Oregon’s $18 billion underground economy is exploding as the recession pushes more transactions under the table.

Oregon’s $18 billion underground economy is exploding as the recession pushes more transactions under the table.

The taxman loses and the entrepreneur thrives.

By BEN JACKLET

The out-of-work car mechanic needed cash, so he started making house calls around the Portland metro area. He discovered quickly that he could easily undercut the prices of the dealership where he formerly worked by more than a half. Since he has no shop to lease, maintain and pay taxes on, his only expense is the gas he burns driving to jobs. He began marketing his under-the-table services for free online on the recommendation of his mom, a massage therapist who lines up clients through Craigslist. “I can undercut the other guys easily,” he says unapologetically. “I have a valuable trade skill that everybody needs because everybody has a car. And I save people astronomical amounts of money.”

| ||||||||

The same principles apply for the computer genius willing to show up at your house and revive your virus-ravaged machine for $30 an hour, the sewing and mending wizard cashing in on the new frugality, the day laborer who hops into a pickup truck driven by someone he has never met and agrees to work for $10 an hour, and the plumber who offers cash discounts and writes down nothing.

The theme that binds these people is that they earn income without paying taxes on it. Whether they consider themselves part of Oregon’s $18 billion underground economy or not, they are. That puts them in the same sweeping category as the Lake Oswego business owner who sets up a network of shell companies to funnel a million dollars into his personal accounts, the third-generation bookie who is rarely seen without his briefcase full of cash and the drug kingpin who lures an undocumented immigrant to Salem with the promise of a job and threatens to have her family killed if she does not obey him.

Defining Oregon’s underground economy is simple: all goods and services not reported to the government. Quantifying it is another matter. The underground economy is inherently murky, fluid, decentralized, a mishmash of legitimate service providers such as nannies and gutter-cleaners, complex pass-through organizations such as S Corps and LLCs, and ruthless criminals profiting from sex and drugs and fraud. Portions of the shadow economy, as it is sometimes called, are indeed shadowy; others are fairly harmless and even logical when you consider the state of Oregon’s job market.

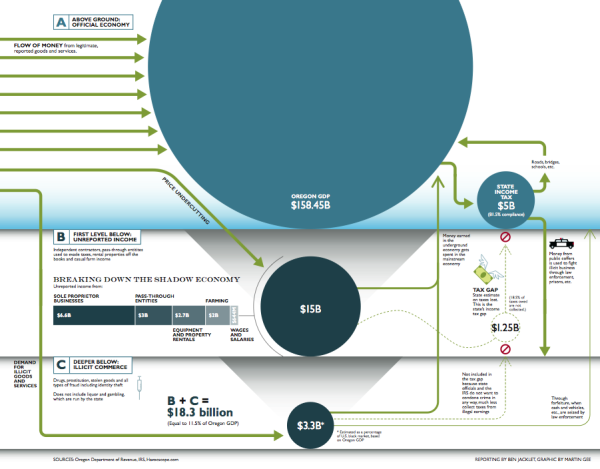

According to a recent report by the Oregon Department of Revenue, approximately $15 billion of income earned by independent contractors, S Corps, farmers, landlords and others with limited third-party oversight goes unreported each year. Add to that sum a rough estimate of Oregon’s $3.3 billion black market for illegal drugs and gambling, prostitution, stolen and pirated goods, identity theft, and other scams. The resulting figure of $18.3 billion, or 11.5% of Oregon’s GDP, is a solid approximation. It’s also a rather staggering amount, comparable to annual global revenues for Nike, Oregon’s largest company.

click on image to download larger PDF version |

Economists expect that figure to grow. “More people tend to move over to the underground economy as the regular economy goes down,” says Morton Paglin, a professor emeritus of economics at Portland State University who has published peer-reviewed studies of the underground economy. “As people lose their jobs and are unable to find new ones, a certain percentage of them will scratch around on their own for some form of employment, and they are unlikely to report their earnings because that would eat into their unemployment.”

That would be bad news for Oregon’s public sector, which relies heavily on income tax because of the lack of a sales tax. It could also create problems for above-ground businesses scrambling to survive vicious price wars as consumer confidence plummets. In addition, an expansion of the underground economy can weaken official statistics because large amounts of economic activity are missed.

On the upside, an expanding underground economy can create opportunities that reward people for their ingenuity and hard work.

Entrepreneurs who operate off the books can provide services very cheaply. Contractors hire them to reduce labor costs. Consumers hire them to save money on household maintenance and computer repairs. The Internet makes it easier than ever for them to conduct mass-marketing campaigns for free, anonymously if they desire. These self-starters have found an ideal conduit for their businesses in Craigslist, which generates more than 12 billion page views per month globally. Traditional job postings are drying up at portland.craigslist.org, but independent service providers of all varieties are proliferating. A typical day brings 2,000 new Portland Craigslist ads for services ranging from mobile manicures to sensual massage, as compared to about 200 new listings for jobs. The breadth of the services offered is substantial: music transcription, gutter cleaning, web design, engine rebuilding, dog running ($6 per mile), hair braiding, landscaping, furniture moving, photography, escort services, and on and on. The site’s list of mainstream jobs seems thin by comparison, with several entries reeking of scam.

