Real estate versus working timberland: Which will timber companies, and Oregonians, choose?

Real estate versus working timberland: Which will timber companies, and Oregonians, choose?

By Abraham Hyatt

Oregon may have some of the most restrictive land-use laws in the nation when it comes to forestland, but Andrew Miller, president and CEO of Portland-based Stimson Lumber, is willing to make a wager: Sell a 40-acre plot from the 170,000 acres of working forestland that Stimson manages in the state, and then hire a good land-use lawyer.

“You can’t build a Wal-Mart on those 40 acres,” he says. “But I’ll take that bet any day that I could build a home on it in the next few years even though the zoning says it’s not available.”

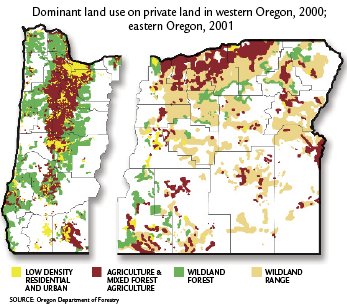

It’s a challenge that has less to do with the strength of the laws governing that land and more to do with what has become perhaps the most powerful issue the timber industry is facing. According to the Department of Forestry, about 10% of the state’s private timberland sits inside urban growth boundaries or development zones. Thanks to demand from the state’s fast-growing population, the land around urban areas suddenly has more value as real estate than as forestland — sometimes three times as much.

“There is a growing economic incentive to fragment land and sell off the pieces,” Miller says. “It’s not healthy in an economic sense or for the ecology or the environment but it’s driving people [in the industry] to look for value outside of selling trees.”

Is that working forestland worth more to the public as much-cherished woodlands or as something else? And if it’s forest, who will pay to keep it that way if it’s worth more as real estate?

The Department of Forestry, industry groups and foresters are looking at different solutions, including conservation easements and tax incentives. U.S. Senators Gordon Smith and Ron Wyden and others are looking at different ways to increase the amount of timber harvested on federal lands, which would help buoy the industry as a whole.

But it will be Oregonians who will play the biggest part in finding an answer. The recent past holds two examples of voters trying to balance land-use expectations against the value of development: Measure 37, which compensated property owners for development rights lost because of land-use laws; and Measure 49, which cut back on the amount of development allowed by Measure 37, specifically on farm and forest lands. Whether it’s funding conservation easements or ballot measures, in the coming decades the public is going to have the strongest voice in determining how Oregon’s private forests are managed.

This is a new challenge, one that’s pitting forestland against new economic forces, says Matt Donegan, co-president of Forest Capital Partners, a timberland investment group based in Portland and Boston. “Hoping is not a strategy and I don’t think we can hope anything is going to go away. We’re going to have to have to start evolving if we want to preserve our working forests.”

This is a new challenge, one that’s pitting forestland against new economic forces, says Matt Donegan, co-president of Forest Capital Partners, a timberland investment group based in Portland and Boston. “Hoping is not a strategy and I don’t think we can hope anything is going to go away. We’re going to have to have to start evolving if we want to preserve our working forests.”

THE INDUSTRY’S CONCERNS these days go beyond the value of forestland. The ongoing drop in homebuilding, the first of this size since the 1980s, means Oregon mills are operating at a loss, says Jim Geisinger, executive vice president of Associated Oregon Loggers. He predicts big cutbacks in production over the first half of this year.

Jim Geisinger, executive vice president of Associated Oregon Loggers, predicts big cutbacks in production this year for Oregon mills thanks to the ongoing drop in homebuilding. Jim Geisinger, executive vice president of Associated Oregon Loggers, predicts big cutbacks in production this year for Oregon mills thanks to the ongoing drop in homebuilding.PHOTO BY JON MEYERS |

Dale Riddle is senior vice president of legal affairs at Eugene-based Seneca Jones Timber, which manages about 166,000 acres of forestland in western Oregon. He argues the two biggest challenges are the trade relationship with Canada, which subsidizes its timber industry, and the restrictive U.S. federal timber policy.

