Renters and owners find costs take more of their income.

Renters and owners find costs take more of their income.

By Brandon Sawyer

|

|

|

|

|

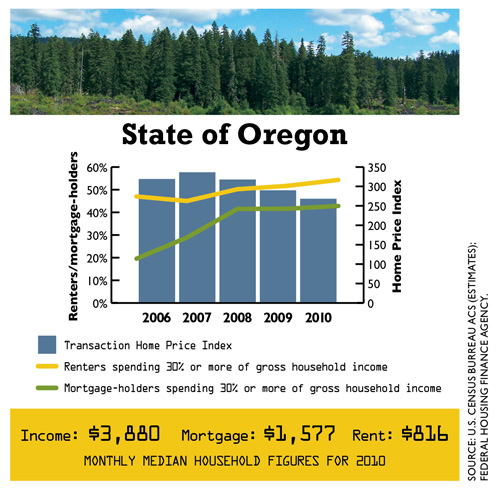

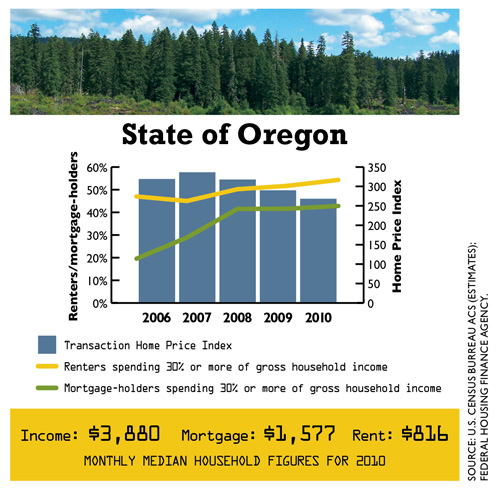

Oregon arrived a little late to the housing crash and didn’t fall quite as hard as states like Florida and Arizona. But as real estate in some states begins to recover, prices here have continued to fall. Homes have lost about a quarter of their median value since their peak in 2007.

Meanwhile, household incomes are still reeling in the wake of the recession, pummeled by higher-than-average unemployment and wage stagnation. So even though home prices continue to fall, more Oregon homeowners and renters are spending in excess of one-third of their income on housing.

Housing costs that take more than 30% of a household’s income are considered unaffordable. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) uses 30% to figure low-income housing subsidies; lenders use it to determine mortgage qualification. Households paying more are deemed “burdened.”