Not all of the entrepreneurs marketing their expertise through Craigslist in Portland, Eugene, Medford and Bend are evading taxes, but a significant percentage are, particularly those who blatantly write “cash only” in their ads, offer “flat rate” discounts to those who pay in cash, or sell large volumes of stolen or pirated goods, especially electronics. Several of the dozen or so anonymous entrepreneurs interviewed for this article admitted freely to underreporting taxes or ignoring them altogether. “I don’t pay taxes,” said one woman who juggles gigs providing makeovers for brides-to-be, research papers for slacker students and in-home therapy for autistic children.

Some of these entrepreneurs have real experience and skills; others exaggerate their credentials to land jobs. Most say that competition is heating up; the talent pool is growing as layoffs spread, and prices are falling. As one seemingly well-qualified iPhone developer says in his online ad, “Although revenue sharing arrangements are welcome, I’m currently in need of cash.”

Who isn’t? With economic gloom spreading, the temptation to gather cash off the books can be powerful. Business owners who deal in cash are being advised to hoard it in preparation for hard times. Servers who rely on cash tips, such as waitresses, baristas, street musicians and exotic dancers, are trying to make a living in the face of a tidal shift in consumer spending. Cash tips are supposed to be reported as taxable income, but enforcing that mandate at thousands of coffee shops, taco trailers and strip clubs is no simple matter.

The same applies to casual immigrant labor. An estimated 175,000 undocumented immigrants live in Oregon. Many migrated to work in the fields and later shifted into urban areas to capitalize on the construction and restaurant boom, often working under the table as cooks, roofers and landscapers. Some have created off-the-books businesses that skimp on workers’ comp insurance and payroll tax to offer prices that are hard to beat.

The government’s official position on all varieties of skimming, ducking and downright evasion, of course, is consistent. As IRS spokesman Bill Brunson warns, “If you cheat on your taxes you’re going to face consequences.”

Economists take a more nuanced view. Studies have credited off-the-books business with injecting cash flow and entrepreneurial vigor into economies that have been burdened by excessive bureaucracy, as in Italy, where the underground economy is estimated at about 30% of GDP.

“The underground economy can stimulate employment and output,” says Paglin. “If you really cracked down on under-the-table commerce you would be condemning a significant portion of the labor market to unemployment or criminal activities.”

Tax compliance estimates compiled by public agencies completely ignore income from illicit trade. As Derrick Gasperini, a spokesman for the Department of Revenue, says, “We wouldn’t want to condone those activities in any way by suggesting that they should be taxed.”

Still, to omit illicit earnings while calculating the underground economy would be a mistake. Moises Naim, editor of Foreign Policy magazine, makes a persuasive case in his book Illicit that globalization has enabled illicit trade to spread into every nation as a significant business force that grows more complex and sophisticated each year. This same trend feeds Oregon’s underbelly demand for drugs, prostitution, and pirated and stolen goods. As Naim emphasizes in his writings, the trend is economic in nature, and the biggest players operate as diversified multinational businesses.

Anyone who doubts the economic impact of Oregon’s black market should spend an hour with Alan Peters, assistant special agent in charge of the Portland Office of the FBI, as he weaves an ominous narrative spiced with references to online prostitution rackets, human trafficking conspiracies, Mexican drug gangs, Romanian identity merchants, Russian mob health care fraud scams, the market for stolen baby formula, the theft and resale of cell phones and laptops, and any other scam you might imagine, plus a few you’ve probably never considered.

Crime numbers have been dropping nationally and in Oregon, but Peters worries that the failing economy will reverse that trend. “We’re going to see crimes of desperation increase,” he predicts. “Prostitution, bank robberies, fraud scams, all of those will pick up as people get more desperate. The organized groups will also become more desperate, because someone’s got to have cash on the other end of the transaction for the deal to go through. It’s simple economics, whether we’re talking about illegal or legitimate activity. It’s supply and demand.”

Illicit operations are inherently difficult to track, but the occasional large-scale bust offers a window into an elaborate web of for-profit criminal enterprise. Consider briefly the following examples, each of which resulted in guilty pleas in U.S. District Court in Portland:

• A web of 29 drug runners was moving 70 pounds of Mexican heroin and methamphetamines per month from Mexico into the Willamette Valley. One of the ring’s kingpins, Arturo Arciga, used his Springfield auto repair business as a distribution center.

