Manufacturing makes up more of the state’s GDP than almost any other state, and jobs in the sector are projected to grow.

Manufacturing makes up more of the state’s GDP than almost any other state, and jobs in the sector are projected to grow.

{artsexylightbox}{/artsexylightbox}

BY BRANDON SAWYER

Click on any graph to view larger. |

|

|

|

|

|

From two-by-fours to semiconductors to frozen peas, Oregon has a storied history of making things to export out of state, bringing in much needed revenue and employing generations of Oregonians in family-wage jobs. But since the crash of timber industries in the 1980s and years of off-shoring mania by U.S. companies, the media has long reported that manufacturing is dying.

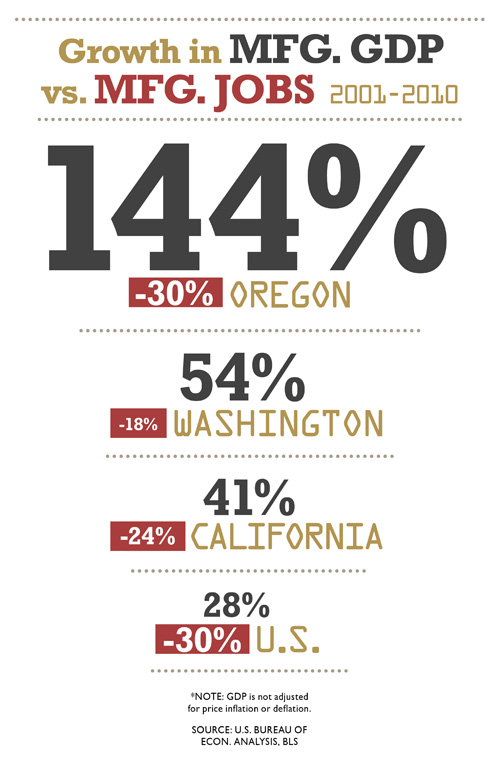

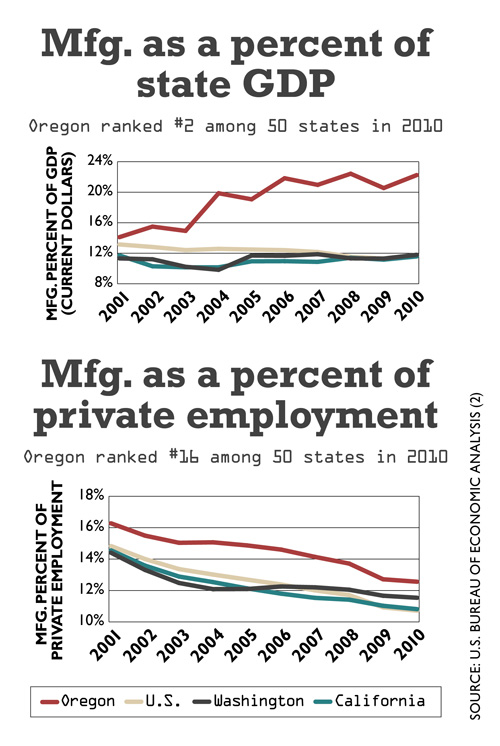

Reports of its death, however, are greatly exaggerated. Today, diverse industries are building on the state’s manufacturing legacy, taking advantage of cheap power, pristine water, rich natural resources and easy access to the Pacific Rim. In 2010, manufacturing’s 22% share of gross domestic product (GDP) made Oregon No. 2, behind Indiana, a jump from No. 18 in 2001. Looking ahead as global dynamics shift, the state could be poised for “on-shoring,” a return of manufacturing from abroad. By 2020, manufacturing jobs are projected to grow 15% in Oregon, as they decline 0.6% nationwide.

The picture isn’t all rosy. While health care and other service jobs expanded over the past 20 years, manufacturers have automated operations and increased efficiency. As a result, manufacturing represents a diminishing share of Oregon’s labor force, from 20% in 1990 to less than 13% in 2010.

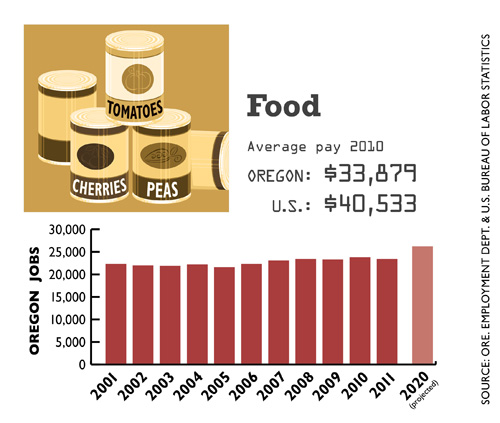

Nevertheless, following the Great Recession, employment in a number of durable goods industries has bounced back, and the state actually added food and beverage jobs through the recession.

