Forget the storied orchards and iconic wind sailors. Dozens of tech companies producing everything from unmanned aircraft to solar energy are finding the Columbia River Gorge is the place to do business.

Forget the storied orchards and iconic wind sailors. Dozens of tech companies producing everything from unmanned aircraft to solar energy are finding the Columbia River Gorge is the place to do business.

|

The Gorge effect

Forget the storied orchards and iconic wind sailors. Dozens of tech companies producing everything from unmanned aircraft to solar energy are finding the Columbia River Gorge is the place to do business.

By Michelle V. Rafter

Picture Oregon’s high-tech hot spots and the bucolic riverside community of Hood River isn’t the first that springs to mind. But the Columbia River Gorge region, best known for orchards, wineries and windsurfing, steadily and without much fanfare has become home to an assortment of tech ventures in numbers strong enough they’re reshaping the very nature of industry in the area.

In little more than a decade, at least 50 aerospace engineering, electronics, Internet, computer hardware and software, and most recently, alternative energy technology companies have sprung up in and around Hood River and The Dalles and across the Columbia River in Bingen, Wash. Many companies in the so-called Gorge tech cluster are small, one- or two-person enterprises started by outdoors enthusiasts who wanted to work where they played. Several have grown big enough to gain regional or even national acclaim. The most notable is Insitu, the area’s largest high-tech employer and a venture capital-backed pioneer in the field of unmanned aircraft. Then there’s Google, which in 2006 opened a massive computer server complex in The Dalles that employs about 200 people, including some full-time permanent contract workers.

The impact of the Gorge tech cluster is visible everywhere. Tech companies are tucked into office buildings all over Hood River. During a four-year growth spurt, Insitu’s employee ranks have blossomed tenfold, to 240, forcing the company into 10 buildings in Bingen and nearby White Salmon. The company has started year-round internship programs to attract college grads, and helped fund robotics courses at several local high schools.

It’s also spawned several local spinoffs and supported a number of area subcontractors that in turn have hired workers who in bygone days would have picked apples or waited tables. Spurred by the area’s burgeoning wind-farm businesses, Columbia Gorge Community College in The Dalles is swamped with applications for a new renewable energy certificate program that’s graduating technicians into high-paying jobs. The college is also building a 10,000-square-foot satellite campus in Hood River to meet growing demand for classes there.

Such activities are one reason why unemployment in the five rural and historically poor Oregon and Washington counties that make up the Columbia Gorge area has fallen to half of what it was five years ago; 5.1% in August 2007 compared with 11.4% in December 2002, near the height of a statewide recession, according to Oregon and Washington employment departments. State and local agencies don’t specifically track technology sector jobs. But manufacturing and other private sectors — traditionally where most high-tech positions are counted — have added 1,145 jobs since December 2002, a 19.7% increase.

“It’s been huge on the regional economy,” says Bill Fashing, Hood River County’s economic development manager. “The influx of talent, the incomes these individuals are bringing into the community are significantly higher than the traditional average wage in this region. That’s extremely important to the long-term economic vitality of the community and the people who live here.”

|

What’s happening in the Gorge is a classic example of economic clustering, where a bunch of companies in the same industry benefit from being located near each other. The proximity lends itself to local partnerships and idea sharing. The downside is that companies work near competitors and employees get poached or leave to start their own gigs. But the positives outweigh the negatives. Because of the cluster, when sales reps or parts distributors come to town to see Insitu or other big companies, they stop at the little ones, too, says Arthur Babitz, a Hood River city councilman and co-owner of a two-person animation equipment company. “We’re on the map now.”

IF THE REGION’S TECH BUSINESS has a founding father, it’s Andrew “Andy” von Flotow, an MIT astronautics engineer and windsurfer who followed his bliss and moved to Hood River in the early 1990s. Von Flotow started an aeronautics systems supplier, Hood Technology, and convinced a few friends to follow.

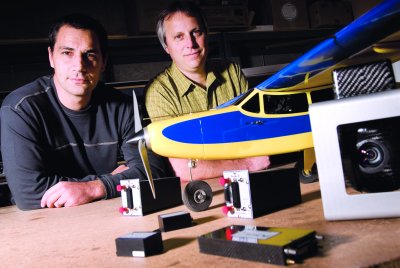

One was Tad McGreer, founder of Insitu, which opened in 1994 and gained industry acclaim four years later for flying the first unmanned airplanes across the Atlantic. Over the years, innovating engineers departed Insitu to start their own businesses, including Bill Vaglienti and Russ Hoag, who left in 1999 to start Cloud Cap Technology in Hood River, now an indirect competitor.

