A “tall timber” alliance aims to position Oregon as a front runner in the glamorous new world of wooden skyscrapers.

Created by the railroad, raised on timber jobs, Riddle, Oregon, population 1,180, has been ground down by timber’s downward spiral.

Gone are the gas station, grocery store, retail shops and most of the restaurants and taverns that once did steady business. Gone too is much of the hope in this hamlet located 24 miles south of Roseburg.

Now, an unlikely alliance of urban developers and architects, academics and timber industry executives may be about to reverse Riddle’s fortunes, and those of other timber towns, as they seek a new way of using trees to construct buildings.

The dream held by this “tall-timber alliance,” composed mostly of Oregonians (with one major exception), is to rebrand building with a revolutionary new green timber product, much the way Oregon chefs, restaurateurs and organic farmers rebranded local produce in the 1990s with the farm-to-table movement.

With the fervor of missionaries, the members of the tall timber alliance are putting mind, muscle, money and marketing savvy behind huge panels made of tree parts glued together. These panels, called cross-laminated timber panels, or CLTs, will be the building blocks of the next generation of the world’s skyscrapers, as well as more modest structures, alliance members insist.

The dimensions of these panels are mind-numbing, a fair match for the scope of the alliance’s vision. They come out of the production mill as large as 98 feet long, 18 feet wide and 19.5 inches thick. Created by a laminating process, they come off the assembly line long and sensuous, a quality perhaps unique to wood among building materials.

“People love the idea of living and working in a wood building,” says architect Thomas Robinson, principal of Portland-based LEVER Architecture, a firm that is working on a small office project in North Portland that will use CLT panels. “They are drawn to the material. Solid wood is attractive and it’s sustainable. Building with these panels will distinguish the product I offer to the market. It’s a way to connect urban and rural Oregon through design.”

According to the timber alliance script, most of the production and finishing work will be done in large facilities in timber towns, with assembly-only required on the actual building site. Like Legos on steroids, these panels come ready to assemble. They are set in place by huge cranes and fastened down tight. A CLT building goes up in a fraction of the time it takes to build with steel and concrete.

And they’ll be made in Riddle, Oregon, at least initially, by local laborers with D.R. Johnson Lumber, founded in 1951.

The company is run by one Valerie Johnson, daughter of the company founder. Born and bred in a timber town, she’s lived through the industry’s whipsawing fortunes and jumped at the opportunity to participate in the tall-timber alliance. She sees it as a chance to inject some life into the economies of timber communities like Riddle.

“My heart is with these good [timber town] people who know how to work hard. They’ve been through some terribly tough times. It’s just been a tragedy,” she says. “If the idea of mass timber construction and a renaissance of building with wood can move forward, it really puts people back to work with renewable resources.”

Sound like a long shot, a pipe dream, the result of city folks sharing a jug of corn liquor with the local yokels? After all, the world builds with steel and concrete. Trees are just placeholders, frames for the real building materials.

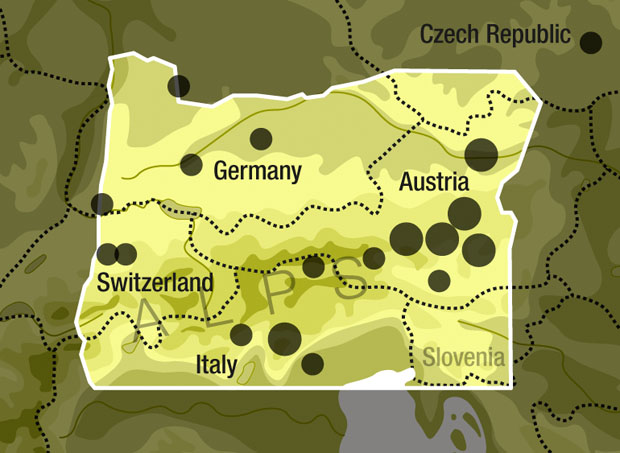

The alliance begs to disagree. They’re not inventing the process or the demand for it, they point out, since there’s already a flourishing European CLT industry in an area just about the size of Oregon.

The demand for the product is driven by its environmental and aesthetic advantages over steel and concrete, they say, and they predict rapid adoption of the building technique, with Oregon leading the way. “You’ll see tall-timber buildings in the U.S. within two years,” says Robinson.

The CLT movement is about far more than creating jobs for rural Oregonians. The acolytes’ vision is to brand wood construction — to market Oregon wood as a local, homegrown product. Some are already playing off the farm-to-table tagline by using the term “forest to frame.”