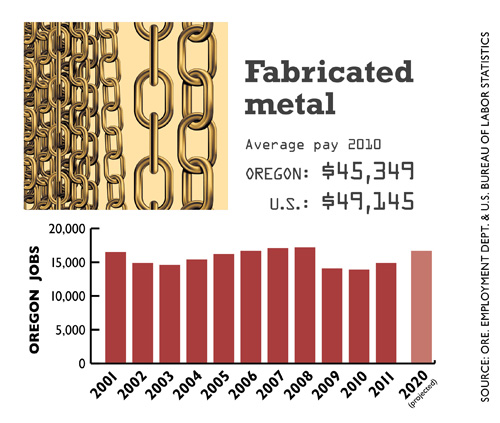

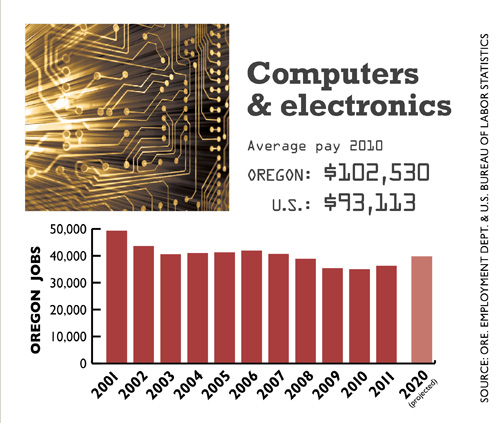

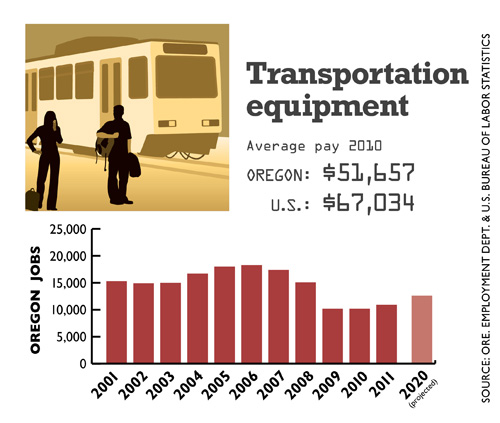

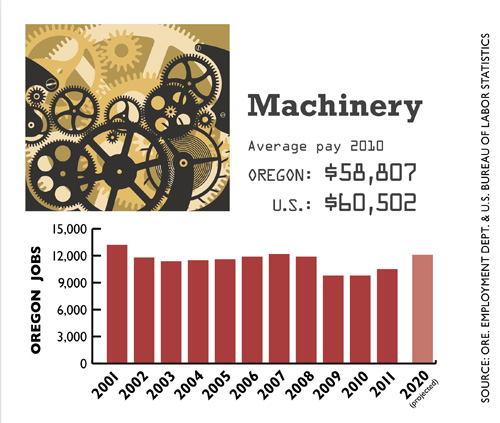

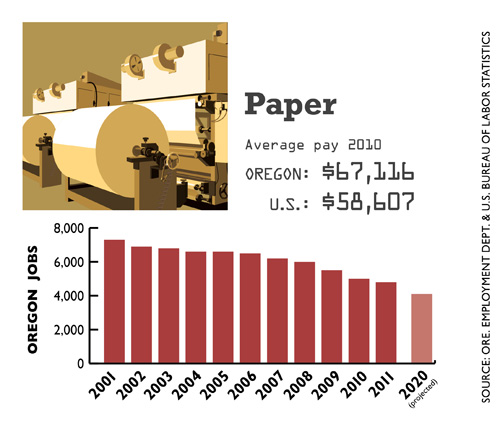

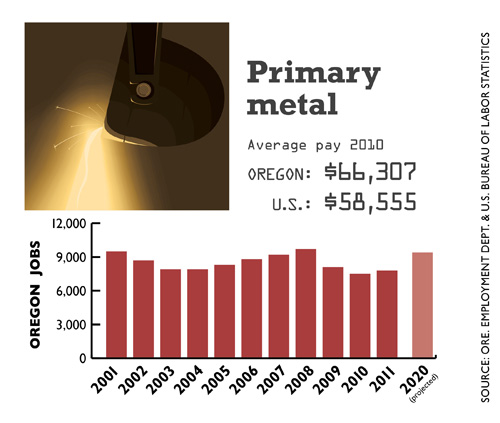

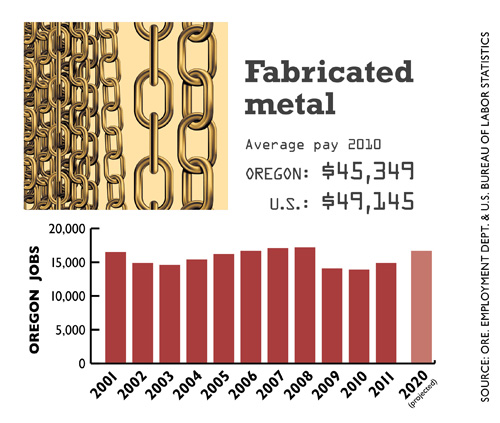

A surge in exports, especially high-tech and metal products, is driving that growth. Computer and electronic products comprised 79% of Oregon’s durable goods GDP in 2009, up from 50% in 1999. The sector added 3.7% more jobs in 2011, surpassing 36,000, by far the largest and best-paid group of manufacturing workers in the state. The Employment Department projects 14% more of these jobs this decade. Likewise, fabricated metal products, machinery and transportation equipment grew 7% and primary metals grew 4%. All are projected to grow more than 20% by 2020.