Today, Insitu is a leading maker of small tactical unmanned aircraft such as the ScanEagle, a 38-pound long-distance plane jointly developed with Boeing that the military has flown on surveillance missions in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2004. In 2006, Insitu raised $23 million in venture funding from a group led by Silicon Valley-based Battery Ventures that’s helped bankroll its product development and expansion.

From 2003 to 2006, the privately held company saw revenue climb from $2.8 million to $50 million. The uptick has translated into an influx of cash into the area, says Insitu CEO Steve Sliwa. In 2006, Insitu paid Hood Technology, Sage Technology and other local contractors a total of $18 million to $20 million, and had a slightly higher total payroll for its 240 employees, Sliwa says. In early December, it got an additional $25 million in venture capital financing.

“Those are all dollars coming from outside the area. That pumps up the whole community,” he says. That’s likely to continue in the light of a three-year, $18 million contract Insitu and Boeing won from the U.S. Marine Corps in July 2007 for additional ScanEagle support services, a contract with options that could see its total value climb to $381.5 million.

|

Insitu has used part of its newfound wealth to give back to the community. When the city of White Salmon couldn’t afford to repair a 1940s-era former high-school building, Insitu leased half the ailing structure and spent $350,000 renovating it into the company’s software research lab. In the short time Google’s been in The Dalles, the company has started a number of community outreach programs, including providing IT support for local fire and emergency departments.

In addition to bringing high-salaried knowledge workers to the area, tech companies have improved wages for local residents. At the Gorge’s larger tech companies, average annual incomes range from $40,000 to $60,000, and 90% of owners and their employees have health insurance, according to a report on the Gorge tech cluster published in early 2007 by the Gorge Tech Alliance, a local tech business advocacy group.

By comparison, average annual wages in Hood River County are $24,000 and a smaller percentage of workers have health benefits, according to the report. Custom Interface is a case in point. Located just three blocks from Insitu’s downtown Bingen headquarters, Custom Interface is one of the company’s electronic assembly subcontractors. Nancy White, an electronics industry veteran and lifelong Gorge resident, started the business seven years ago and now has 70 employees.

Many of the company’s assemblers previously picked fruit or worked in sawmills or the hospitality business, White says. Now they have above- average wages and medical benefits and are learning skills. And if they work hard and stick around, she’ll pay for their college education. As a result, “I haven’t had a job position open more than 30 days,” White says.

ABOUT THE SAME TIME THE FIRST aeronautics engineers moved to town, other tech types settled in the area, drawn more by outdoor recreation than the business opportunities or amenities. Dave Fenwick remembers them as the bad old days. The former Portland resident sold a software company to Apple and moved to Silicon Valley to work for the computer maker but missed the Northwest and relocated to Hood River in 1992 to start another software venture. At the time, the only empty offices in town were semi-industrial space owned by the Port of Hood River. Getting business phone lines was tough and local insurance agents didn’t know how to classify his software business. “They put us in manufacturing, like we made sheet metal,” Fenwick says.

Gradually, conditions improved. As more tech companies moved in, supporting business and services caught on. The local electric company struck a deal to piggyback fiber-optic data lines on power lines from Bonneville Dam. In 1999, the Oregon Investment Board and a partner agency in Washington state began doling out the first of $5 million in federal development loans and grants to Gorge businesses, including tech companies.

|

Another milestone came in 2004, when a handful of tech executives formed the Gorge Tech Alliance to give local companies a base for networking and joint marketing efforts. With staff contracted from the Mid-Columbia Economic Development District, the Gorge Tech Alliance today holds regular meetings and education sessions and has developed marketing materials promoting the area as a great place for “lifestyle entrepreneurs.” The group is also amassing data on its members, all the better to understand the financial impact they’re having on the area “so we can raise the awareness of officials and the public,” says White, with Custom Interface.

