BY JOSHUA HUNT

BY JOSHUA HUNT

Will rural Oregon cash in on legal marijuana?

BY JOSHUA HUNT

BY JOSHUA HUNT

PHOTOS BY CHRIS NOBLE

Dan is 41 and has spent the last 18 years of his life working for a major aircraft company in the Portland area. It’s a good living but nothing compared to the millions of dollars worth of pot that he sells each year — legally.

Far from the image of Walter White, the suburban drug kingpin of television’s Breaking Bad, Dan, who asked that we not print his last name, is just one of hundreds of entrepreneurs who are betting big on medical marijuana in Oregon. It’s far from a long shot, according to a report cited by the Huffington Post, which predicts legal marijuana sales will grow to $2.34 billion nationally in 2014. If the report is correct, legal pot will outstrip even the competitive smartphone market in terms of growth this year.

That growth has been sparked by a national trend unfolding in states that have moved to decriminalize marijuana, which is still illegal under federal law. In Colorado, a family-owned shop that began in 2010 as a medical marijuana dispensary took in nearly $100,000 on the first day of business operating under new state laws that allow the sale of recreational pot, according to Yahoo News.

In Oregon, pot has also been paying off for businessmen like Dan, an early adopter who opened Mt. Hood Wellness Center, a medical marijuana dispensary with two Portland area locations, three years ago.

Business is booming, thanks to more than 60,000 registered Oregon Medical Marijuana Program cardholders, whom researchers at Oregon State University estimate spend about $96 million annually on cannabis products. But that number is set to explode in 2014, with more people than ever before eligible for medical marijuana under a broader set of qualifying conditions that now includes post-traumatic stress disorder. Less than a month after patients diagnosed with PTSD legally qualified for OMMP cards, many dispensary owners had already noted an increase in business from them — many of them veterans.

There is, however, another reason industry insiders are expecting a boost in 2014. In March the Oregon Health Authority began its medical marijuana dispensary registry program, which gives operations like Dan’s a new set of rules to follow: mandatory, round-the-clock security; required laboratory testing to ensure marijuana that is free of mold, mildew and pesticides; rules keeping dispensaries more than 1,000 feet away from schools and other dispensaries.

It’s a system industry experts say is going to separate the weed from the chaff, allowing legitimate businesses to generate millions in annual revenue and attracting mainstream investors, while forcing out a criminal element that have thrived on the fringes of Oregon’s medical marijuana industry.

“This registry is going to bring transparency into the equation, and that’s going to make the whole industry more honest, open and profitable,” Dan says. “For the first time, businesses like mine will be able to advertise, and with all dispensaries required to test their product, patients aren’t going to get cheated by criminals looking to make a quick buck selling bad weed to people who don’t know any better.”

Momentum to legalize marijuana continues to grow, and the registry will give the industry a level of legitimacy it has never known before. But in Oregon, considered a seminal state in the debate over legalizing pot, there are also signs the industry will evolve along familiar lines — reinforcing an urban/rural divide that has marked the state’s history for decades.

As of March 7, 281 dispensaries had applied to register with the state, the majority in Multnomah County. In Portland neighborhoods like Irvington and Hawthorne, nondescript dispensary storefronts are often distinguishable only by their most conspicuous marking: a green cross that owes all but its color to the Red Cross logo. From the outside, they look like veterinary clinics. From the inside, many resemble a dentist’s office.

As of March 7, 281 dispensaries had applied to register with the state, the majority in Multnomah County. In Portland neighborhoods like Irvington and Hawthorne, nondescript dispensary storefronts are often distinguishable only by their most conspicuous marking: a green cross that owes all but its color to the Red Cross logo. From the outside, they look like veterinary clinics. From the inside, many resemble a dentist’s office.

The sheer number of dispensaries cropping up in Portland hints at the entrepreneurial chord that has been struck by the state regulations. But the atmosphere in rural Oregon is distinctly different.

Consider J’s Green House, a medical marijuana dispensary in Roseburg. There is no green cross, and no mistaking it for a veterinary clinic or dentist’s office. Instead, crossing a set of train tracks that run parallel to the highway leads to an empty lot, the final resting place of 10 small, moldering boats. In the distance sits a pair of large unmarked hangars.

Its anonymity is hardly surprising, considering the city of Roseburg has never approved a business license for J’s Green House or any other medical marijuana dispensary, according to Koree Tate, an assistant at the Office of the City Manager.

Another unlicensed Roseburg dispensary is operated by “Mary,” a middle-aged woman who works alone, helping people manage their pain the way she once helped her husband, after he was diagnosed with cancer some years ago. “I know we’re listed as a dispensary online, but we really aren’t a dispensary,” she says. “I just help connect patients with growers who can get them what they need. I’m only a middleman.”

