Community-owned heating plants are an old idea garnering new enthusiasm as climate change and alternative energy needs make their 19th century technology right for the future.

Community-owned heating plants are an old idea garnering new enthusiasm as climate change and alternative energy needs make their 19th century technology right for the future.

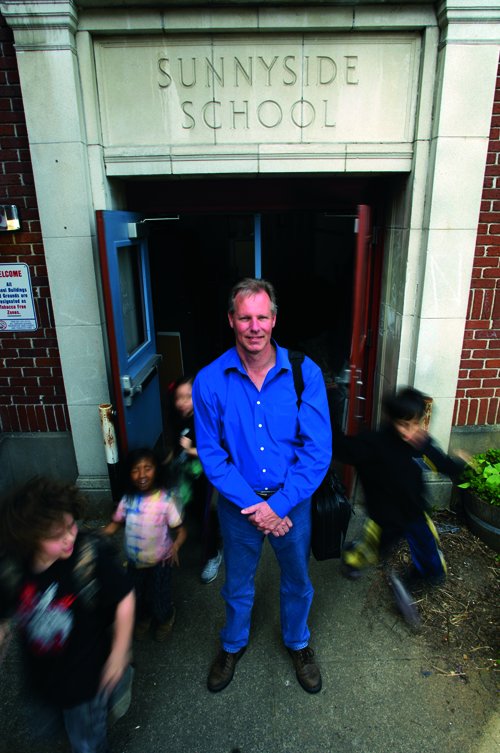

John Sorenson wants to build a community-owned heating plant in Southeast Portland’s Sunnyside neighborhood, powered by the sun and biomass. |

Community-owned heating plants are an old idea garnering new enthusiasm as climate change and alternative energy needs make their 19th century technology right for the future.

By Linda Baker/Photo by Michael Halle

When John Sorenson moved to Portland from Alaska in 2001, the 55-year-old carpenter did what any self-respecting transplant to Green City, USA, would do. He converted his truck to run on waste vegetable oil and reduced his household energy use by 70%. But Sorenson still wasn’t satisfied. “The question was: How much did I contribute to cutting climate change?” he asks. The answer: not so much. “You can’t get there as an individual,” he says.

Eight years later, the tall, sandy-haired Sorenson has developed an ambitious collective strategy for reducing carbon dioxide emissions. The mission? To build a community-owned heating plant in Southeast Portland’s Sunnyside neighborhood, powered by the sun and biomass. Heating, cooling and domestic hot water consumes a “mind blowing” 70% of household energy use, says Sorenson, now the executive director of Neighborhood Natural Energy, a local nonprofit.

He estimates the “SunNE” plant, which would provide heat to about 500 homes and businesses, could cut carbon dioxide emissions by 1,000 tons each year — the equivalent of taking 250 cars off the road.

What Sorenson is proposing is called district heating and it’s not a new idea. About 60% of all homes in Scandinavia are tied to community heating systems. In the U.S. they have served commercial districts in cities such as New York and Philadelphia for more than a century. Now a 19th-century technology is getting a second look, this time as a global warming solution. In Portland, neighborhood thermal districts show up as a key action in the city’s recently updated climate protection plan, which aims to reduce local greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2050. In addition to the Sunnyside project — the first in the country to spring up in an existing residential neighborhood — Sorenson, in parallel with the city and private developers, is working on a similar plan for the North Pearl district. Yet another has been proposed for the Lloyd Crossing area.

The return of district heating is part of a larger 21st-century story. Today, everything old is new: streetcars, bicycles, backyard food gardens, and now district heating. Neighborhood renewable energy plants also fit into the “buy local” philosophy, which in Portland has become something of a categorical imperative. Of course, just how the proposed thermal districts will be funded nobody — not the city, not Sorenson — can say. But Sorenson, a man driven by passion, is undeterred. “If you are an investor with money, where do you want to put it?” he asks. “Into something volatile or something secure? We have a great story, about the grassroots, innovators and utilizing local resources.”

On a recent evening, Sorenson recounted the SunNE story in the Pearl District law offices of Perkins Coie, where the local chapter of The Indus Entrepreneurs (TIE) was holding its monthly meeting. During the talk, a TIE member inquired: “Are you going to deliver power to the people?” “God no!” responded Sorenson, unleashing a wave of laughter. The SunNE plant wouldn’t provide electric power, he explained, but it would displace the natural gas and electricity used for domestic space heating and hot water. District thermal technology isn’t rocket science, Sorenson added. Basically, a central plant produces hot water (the conventional medium was steam), which is then delivered via underground pipe to participating buildings. Inside the buildings, heat exchangers draw energy from the water to meet space heating and hot water needs. The water is then returned to the plant and recirculated in a closed-loop system.