In the 1980s timber from federal lands made up 50% to almost 60% of Oregon’s annual harvest. Since then the federal government has cut back logging following legal battles over endangered species habitat and management practices; timber from federal lands now makes up less than 10% of the state’s annual harvest. That puts most of the state’s timber production on private lands and creates a fire risk on overgrown federal lands.

Other pressures on the industry are more indirect: Over the past five years, Plum Creek Timber Company, Longview Fibre, Rayonier, and Potlatch, all of which own land either in Oregon or the Pacific Northwest, have transitioned from traditional corporations to real estate investment trusts — a special tax status for companies whose focus is income-producing real estate assets. (Weyerhaeuser is the only major company to not make the switch.) These companies aren’t necessarily abandoning the timber business. Analysts say timber performs well even when the stock market does not.

But when the land is worth more than the timber, REITS sell. After becoming a REIT in 2006, Potlatch killed plans to build an $8.1 million poplar mill in Boardman. It announced it would sell 300,000 acres of its timberland in Idaho — where it’s the largest private landholder — and three other states over the next decade.

Plum Creek, the nation’s largest private landholder, has run up against controversy for its use of its timberland. In Washington, Maine and Montana, Plum Creek has sold land to developers or is actively developing resorts and housing developments on 100,000-plus acre parcels of its own timberland. Most famously, the company — which did not respond to requests for an interview for this story — also filed, and then withdrew, Oregon’s largest Measure 37 claim. The claim would have given Plum Creek the ability to develop 32,000 acres of the 372,000 acres of forestland it owns in the state.

That kind of land sales or development by REITs could have an impact on the state’s smaller, privately held timber companies, especially if those big companies are harvesting timber or selling land based on stockholder demands rather than on a long-term plans. As Geisinger points out, “When you’ve got an accountant managing forests, that’s not always the best forestry.”

Cascade Timber Consulting, which is based in Sweet Home, manages 145,000 acres of forest in Linn County. Its president, Dave Furtwangler, points to another potential long-term concern: If real estate trusts push for short-term returns on their land, it could drive up the cost of all timberland and price out smaller owners.

The biggest impact of real estate-based management practices could be in how they push people and working timberland into tighter and tighter spaces, says Bob Ragon, executive director of Douglas Timber Operators in Roseburg. “If they subdivide for ranches and build lodges out here, that brings in a whole different question: How do we manage our lands when we have houses sitting right next door?”

ACROSS THE COUNTRY, there are a lot of new houses sitting on what used to be working timberland. In the past 15 years, more than 30 million acres of private working forest in the U.S. changed hands. Oregon — where 35% of forestland is privately owned — is following that same trend toward fragmentation where large timberland sales are followed by smaller and smaller sales, according to the Department of Forestry,

If big timber companies push for real estate-based returns on their land, Cascade Timber Consulting president Dave Furtwangler thinks it could drive up the cost of all timberland and price out smaller owners. PHOTO BY JON MEYERS |

The value of that land is multifold: jobs, rural economies, supporting industries, habitat, biodiversity, water, carbon sequestration (the natural process of trees removing and storing carbon dioxide, which plays a major role in global warming, from the atmosphere). But to save that land, the timber industry can’t be the only advocate, Donegan says.

“It’s got to be the conservation community who identifies the value of working forests,” he says. “Conservationists need to stand up as a third party and say, ‘This is a crisis.’”

Some of them are. Bob Stacey, president of arguably the state’s most influential conservation group, 1,000 Friends of Oregon, has a clear stance on working forests: “We’re going to continue to need forest products. And we’re going to continue to have some of the best land in the world for growing high-quality timber.”

Stacey says something needs to happen to make sure responsible forest management is economically viable. One solution he and others are looking at is conservation easements. An easement is the selling of specific rights, such as development or grazing, to a conservation organization. The landowner keeps ownership of the property but gives up whatever right was sold. While common in California, Idaho and other states, they’re rare in Oregon because of their redundancy with some of the state’s land-use laws.

