Oregon’s economy may be thriving — and according to at least one economist, food costs less today than it did 30 years ago — but there’s a ready market for the increasing number of discount grocers in the state.

Bargain business

Bargain business

Discount grocery chains scoop up shoppers, and market share, as new stores open throughout the state.

By Jeanie Senior

Oregon’s economy may be thriving — and according to at least one economist, food costs less today than it did 30 years ago — but there’s a ready market for the increasing number of discount grocers in the state.

Clearly, not everyone is doing their grocery shopping at pricey Whole Foods. Or even at Safeway, with its newly gussied-up “lifestyle” format. Many are heading instead to discounters such as WinCo Foods, Grocery Outlet and Price Less Foods, where the focus is on low price, not high style.

Grocery retailing once was dominated by supermarket chains so similar that shoppers moved freely between, say, Albertsons and Safeway. But now, “There’s a long list of new entries doing it differently than the traditional grocery,” says Bert Hambleton, president of the Seattle-area grocery-consulting firm Hambleton Resources.

“It’s all about moving away from the center,” he says. Whether it’s upscale stores such as Whole Foods and New Seasons, or discounters, “every one of the segments that moves away from the middle of the conventional grocery spectrum is growing.”

As a sign of the growing discount market, Save-A-Lot entered the state this year, opening its first two stores in the Portland area; it recently announced a third store will open in Springfield, and it plans to steadily increase its Oregon presence.

“These are big populations underserved by existing retail,” says Steve Burkhardt, vice president of strategic planning for the Earth City, Mo., chain, which now operates in 42 states, explaining its expansion into the Pacific Northwest. “We’re looking for new markets.” The chain now has more than 1,160 stores nationwide and annual sales of more than $4 billion.

Another growth spurt has come from Grocery Outlet, headquartered in Berkeley, Calif., which this year opened three new Oregon stores in Albany, Prineville and Woodburn. That makes a total of 28 Oregon stores, more than any discount grocery chain in the state, and the privately held company still is looking for more locations.

“We’re actively in the market all the time,” says Jon Wylie, vice president of marketing for Grocery Outlet, adding “Oregon and Washington have been great states for us.” The company has 124 stores in six Western states and one in Hawaii, with total yearly revenues of $600 million. Stores average about 20,000 square feet and annual per-store sales average about $5 million.

Oregon’s other major discounter is Boise-based WinCo Foods, which has 16 stores in Oregon. In contrast to Grocery Outlet and

Store definitionsConventional supermarket: The original supermarket format offering a full line of groceries, meat, and produce with at least $2 million in annual sales. These stores typically carry approximately 15,000 items, offer a service deli and frequently a service bakery. Superstore: A larger version of the conventional supermarket with at least 40,000 square feet in total selling area and 25,000 items. Superstores offer an expanded selection of non-foods. Food/drug combo: A combination of superstore and drug store under a single roof, with common checkouts. These stores also have a pharmacy. Warehouse store: A low-margin grocery store offering reduced variety, lower service levels, minimal decor, and a streamlined merchandising presentation, along with aggressive pricing. Generally, warehouse stores don’t offer specialty departments. Super warehouse: A high-volume, hybrid format of a superstore and a warehouse store. Super warehouse stores typically offer a full range of service departments, quality perishables and reduced prices, e.g., Cub Foods. Limited-assortment store: A bare-bones, low-priced grocery store that provides very limited services and carries fewer than 2,000 items with limited-if any-perishables, e.g., Sav-A-Lot. Other: The small corner grocery store that carries a limited selection of staples and other convenience goods. These stores generate approximately $1 million in business annually. Convenience store (traditional): A small, higher-margin store that offers an edited selection of staple groceries, non-foods, and other convenience food items, i.e., ready-to-heat and ready-to-eat foods. The traditional format includes those stores that started out as strictly convenience stores but might also sell gasoline. |

Sav-A-Lot, WinCo has gigantic stores. “WinCo decided to go with size to make the price statement,” says consultant Hambleton. “WinCo is so big — 93,000 square feet, two acres under a roof.” Thanks to efficiencies of scale, Hambleton says, “They actually, objectively, have the lowest prices in the grocery business; lower than Wal-Mart.”