Perhaps the biggest example of the tech sector’s growing significance in the Gorge was Google’s decision to open a 30-acre server farm in The Dalles, taking advantage of cheap electricity, available land, a generous package of tax incentives, and QLife, an existing 18-mile fiber optic loop funded by a consortium of local government agencies.

GORGE TECH COMPANIES FACE some obstacles. There’s too little affordable housing for teachers, firefighters and others who work in service industries that support tech businesses, according to Fashing, the Hood River County economic development manager. Local government and housing authority officials are working to ameliorate that by, among other things, building affordable living spaces on government property, he says.

There’s also been a dearth of commercial property in the area for fast-growing companies that need a combination of office, product development and light assembly space, according to the Gorge Tech Alliance’s 2007 report.

In recent years, ports in The Dalles and Bingen have constructed office buildings on their properties to help solve that problem, and the city and port of Hood River are starting a waterfront district redevelopment project that will include “just the sort of uses we see in our cluster,” says Hood River’s Babitz.

But the biggest obstacle is attracting enough highly educated workers to fill a growing supply of jobs. Because many of those workers come with equally skilled spouses, for every opening “I have to find two jobs,” says Hoag, co-founder and president of Cloud Cap Technology. While prevailing wages in the area are similar to what engineers or software developers make in Portland or Seattle, good schools and easy access to outdoor recreation also are a draw, local business owners say. Once people visit the area they’re hooked. “It’s a culture fit. I bet the original Insitu guys saw it as an impediment, but now it’s a selling point,” Hoag says.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To that end, companies do the usual help-wanted advertising on Internet job boards and at local colleges and university campuses, and then some. The Gorge Tech Alliance held its first job fair this past November, attracting seven hiring companies and 40 job seekers. While the numbers sound small, organizers say they’re pleased with the amount of follow-up interviews scheduled. Insitu’s worked around the workforce problem by maintaining an office in Vancouver, Wash., for employees who can’t or don’t want to sell their homes. The company also changed an in-house policy against spouses working together to attract more married working couples.

Google runs a shuttle bus for eight or 10 employees commuting from Portland, and another for employees from Hood River, arrangements that parallel commuter services Google offers in other cities. It’s “a younger workforce and they want the hustle and bustle of the city,” says Ken Patchett, Google’s site manager in The Dalles. “It’s a good way to mitigate it for both sides, because we get people who are happy at work and live where they want to live.”

When wind-farm makers estimated they’d need up to 400 trained technicians to help build the number of turbines predicted to be erected within a 100-mile radius of the Gorge by 2011, representatives asked Columbia Gorge Community College to create a training program. The first class began in January 2007 and was so successful that some of the 24 students got jobs even before finishing the program, says Susan Wolff, the community college’s chief academic officer.

Graduates are earning $20 to $24 an hour, and one who returned to give a lecture last fall expected to make $125,000 in 2007, Wolff says. Google and a consortium of other local tech companies are talking to the community college about starting a similar training program for IT technicians, Patchett says. “It would be beneficial for the younger generation or people who want to go to school to change their careers and stay employed in this area.”

Wind farms, like the ones hiring those community college-trained technicians, and other alternative energy providers will be the next wave of companies bolstering the Gorge’s tech scene. Among those companies are Seraphim Electric, a solar- and wind-powered electric company that’s already been in the area for five years, and Gorge Analytics, a two-person startup that tests biodiesel fuels. Even Google’s getting into the renewable energy business. In late November, Google said its philanthropic arm would invest tens of millions of dollars in research and development and related investments in renewable energy in 2008 through an initiative called Renewable Energy Cheaper Than Coal, or RE<C. Patchett doesn’t know if those plans include investments in the Gorge, “but I hope so,” he says. “The wind energy business was spawned here. It’s the right environment.”

Alternative energy “is a very big wave for this area,” says Hood River County Commissioner Maui Meyer. “A lot of people want renewable energy. Guess where it comes from? It comes from rural Oregon.”

Michelle V. Rafter is a Portland business and technology journalist who has written for Reuters, The Los Angeles Times and The Industry Standard.

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]

Insitu’s ScanEagle unmanned aircraft launches off a U.S. Navy ship. The planes were developed with Boeing.

Insitu’s ScanEagle unmanned aircraft launches off a U.S. Navy ship. The planes were developed with Boeing.