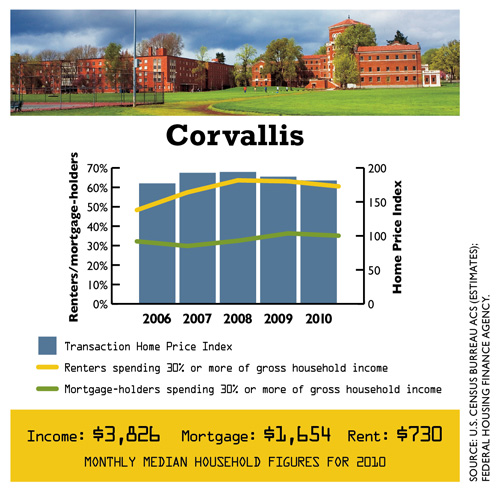

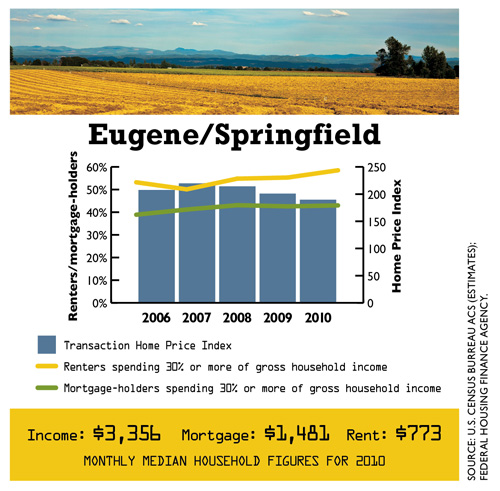

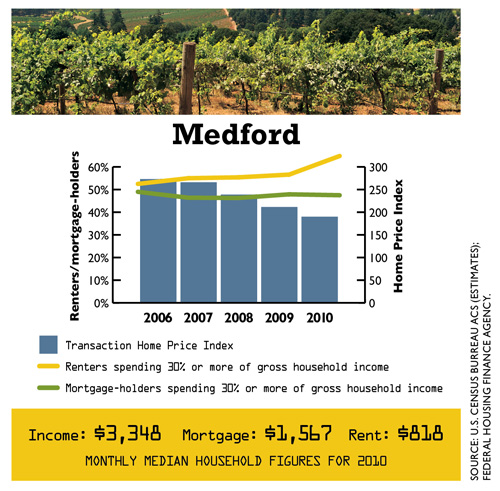

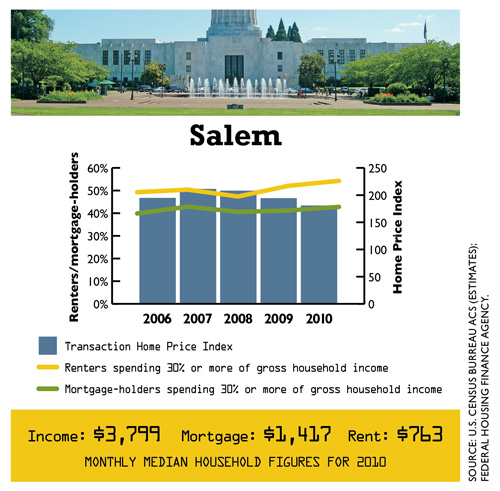

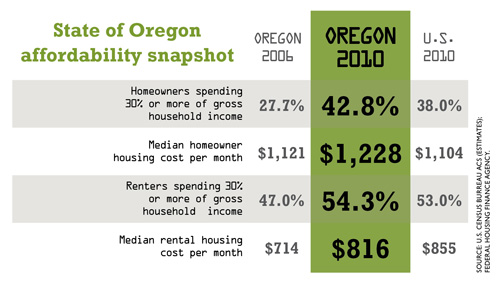

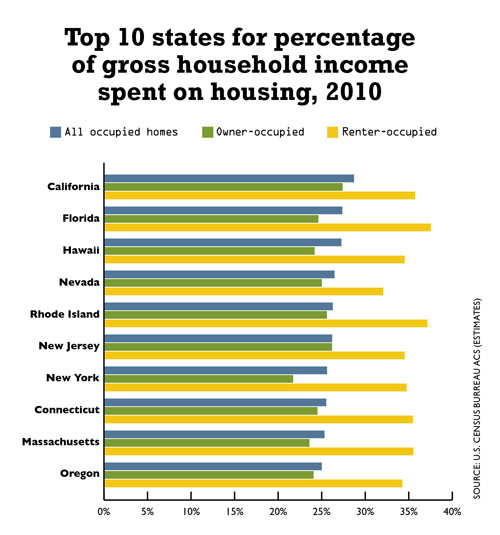

In 2010 Census estimates indicate that 54.3% of Oregon renters were burdened, increasing 7% from 2006, while 42.8% of mortgage holders were burdened, a jump of 15% in five years.

One factor in expensive rentals is the state’s low inventory. The statewide rental vacancy rate in 2010 was 5.6%, the fourth tightest in the country.

Oregon’s homeownership is among the lowest in the nation and has fallen further since the recession. In addition, of all occupied homes in 2010, 37% were rented, the seventh-highest rate in the nation.

“There’s a lot of pressure on rental rates, and that’s probably because more people who had been in homeownership are now looking in the rental market,” says Margaret Van Vliet, director of Oregon Housing & Community Services, the statewide agency that administers federal money and tax credits for low-income housing. “There’s been hardly any construction of new multifamily [housing] for many years,” she adds. “The market is re-correcting but, in the meantime you’ve got folks who are really kind of stuck. So it’s a tough time across the whole spectrum of housing needs.”