“CLTs are made from a renewable resource that we can produce at our back door [Riddle] and showcase at our front door [Pearl District],” says Portland developer Tom Cody. Cody, managing partner with Project Ecological Development, is moving ahead with plans for a CLT building in the Pearl District, a 135-foot-tall structure composed primarily of the massive wood panels. It’s critical to the success of his project to source the panels from an Oregon lumber company like D. R. Johnson, he says.

No less a marketing authority than Feast Portland co-founder Mike Thelin thinks the CLT recipe includes all the right ingredients. “Timber is symbolic and meaningful to this region, and we need to find a way to tell that story, and show people what it can look like,” says Thelin, a consultant who works on culinary real estate projects around the country. “The applications for these types of buildings are really beautiful. What’s so cool about this particular product is it enables you to create that massive timber-beam look without destroying old-growth forests.”

Thelin, Cody and other CLT advocates acknowledge there’s work to be done to brand timber from Douglas County the way heirloom tomatoes from Jackson County have been successfully branded. But they’ll also tell you the concept can’t miss; it’s just a matter of when, not if.

“Ideally, we keep this in a tight radius, we do it all in Oregon,” Cody says. “We have the opportunity to create something meaningful here. This can create a cycle of economic recovery in the rural communities that is directly supported by Oregon’s urban centers.”

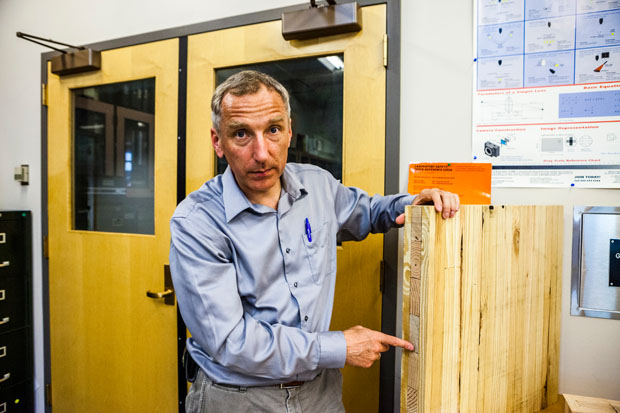

The professor: Lech Muszynski explains CLT construction in the OSU Forest Research Lab.

On January 6, more than 1,000 civic and business leaders listened, spellbound, as another CLT proselytizer made a similar pitch. The setting was the Oregon Convention Center, and the event was the Oregon Leadership Summit, an annual conference intended to rally support for the business agenda. It was a day full of thought-provoking lectures and panel discussions — about education, the fledgling drone industry and the infrastructure funding crisis. One speaker stole the show: Michael Green, a charismatic Vancouver, B.C., architect who travels the world promoting the game-changing virtues of CLT construction.

“Just like our food, we need to reproportion our diet so our buildings will be beautiful, local, healthy, fast and good for the planet,” Green proclaimed, as he wove together seemingly disparate issues — TV dinners, sustainable agriculture, urbanization, carbon emissions from the building sector — into a riveting narrative about how newfangled wood building can change the world.

The novel construction method, he said, can displace concrete and steel as a way to meet future demand for housing and business space — without further damaging the environment, and adding an aesthetic element that can bring a structure alive.

And Oregon, Green observed, is the place it can all happen. “This is an opportunity for Oregon to lead America, if not the world.”

|

Inside the D.R. Johnson mill in Riddle, Oregon. |

Here, Green believes, one finds all the elements for launching a CLT movement in the U.S.: a ready supply of the “junk” timber used in the process; a willing and able rural workforce; a timber industry infrastructure that can be readily adapted for CLT production; and a core of progressive architects and developers willing to experiment with new building methods.

The buzz at the Leadership Summit was instantaneous. “Fascinating presentation on next-generation wood building materials,” tweeted Multnomah County Commissioner Jules Bailey. “One of the most innovative thinkers in the world today,” said emcee Chris Coleman. “That talk was worth the price of admission,” remarked Tom Kelly, owner of the remodeling firm Neil Kelly Company and chair of the Portland Development Commission.

It wasn’t the first time Green hit the revival-show preacher’s jackpot in Oregon. In fact, the seeds of the tall-timber alliance were planted several years ago, when Dr. Thomas Maness, dean of the OSU College of Forestry, and Lech Muszynski, an OSU associate professor of Wood Science and Engineering, attended one of Green’s presentations. They were swept away by the vision Green painted of a built environment embracing tall structures made almost entirely out of giant CLT panels. The fact that Green could point to existing structures of more than 10 stories in Europe, Australia and New Zealand helped convince the academicians that the system could work in the U.S.