WinCo, which does little advertising, is intentionally low-profile, according to Michael Read, vice president of public and legal affairs for the employee-owned discounter. The grocer, whose roots are in Cub Foods and Ware-Mart, has 54 stores in Oregon, Idaho, Washington, Nevada and California, and annual sales estimated at $2.5 billion. The firm also has two huge distribution centers in Oregon, in Woodburn and Myrtle Creek. At least for now, Read says, most of WinCo’s future growth is aimed at California.

Other grocers with discount or warehouse stores in Oregon include Food 4 Less, owned by Fred Meyer parent Kroger, with markets in Coos Bay, Cove and Milton-Freewater. Family-owned C&K Market’s 51 stores in Oregon and Northern California include two warehouse store operations; it’s based in Brookings.

Price Less has markets in Myrtle Creek, Sutherlin, Winston and White City, and Shop Smart has stores in Harbor and Cave Junction.

There’s a tendency to include both Costco and Wal-Mart on the list of discount grocers. But Hambleton and other industry analysts point out that for both retailers groceries are only a part of their business model. “I would not immediately put then on a list of discount grocery stores,” he says. “Discounters, yes.” Still, groceries, sundries and fresh products account for 60% of Costco’s total sales — $31.1 billion a year.

OREGON’S FLOURISHING DISCOUNTERS RAISE INTERESTING QUESTIONS about the people who shop there. Is the stores’ burgeoning presence an indicator of growing poverty, an increasing number of middle-class residents in a budget squeeze, or lots of bargain-hunters?

OREGON’S FLOURISHING DISCOUNTERS RAISE INTERESTING QUESTIONS about the people who shop there. Is the stores’ burgeoning presence an indicator of growing poverty, an increasing number of middle-class residents in a budget squeeze, or lots of bargain-hunters?

The number of Oregonians who live at the poverty level (defined in 2005 as $16,090 annual income for a family of three) continues to climb. The poverty rate hovers around 12% of the population, and in some counties it’s far higher. According to 2003 state statistics, 18.3% of Malheur County residents live at the poverty line or lower; the rate is around 15% in Klamath, Josephine, Coos and Lake counties. At the same time, per-capita income in Oregon lags in the rural areas. In 2004, when per capita annual income was more than $35,000 in the Portland Metro area, it was less than $25,000 in a sizable portion of the state.

At the same time, consumers appear to be getting more frugal. A 2003 survey by the Food Marketing Institute, an industry organization, found “an ongoing consumer shift toward value retailers — not only for monthly stock-up shopping but for routine trips.” The same survey said stable food spending reflects both low inflation in food prices and cost-consciousness.

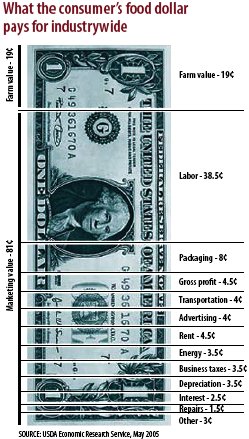

Hambleton, an economist, notes that food is cheaper today than it was 30 years ago, thanks to efficiencies in production, processing and transportation. “The average household today is spending 10% of its total income in the grocery store; 30 years ago it was 15%,” he says. Although he contends that there aren’t more poor people among food shoppers today, he adds, “To put it bluntly, yes, there are markets that discount groceries will fit better.”

Grocery Outlet’s Wylie, talking about the demographic the company seeks when it locates a store, clearly isn’t describing the upper-middle class. “We’re looking for a female maybe mid-30s and higher, mid- to lower income, although we have some locations that do very well where there’s a broad mix of incomes.” He says the chain’s stores normally do well “where there’s quite a bit of multifamily housing, families with children, and a good mix of minority and non-minority persons.”

Wylie tends to divide the chain’s customers into two groups. There are the “need” shoppers who are on a definite budget and shop for the 40% discount that Grocery Outlet says it averages. He calls the other group “treasure hunters,” people who view shopping there as a treasure hunt, finding big discounts on wine or imported cheese.

At the Beaverton WinCo recently, any treasure hunting that Jennifer Wabnitz was doing was strictly a hunt for bargains. She says she shops at WinCo for one primary reason: “Six kids.” But she could as easily answer “to save money.” She estimates she saves hundreds of dollars by shopping at WinCo for her children, ages 3 to 18, herself, husband Steve, and the family dog.

“A gallon of milk is $2 here,” Wabnitz says. “You really have to try hard to find it for that anywhere else. And we use six gallons a week.” She says WinCo’s lack of frills doesn’t bother her. “I don’t mind packing groceries to save money. They provide a cart. What more do you need?”

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]