• Luis Sandoval-Arrellano was caught growing more than 7,000 marijuana plants with a value of $700,000-$2 million in a remote canyon in Wasco County.

• James Tobias Wolf was arrested on a train passing through Albany with approximately $200,000 worth of Oxycontin pills on him.

• 20 people were arrested in Portland and Woodburn in a massive bust in which authorities seized 21 vehicles, 36 pounds of methamphetamine, 24 firearms and $163,000 in cash.

Law enforcement officials are also battling an expansion of the second-largest element of the black market, prostitution. Neighborhood groups in Portland are organizing against a resurgence of streetwalkers along 82nd Avenue, and a prostitution sting bust in Medford arrested five women who allegedly marketed their services as “escorts” through medford.craigslist.org.

Of the 2,000 or so ads posted under the category of services daily at portland.craigslist.org, about 200 are selling “erotic services.”

Profitable illicit enterprises are designed to operate in secrecy. So are plenty of mainstream businesses that deal in legitimate goods and services but go to elaborate lengths to conceal earnings. The Department of Revenue estimates that more than $3 billion per year earned by pass-through entities goes unreported each year because confusing, multi-layered ownership structures enable business executives to hide transactions and disguise identities.

In one recent IRS case, Mark Henriksen, a principal of Lake Oswego-based Applied Technical Systems, pleaded guilty to evading taxes on more than $1 million in income by funneling bonus checks through shell companies he created and using corporate checks to pay for personal spending. In another case, Portland architect Jeffrey Carrithers admitted to using two different Social Security numbers to camouflage his earnings, avoiding nearly $100,000 in taxes. Both men are scheduled to be sentenced in the coming weeks for income tax evasion.

Those two criminal convictions were based on investigations of tax returns dating back as far as 1998. The game has gotten a lot trickier since then. Kenneth Hines, IRS special agent in charge of the Pacific Northwest, says the fraud schemes he investigates are constantly evolving as technology advances. “It’s so instant now,” he says. “Identity theft can happen so quickly. These guys can set up this system where they rob you blind without you noticing a thing.”

Online hucksters also have come a long way from the Nigerian sob stories of the 1990s. A common technique today involves impersonating a figure of authority in order to demand sensitive information such as Social Security numbers, bank accounts and dates of birth through fraudulent websites such as irs.com and uscourts.com. A February alert from the Oregon Attorney General’s office warned of a scam threatening consumers with false subpoenas for avoiding jury duty, to pry away sensitive information for identity theft. In March the AG’s office issued another warning of a slew of loan modification schemes capitalizing on financial turmoil, followed by a fresh crop of “economic stimulus grant” scams. According to the AG’s figures, written complaints from citizens are up 44% over last year.

A dramatic rise in fraud, crimes of desperation and under-the-table dealings may paint an overly grim narrative. It brings to mind The Onion’s deadpan recommendation that Americans should “stock up on kerosene and spears.” It hasn’t gotten quite that bad in Oregon. We aren’t Nigeria, where the shadow economy is estimated to be 77% of GDP and 400,000 barrels of oil go missing each month. Even if 18.5% of statewide earnings go unreported, that means more than 80% of Oregonians are playing by the rules and paying their taxes. But if the shift from aboveground to underground accelerates, the consequences will be serious for both the public and private sectors.

The IRS estimates the national tax gap (the difference between what is paid to the federal government and what is owed) to be $290 billion. The Oregon Department of Revenue calculates the state’s income tax gap at $1.25 billion. That is money that could be put to use boosting the economy, buoying vital employers who are sinking amid the recession, recruiting new companies, encouraging startups and providing services to people losing their jobs and homes.

In the view of Peters of the FBI, the challenge is to “find that money and bring it back into the legitimate system. Especially when we are planning to spend all this money to get the economy going again. Something has to backfill all of these new expenditures.”

That’s true. But at the same time, a recent survey conducted by the department of revenue indicates that Oregonians are feeling ambivalent about taxes. Of the 1,229 taxpayers who completed the department’s survey in the summer and fall of 2008, more than half (51%) felt they were paying too much for the services they received, while 33% felt they pay the right amount.

The number of respondents who considered Oregon’s tax system to be unfair narrowly outnumbered those who found it fair. And 56.8% of the Oregonians who responded to the survey agreed either strongly or somewhat with the statement that more people than ever are earning income in cash to avoid taxes.

That last finding would seem to indicate that most Oregonians are aware of the rise of the underground economy and at least somewhat accepting of it — maybe not the sordid side of the equation, with its pimps, heroin needles and email scams, but rather the entrepreneurial idea of upstarts using ingenuity to beat out the established competition.

In that sense, the newest development with the underground economy may be that it isn’t so far underground any more. People are moving underground to find opportunities that are becoming increasingly elusive above the surface as the mainstream economy flounders.

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]