What Mary is in the middle of is the legal business of providing marijuana to OMMP cardholders and the illegal business of cultivating marijuana plants. Oregon is the fourth-largest indoor-cannabis-producing state, and the 10th-largest cannabis-producing state overall. But paradoxically, much of the potent crop that the state is famous for producing ends up in out-of-state illicit markets rather than in legal dispensaries. It is equally ironic that the legitimization of the marijuana business has yet to yield positive returns in places like Roseburg, which sits at the northern edge of the banana belt, where the agreeable climate and soil nurture many of the state’s more than 100 outdoor-cannabis farms.

This is because cannabis is still considered a Schedule 1 drug under federal law, which doesn’t differentiate between crops destined for legal or illegal markets. In the eyes of the federal government, it’s all the same, so doing business out in the open is risky. James Bowman, owner of Jackson County’s High Hopes Farm, found this out the hard way in late 2012, when agents from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency raided his operation. According to The Oregonian, Bowman’s farm was set to deliver medical marijuana to more patients than any other single source in the state.

Growers can also run afoul of federal tax laws, since, under federal law, only the cost of materials can be accounted for. In other words, the labor costs associated with growing marijuana are illegal, even for those growing plants on behalf of registered OMMP cardholders. This often leads farmers, like Bowman, to pay field hands in product, further drawing the ire of authorities.

These problems will be alleviated under the registry system, which will allow, for the first time, the honest accounting of labor in growing medical marijuana, according to dispensary operators. Operators will be required to keep detailed records, which the state will check during a regular annual inspection. Dispensary owners will also trade the watchful eye of the Oregon State Drug Enforcement Agency for two state inspectors assigned to the registry program.

But Southern Oregon’s pot farms face other threats — competition from rapidly expanding indoor-grow operations in cities like Portland and Eugene.

The RoseBud Wellness Center blends comfortably into the scenery in Portland’s hip Irvington neighborhood. Its interior is bright and sterile, with good natural light and not even a trace of illicit odors in the air. All around are the signs of a shop that is in compliance with registry rules ahead of schedule, right down to security cameras and a secure area for storing the shop’s stash of medical marijuana. Behind the counter, T-shirts emblazoned with the RoseBud logo hang above a refrigerator stocked with bottled water.

The RoseBud Wellness Center blends comfortably into the scenery in Portland’s hip Irvington neighborhood. Its interior is bright and sterile, with good natural light and not even a trace of illicit odors in the air. All around are the signs of a shop that is in compliance with registry rules ahead of schedule, right down to security cameras and a secure area for storing the shop’s stash of medical marijuana. Behind the counter, T-shirts emblazoned with the RoseBud logo hang above a refrigerator stocked with bottled water.

“We’re a boutique shop, and we specialize in a range of high-end, laboratory-tested cannabis products,” says Sean Wilson, the shop’s co-owner and manager. “We opened three months ago, and so far we’ve had about 600 unique patients walk through our door.”

The marijuana Wilson is selling to those customers isn’t coming from Oregon’s banana belt but from laboratories and sophisticated urban indoor-growing operations. Among the most popular strains they sell is the notoriously powerful “Girl Scout Cookie,” which costs upwards of $3,000 per pound.

The dozens of strains sold at RoseBud have all been tested, and Wilson can tell customers what kind of high they are going to experience even before they lay their money down. Because the new registry rules require all of Oregon’s medical marijuana to be laboratory tested, designer strains and customizable highs are going to be in demand — and at premium prices.

This is exactly the kind of niche, upper-tier market Wilson wants to cultivate. His business plan revolves around providing customers with detailed information on the THC and CBD content of the cannabis they buy. High levels of THC, he says, produce the high commonly associated with marijuana use, while high levels of CBD produce a different medicinal effect. “The CBD actually treats the pain, while the THC distracts you from the pain,” says Wilson. “In addition to being required under the new regulations, testing helps people get what they need to manage their condition.”

Just down the street from Wilson’s shop is Rose City Laboratories, one of the places local dispensaries can bring their product to have it tested and certified. It’s just one example of the cottage industry that is springing up around the new dispensary registry and may prove to be the most profitable area of investment. One lab owner said that he expected to pull in upwards of $12 million in revenue annually once the new regulations go into effect.

The labs are also where so-called “medibles” — edible marijuana products — can be tested to determine how the cooking process has affected THC content. Medibles, according to Wilson, account for about one-third of all the medical marijuana sold to patients at RoseBud Wellness Center. Companies like Auntie Dolores specialize in preparing and marketing these cannabis-laced foods, which include products like chocolate-fudge cake, brownies, chili-lime peanuts, savory pretzels and caramel corn.

It all fits what Wilson calls the “boutique” nature of Portland’s dispensary scene, with its abundance of niche markets stimulating job creation and entrepreneurship and where applications for business licenses related to the industry are on the rise, according to a city clerk. In rural Oregon communities, by contrast, “there have been a lot of efforts to stop the registry, and to prevent dispensaries from opening up shop,” says Karynn Fish, a public information officer with the Oregon Health Authority.