They could be useful here for one major reason. Timber companies would get compensated for not splitting up their land into small parcels and selling them, which they’re allowed to do under current laws.

Unsurprisingly, buying development rights isn’t cheap. The Trust for Public Lands spent $9.5 million for conservation easements on 55,000 acres owned by Potlatch in Idaho. Donegan and Stacey point to a few federal and state programs that offer funding for easements. Additionally, easements wouldn’t need to be — nor could they realistically be — purchased for all timberland, only the most valuable and prone to sale. One example of that is an easement the Trust for Public Lands bought for 1,500 acres of timberland near Salem this last October.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

UNTIL THE PAST FEW decades, the intersection of logging and residential growth has had little impact on the timber industry. Conservation efforts from outside the industry played a minor role as well. The biggest force that shaped the industry was federal forests.

As demand for timber spiked during World War II, the U.S. Forest Service agency began its commercial timber sales program. In 1945, Oregon produced 6,050 million board feet of timber, 720 million of which came from federal land. Ten years later the state’s overall total had jumped to 9,720 million board feet thanks in large part to a 145% increase in the amount of timber from federal forests. That was the heyday that would set financial and employment expectations for years to come.

Then came the spotted owl, federal lawsuits from environmental activists concerned with management policies, and new regulations. In 1994, four years after the owl was listed as an endangered species, the Forest Service cut timber production on federal lands in Oregon by 50%. The state’s total production, which Oregon State University researchers had already identified as being on a downward trend, dropped 20% from the year before. The number of logging jobs alone plummeted 30% over the course of that decade.

It’s no surprise that any effort to bolster the timber industry begins with an attempt to reopen federal lands. And the efforts — from tiny towns to Washington, D.C. — to do so could fill a book. Success has been slow.

Since 2000, timber harvests on federal lands in Oregon have climbed from 330 million feet a year to about 600 million last year. Part of that growth is an attempt by the Bush Administration to meet the requirements of the Northwest Forest Plan — the 1994 plan that restricts logging in spotted owl habitat but sets aside a dedicated source of harvestable wood. Last year the federal Bureau of Land Management began working on a plan that would further increase logging on land protected by the plan. If implemented it would likely face opposition from at least some environmental groups.

A team from conservation, industry, academic and state groups laid out a possible federal forest restoration plan at this year’s summit on the Oregon Business Plan, where Smith and Wyden also pushed for more harvesting, respectively focusing on larger harvesting amounts and thinning efforts. But their goals were the same: improving the economic and environmental impact on the industry and the state.

A CHANGING WOOD-PRODUCTS market, a growing population with bigger personal incomes, a new demand for real estate in rural areas: Add it up and you get a changing value for forestland. The future of timber is not necessarily in timber.

“The environmental community has been beating up on us for years. They thought we had no options and were committed to growing [trees] no matter how costly. But what we know and what they’re discovering is that we do have options,” Miller says.

The benefits of working timberland cited by the industry and conservation groups are clear: carbon sequestration, water quality, habitat, controlled sprawl, jobs. Combined, the forestry and wood products industries are one of the largest employers in Oregon, providing about 61,000 jobs — 12,000 specifically in forestry and logging — and a $2.5 billion payroll in 2005.

The industry, by its own admission, has failed at educating Oregonians that working timberland is good for more than just the companies that own them. And convincing the public to place a monetary value on something unseen, like the potential for development, will be difficult. Just ask a few of the backers of Measure 37: Seneca Jones Timber, Cascade Timber Consulting, Stimson Lumber. This new attempt could be even harder.

But advocates for working forestland have a strong argument: The effects of a fire or a clear-cut are transitory compared to the permanence of development.

“We need to make people understand that it’s in their interest to keep land in forest production,” says Ray Wilkinson, legislative director for Oregon Forest Industries Council.

“They might not like what the timber industry does all the time, but they’ll like the alternative a lot less.”

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]