detective was the Best Short Short Animation film at the Eugene International Film Festival.

Ruby Rocket, Private Detective was the Best Short Short Animation film at the Eugene International Film Festival.