“[These] are good examples of Oregon manufacturing that can take advantage of exporting,” says Nick Beleiciks, an economist with the Oregon Employment Department. “They’re competing on a national and global scale.”

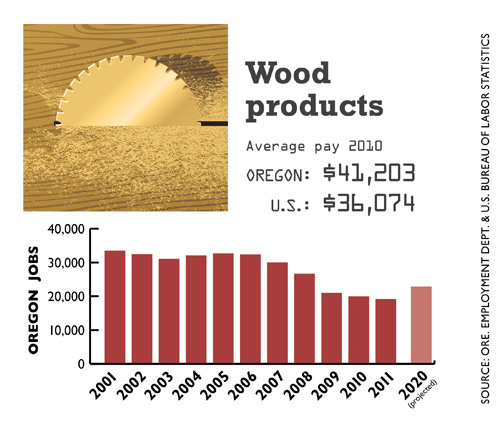

Even wood products manufacturing, as it crawls out of the real estate crater, is expected to add 14% more jobs by the end of the decade after losing 40% between 2001 and 2010. In doing so, it lost its place as second-largest manufacturing employer to food manufacturing, which grew jobs a remarkable 7.3% in the last decade.

Despite the rebound, jobs in manufacturing are still endangered. For example, computer and electronics employed nearly 50,000 in 2001, about 14,000 more than it does today. “This industry took big advantage of off-shoring,” says Beleiciks. With final assembly overseas there was “a huge impact on the number of people working so what they’re doing [here] now is really the high-end stuff.”

Technological improvements in food processing also impact jobs, as employers “can make more food with less people,” Beleiciks says.

{artsexylightbox}{/artsexylightbox}

Click on any graph to view larger. |

|

|

|

|

|

In light of these obstacles, how can Oregon maintain its upward trajectory? Paradoxically, job-killing automation may reduce the need for off-shoring, says Beleiciks. “As labor becomes a smaller portion of the output then it makes for less of a need to go after cheaper labor by off-shoring. There has been a lot of talk recently about on-shoring.”

Two case studies spotlight this phenomenon — as well as a growing emphasis on workforce training to keep local manufacturers competitive. In 2010, Portland-based KEEN Footwear opened a footwear factory in the Rose City. CEO James Curleigh — who has been in Oregon’s spotlight after meeting with President Obama in January –— cites three reasons: First, duty and transportation rates; labor and material costs in Asia have escalated, so “the economics of building in America start to make a lot more sense.” Second, digital-age “supply chain acceleration” has prompted the company to want tighter control over capacity, sourcing and quality standards. And third, KEEN used the factory to launch the higher-priced Utility line of steel-toed boots for American workers, which incorporated innovations they wanted to protect. Initially, the factory employed about 15 workers, but since then, as Utility became KEEN’s fastest growing brand, employment has doubled and Curleigh expects to hire more.

Earth2o, bottler of natural spring water in Culver, is another growing Oregon manufacturer. Last summer, demand was so strong for its product that it had to pull back from sales in Japan and reinvest to expand capacity, says CEO Steve Emery. And now it’s opened sales in China. Emery has seen “an expansion of marketplace” for Oregon products. “My friends in the beverage or the food industries all have been expanding their geography whether it’s outside the region or outside the country.”

One way Earth2o made its product stand out was by training its workforce in the highest level of NSF Safe Quality Food certification. Earth2o isn’t alone in using workforce training to raise its profile. Agnes Balassa, a workforce policy adviser to the governor, points to groups of small manufacturers that have banded together in consortia in recent years for high-performance trainings such as lean manufacturing, which not only reduces waste and spurs efficiency, she says, but also trains “a workforce to be more focused on problem-solving, quality management, being actively engaged with the work.”

“One of the challenges for our entire education system,” says Balassa, “is this dialog that says ‘manufacturing is dying.’” So students don’t tend to select into these programs … which will make it hard to sustain them.”

Why is it important to maintain skilled labor for manufacturers? These made-in-Oregon and exported out-of-state products bring “new money as opposed to circulating existing money,” says Balassa. State economist Beleiciks agrees, adding, “even if they’re not exporting, if they’re off-setting imports, it will have a similar effect.”

So aside from creating jobs, in-state manufacturing boosts tax revenues, provides income to Oregon stakeholders and induces development of necessary infrastructure.

Bringing actual manufacturing jobs back to Oregon will be an uphill battle. KEEN and Earth2o are only two examples of Oregon companies at the leading edge that may bring domestic manufacturing back from the brink.

Brandon Sawyer is research editor for Oregon Business. He can be reached at [email protected].

CORRECTION: This story was corrected on April 30, 2012, to change “outsouring mania” to “off-shoring mania” in the first paragraph. THE EDITORS.