In March the Oregon Senate approved giving local governments authority to keep out the dispensaries until May 2015. So far, 21 cities have moratoriums in place against pot dispensaries, including the city of Medford, Josephine County and Polk County. These political victories could cost communities like Roseburg, where the unemployment rate stands at 9.7% — nearly two points above the state average. Rural counties also miss out on local taxes and fees. Dispensary owners pay the state a $4,000 application fee, and $500 of that is nonrefundable, regardless of whether or not the application is approved.

Dispensaries, labs and businesses that produce medibles also produce jobs and pay taxes — even if industry experts expect the economic benefit will not be as dramatic as in states like California, where the dispensary business is also subject to the state’s 5.6% sales tax. Indeed, some experts believe legalization efforts around the country will be propelled by states’ need for tax revenue. In Colorado legalization is expected to generate $134 million in tax revenue for the upcoming fiscal year; already in January 2014, the first month retail sales of marijuana went into effect, Colorado netted $3.5 million.

Oregon’s legal pot industry will unfold along a traditional urban-rural divide, with much of the initial growth blossoming along the I-5 corridor cities, agrees Roy Kaufmann, president of the Kaufmann Group, a marketing and public affairs consultancy working to “rebrand” the cannabis industry. But Kaufmann also believes rural counties, already proud of their indigenous wine and brewery operations, will eventually warm to a regulated industry that helps fill depleted government coffers.

At this stage, exurban counties are the big unknown, Kaufmann says. “People are watching Washington County, Clackamas County,” he says. “Will they follow the lead of Multnomah County? Or are they going to follow the lead of the rural counties — Polk, Marion — that have voted against legalization?”

|

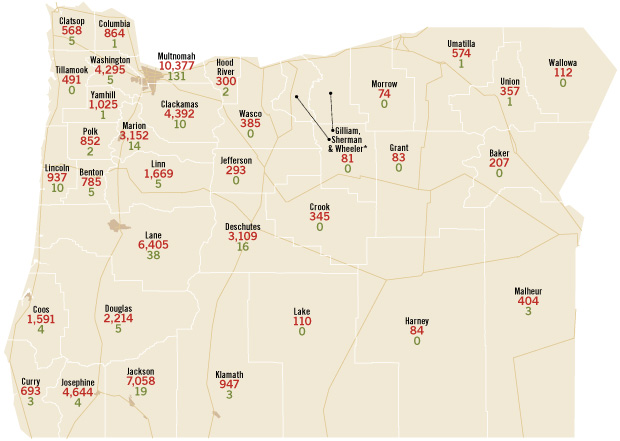

| Medical Marijuana in Oregon Registered patients (shown in red) and dispensary applications (in green) by county SOURCE: OMMP. Figures as of March 24, 2014 |

As Oregon cities alternately embrace and reject the economic potential of the burgeoning cannabis industry, mainstream investors are moving full-steam ahead. Last summer, Seattle’s Privateer Holdings became the cannabis industry’s first private equity firm when it announced the completion of its Series A funding round, which raised an initial $7 million from investors. Privateer CEO Brendan Kennedy previously served as COO of a Silicon Valley bank that funded tech startups, and he founded Privateer in 2010 with Yale classmate Michael Blue.

“Privateer is focused on elevating the conversation and building trusted, approachable brands in the cannabis space,” Kennedy said in a press statement. “We are moving the cannabis industry out of the shadows and into the light.”

They aren’t the only ones. Advanced Cannabis Solutions, whose stock rose 447% by late January, obtained access to $30 million in credit that it will use to acquire properties to lease to marijuana growers, according to Bloomberg.

National players are paying attention to the changes coming to Oregon’s medical marijuana market. In February Portland hosted the Northwest CannaBusiness Symposium, an industry event planned by the National Cannabis Industry Association. The event featured talks on cultivation and retail operations, marketing, and a government relations panel talk with Congressman Earl Blumenauer.

Respectable cannabis investors aren’t the only sign of changing times. In January Federal Drug Enforcement Agency Chief of Operations James L. Capra told members of Congress that he considers legalization of marijuana to be “reckless and irresponsible.” But at least one former Oregon-based DEA agent doesn’t seem to share those views. Just one week after his former boss blasted the legal pot industry, former agent Patrick Moen announced that he’d be taking a job with Seattle’s Privateer Holdings.

In 2014, there are plenty of uncertainties surrounding Oregon’s marijuana market — after all, the federal government still considers pot an illegal drug. In late March the Oregon Health Authority also proposed rules banning “medibles:” the concern is children will be attracted to hash brownies and other treats. Still, in California and Colorado, laws legitimizing the sale of marijuana have led to increased entrepreneurship and job creation, exploding profits and tax generation for these states.

As Oregon moves the cannabis industry off of the black market, the potential exists to shift the profits generated by this cash crop into the mainstream state economy. But questions remain about just how much rural Oregonians will reap from legalization. Says Kaufmann: “It’s incumbent now on the regulated medical cannabis industry to prove they can be the kinds of business community neighbors that any town in Oregon would want to have.”