|

|

|

|

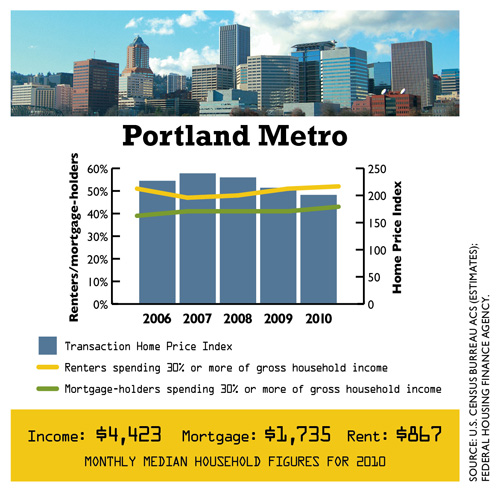

According to a report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition, Out of Reach 2012, America’s Forgotten Housing Crisis, a full-time worker in Oregon needs a “housing wage” of $13.01 per hour in order to afford to rent a one-bedroom apartment at fair market rent (calculated by HUD at 40th percentile market rents). The average wage in Oregon of a full-time worker is $12.59 per hour. The biggest affordability gap in the state is in Columbia County where the average wage is $8.26 and the housing wage is $14.83. Portland has a small affordability gap because it has more multifamily housing and better-paying jobs; its housing wage also is $14.83 and its average wage is $14.33.

Van Vliet says persistent unemployment and underemployment have been most responsible for the inability of Oregonians to afford rents, as well as contributing to foreclosures. Hiring is slowly improving, though most of the new jobs are in the Portland metro area “so the recovery is going to be lopsided, and that’s going to put rural communities further behind,” she says. The five counties still suffering seasonally adjusted unemployment in excess of 12% in February were all rural: Crook, Grant, Harney, Jefferson and Lake. The statewide rate was 8.8%.

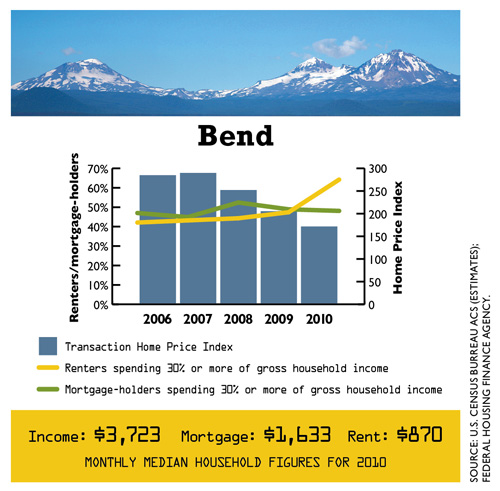

Within the state’s urban areas, Bend and Medford stand out as the least affordable housing markets, though both may be improving. In 2010, 48% of mortgage holders and more than 64% of renters in the two fast-growing metros were housing burdened. Since 2006 the burden hadn’t changed for homeowners, but renters’ burdens grew 22% in Bend and 12% in Medford. Meanwhile, the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s All-Transactions Home Price Index, an indicator of single-family home prices and refinance appraisals, dropped 40% for Bend and 30% for Medford.

Bend also witnessed the most dramatic surge of another indicator of unaffordable homes: foreclosures. In Deschutes County, notices of homeowner default shot up from 45 in 2007 to 314 in 2010. John Helmick, CEO of Eugene-based Gorilla Capital, which buys, remodels and resells foreclosed homes, says that after peaking in 2010, this indicator is finally brightening in 2011: “Throughout all the 20 Oregon counties in which we track the data, we saw an average of 25% decline in the number of new foreclosures being filed, and we see that same decline continuing in 2012.”

Jaynee Beck, a realtor with Duke Warner Realty in Bend and president of the Central Oregon Association of Realtors, also has reason for cautious optimism on the ability of new buyers to afford a home. “Our market has really done a big correction,” she says, “and it’s brought a lot of the buyers back to our market that were priced out of it in the boom.” That includes many locals who grew up and worked in Bend but had to commute 45 minutes away to find affordable housing when the minimum price in Bend was about $300,00.

“Now we actually have homes under $100,000,” says Beck, “so those people can come back to Bend.

Brandon Sawyer is research editor for Oregon Business. He can be reached at [email protected].