They in turn hosted a series of conferences and seminars designed to expose representatives of the building and timber industries to Green’s message. Their hope was that their natural partners for a CLT pilot project would surface.

They did. Today the nascent movement is barreling ahead at near lightning speed to ramp up an Oregon-based CLT industry. In addition to developers like Cody and architects like Robinson, one timber company executive stepped forward and agreed to give building the panels a shot.

Valerie Johnson’s father, Don R. “D.R.” Johnson, was a bit of a legend in the Oregon timber industry. He wasn’t afraid to push his lumber company into new markets, and in the 59 years he ran the company, he built an impressive privately held empire, with interests in eastern and western Oregon. His early ventures into the laminating and co-generation markets set the tone for the company, positioning it as a niche player, quick to test new markets.

His daughter succeeded him upon his death in 2010 and brought to the job her father’s feisty spirit. (The president of D.R. Johnson, Johnson co-owns the company along with several family members.) Johnson’s willingness to take on the project was critical not only to getting the pilot project off the ground, but to cementing the urban-rural partnership envisioned by Maness and Muszynski.

CLT manufacturers in Europe; OSU’s Lech Muszynski created the map to show the region is about the same size as Oregon. |

|

It’s hard to understate the risk the two agreed to take that day. Their own mill had been shut down due to lack of business. The investment they would have to make was unknown at that point, as was just about every other detail of how they would produce the massive panels that no other U.S. manufacturer had yet produced.

But in Johnson’s mind, the question was, “Would Don Johnson have taken this gamble?” The answer was a no-brainer. “My dad would have jumped on this,” she says.

But in Johnson’s mind, the question was, “Would Don Johnson have taken this gamble?” The answer was a no-brainer. “My dad would have jumped on this,” she says.

Less than a year after agreeing to participate in the pilot program, Johnson and Redfield were ready to produce their first panels. In that year, they attended more seminars and meetings on CLTs to get up to speed on the process. Johnson and Redfield took a whirlwind tour of the existing CLT production zone in Austria, Germany and Italy to see for themselves how the pros were doing it. Then, with internal and external funds ($50,000 from Oregon BEST), they assembled the equipment for the production line at the laminating mill in Riddle.

“We built quite a bit of this right here in our machine shop,” Redfield says with pride. On a wet day in February, Redfield is leading the way through the millworks to a section of the facility where the panels will be built. Gleaming new machines perched on thick cement slabs await their first orders. “We are ready to go,” Redfield says.

Being the first U.S. company to make CLT panels for tall-timber construction gives D.R. Johnson a serious competitive advantage, one that Johnson is keenly aware of and eager to exploit. (To protect that advantage, Johnson refused to let a photographer take pictures of the new machinery.) Just as her father got in early on laminated products and cogeneration, she wants to be at the forefront of the CLT business.

Muszynski believes her gamble will pay off. “Vision, guts and courage — that’s how I would describe Valerie Johnson and her company,” says Muszynski. “I can’t say enough about how great they are. They are as progressive as you get. And there’s plenty of demand out there for the product.”

John Redfield, chief operating officer, D.R. Johnson, in front of a sample house made from CLT panels.

The tall-timber industry is predicated on the economic and environmental benefits of a new green building construction material. But the wooden skyscraper movement is about much more than an innovative engineered-wood product. It also ushers the timber industry into the 21st-century branding economy.

As Thelin points out, forest products companies are not exactly known for their iconic or sexy marketing campaigns. Tall timber could change all that. Thelin, who became familiar with the mass timber movement as part of his culinary real estate work, sees a way to market buildings made from Oregon trees, felled by Oregon loggers, processed by Oregon timber mill workers, and used to create beautiful wood buildings designed by Oregon architects. These buildings would leave behind a much smaller carbon footprint than the conventional steel-and-concrete structures that dominate every city in the world today.

“There’s a lot of buzz around this,” Thelin says. “People in the building industry are really excited.” The next step is to connect the dots for consumers, says Thelin, who believes the alliance should come up with something more precise than the current tagline, forest-to-frame. “Show me a building that isn’t ‘forest-to-frame,’” he says.

For her part, Johnson seems to intuitively understand the urban-rural connection that the other members of the alliance want to pursue. Her presence at the Oregon Leadership Summit — she spoke immediately after Green, receiving at least as much applause — was a concrete and symbolic representation of the CLT business model. Born and raised in rural Oregon, Johnson worked for her father’s company and lived the vicious and often demoralizing cycles of the timber business. Like her father, she supports conservative causes and has represented timber interests in environmental debates. But for years she has lived in the Portland metro area, handling her management chores virtually from the city.