To that integrated design scenario, Sorenson has added innovation. The idea is to locate the plant at Sunnyside Environmental School, where boilers running on biomass would replace the school’s 108- year-old fuel-oil boiler. Rooftop-mounted solar thermal panels would provide another heat source. Solar thermal systems require storage, so Sorenson decided to locate the million-gallon storage tanks underneath the school playground. “The school goes carbon neutral and receives income by leasing the playground’s subsurface space,” he sums up. “The community benefits, and the environment also receives a benefit.”

To understand exactly what those benefits are, consider that a central heating plant eliminates the need to install, and pay for, boilers in each building or a furnace in every house. There are also inherent fuel efficiencies associated with using a single plant to heat multiple buildings or dwellings at the same time. “Economies of scale are the drivers of district heating systems,” says Mark Kendall, senior policy associate for the Oregon Department of Energy.

Alternative energy adds yet another benefit. Historically, district heating plants have been powered by fossil fuels. The 21st-century innovation is to substitute renewable sources, although some projects are ahead of the game. In Oregon, the city-owned Klamath Falls geothermal heating district has served downtown businesses for 25 years. The nonprofit-owned District Energy of St. Paul in Minnesota got its start in 1993 and now serves 185 downtown buildings on a 70/30 mix of biomass and fossil fuels. The system is about 20% more efficient than a building-based approach and has reduced emissions by 280,000 tons annually, says District Energy president Anders Rydaker. A recipient of the International District Energy Prize, Rydaker was one of the first people Sorenson called for advice when he was first calculating SunNE’s energy loads, biomass requirements and other systems challenges. “Anders does those calculations in his sleep,” Sorenson says.

Unlike community thermal projects in Scandinavia, central plants in the United States are limited to business districts or university and hospital environments. SunNE aims to change all that. The goal, Sorenson says, is to create a green utility model for the nation’s older urban areas, where millions of homes are “now exhausting energy.” He targeted Sunnyside as a pilot because of the neighborhood’s history of community activism. In the 1990s, when Enron was collapsing, Sunnyside residents tried, but failed, to form a neighborhood utility district. “Would you go into a subdivision of oil and gas executives?” Sorenson asks. “Sunnyside was low-hanging fruit.” It was a good call. Last summer, a survey sponsored by environmental group Focus the Nation showed that 85% of Sunnyside residents supported the SunNE concept, even if rates were 20% higher than the local thermal utility.

“We have seen hundreds of neighbors come to meetings and offer their support,” says Tim Brooks, president of the Sunnyside Neighborhood Association. “There are clear environmental benefits, and also some other benefits, such as community initiative and collaboration, local partnerships, and local control.” The Portland Public Schools district supports the idea. So have U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer and other elected officials.

The SunNE survey raises questions about the relationship between local gas and electric utilities and district thermal systems, which are not regulated by the state’s Public Utility Commission. In St. Paul, Xcel Energy sells natural gas to District Energy, but the utility also competes with the nonprofit for customers. (So far, District Energy is winning, claiming 80% of downtown real estate.)

It’s too early to say how NW Natural “would play” in the proposed projects, says Bill Edmonds, director of environmental policy for NW Natural, which serves Sunnyside. But the company could conceivably provide backup fuel or install the system piping, he says, adding: “The world is changing, and we will be changing with it.” In 1998, PGE built a natural-gas-powered central plant serving the Beaverton Round, now owned by the City of Beaverton. The utility doesn’t have any current plans to invest in district thermal projects, says Joe Barra, director of Customer Energy Solutions.

Sorenson is planning a June district heating tour of Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark (the birthplace of his paternal grandfather), and waiting to hear if he would receive a state grant to pay for a SunNE feasibility study. He is realistic about the challenges, including the cost and the headaches associated with ripping up streets in an existing neighborhood.

He also has other projects up his sleeve. The City of Portland hopes to site a community thermal system in the North Pearl District, and Sorenson wants Neighborhood Natural Energy to develop it. In fact, he’s already identified an underutilized community resource to power the project: waste beer mash from the area’s 40-plus microbreweries. “We’d call it BGE, Brewers’ Gas & Electric,” Sorenson says.

Last fall, the city conducted a feasibility study showing a North Pearl system would reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 10% compared to a building-by-building approach — another 75% assuming a renewable fuel source. District heating is part of the city’s emerging “eco district” approach to sustainable development, in which water, transportation and energy issues are addressed on a district-wide instead of building scale, says Michael Armstrong, deputy director of the Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. Unlike smart grid technology, district heating is a low-tech response to global warming, Armstrong says. “But we’re going to need every high-tech gadget and do all the low-tech ones as well.”

Sorenson, who works out of an office on Northeast Sandy Blvd. — donated by a local realtor and SunNE convert — couldn’t agree more. “The question is, how can you get the most environmental benefit for your money?” he asks.

The answer is rooted in social as well as technological change, he says. He points out that solar thermal storage requires sheer mass to work; try to capture the energy from a single homeowner’s rooftop array, and the heat simply dissipates into the ground. Renewable energy tax-credit packages also favor individuals banding together as a group. “You start to realize how much more we can accomplish if we cooperate,” Sorenson says. “District energy is an elegant community-based solution.”