For her part, Johnson seems to intuitively understand the urban-rural connection that the other members of the alliance want to pursue. Her presence at the Oregon Leadership Summit — she spoke immediately after Green, receiving at least as much applause — was a concrete and symbolic representation of the CLT business model. Born and raised in rural Oregon, Johnson worked for her father’s company and lived the vicious and often demoralizing cycles of the timber business. Like her father, she supports conservative causes and has represented timber interests in environmental debates. But for years she has lived in the Portland metro area, handling her management chores virtually from the city.

Johnson would love to make a lasting contribution to the revival of Oregon’s rural economy. That’s why she was willing and eager to bring D.R. Johnson to the CLT table when its Oregon advocates came looking for a timber partner.

But she doesn’t want to raise the hopes of rural Oregonians unrealistically, either. “I don’t know that we always can foresee how an idea will evolve,” she says. “If the idea of mass timber construction and a renaissance of building with wood can move forward, it really puts people back to work with renewable resources. But this isn’t going to be a huge facility initially, just a handful of new jobs. There’s a lot of work to be done before we’ll know what this is going to look like.”

The success of CLT manufacturers in Europe serves as a beacon for Oregon’s timber-tower alliance as they attempt to re-create the industry in Oregon. But, as Johnson says, there’s work to be done first to grow an industry — in both the public and private arenas.

Among the challenges is wood’s historic reputation as tinder for a great city fire — in London, Chicago and San Francisco, for example. In Oregon, both the materials and the panels themselves will have to be thoroughly evaluated so that building code officials can be convinced these materials will meet strength, seismic and fire safety standards. Currently, most U.S. codes don’t cover such materials, or if they do, they are for wood buildings of only a few stories in height.

Another concern is the timber industry’s overall lack of response to date to the CLT challenge. Oregon State University invited representatives of three timber companies to its presentations on CLT, seeking partnerships to launch a pilot program. But only Johnson offered to help kickstart the program. Should demand for the product take off, more than one company would have to produce the panels to meet demand.

Another concern is the timber industry’s overall lack of response to date to the CLT challenge. Oregon State University invited representatives of three timber companies to its presentations on CLT, seeking partnerships to launch a pilot program. But only Johnson offered to help kickstart the program. Should demand for the product take off, more than one company would have to produce the panels to meet demand.

Building a dependable workforce is yet another challenge. It’s one thing to have the technology and the facilities to build cross-laminated timber panels. But someone who knows what they’re doing has to show up to do the work. A skilled labor force must be developed locally in order to produce the CLT panels.

Perhaps the most pressing issue to be addressed is the environmental impact of producing the panels. As Green’s presentation notes, buildings produce a whopping 47% of all carbon emissions. While the wood panels may offer substantial carbon advantages over steel and concrete, their production requires laminating materials like resins and epoxies “that can make products that are either harmful to the environment or that are not,” developer Cody says. “We’re interested in the nonharmful ones.”

Members of the alliance say they are working on all of these problems. OSU intends to establish a testing center to evaluate all aspects of CLT construction, and is also developing a new program to build workforce competencies. Meanwhile, Oregon’s building codes division, already one of the most progressive in the country, is looking to accommodate the new construction.

“We’re supportive of the CLT process,” says Andy Peterson, manager for plan review and permitting at the Portland Bureau of Development Services. Peterson believes that the “rigorous testing” the materials will undergo will pave the way for its inclusion in the state building code.

| Reach for the sky: A rendering of a planned CLT project in the Pearl District, a 135-foot mixed-use building |

“You can look around the world and see where some of these tall wood structures have been built. We’re all learning from one another.”

It’s a global learning process, this brewing revolution within the built environment community that dares to challenge 150 years of erecting tall buildings with concrete and steel. It reads like fiction when you put it all together.

There’s the Canadian architect who hitched his star to a massive wood panel and now stumps North America to promote CLTs. His converts from Oregon — Green is considering opening an office in Portland — find their forest-products soulmates, who in turn drink the Kool-Aid and think they can brand a giant wooden Lego as “Oregon grown and Oregon built.”

A few timber veterans from Riddle decide to drink it too, and find themselves winding through a huge Austrian CLT factory, frantically asking questions and taking notes. They return to Riddle, a bit shaky but energized, and start the task of passing on the knowledge to their workers, hoping they’ll get it right so they can grab the CLT brass ring before some other timber company gets there first.

It’s a legitimate concern. Last year an Austrian manufacturer announced plans to partner with an Idaho lumber mill to market and produce CLT panels. The federal government is underwriting several CLT initiatives, including a $2 million White House prize competition to design and build high-rise structures out of wood.

As these grand plans unfold, the residents of Riddle continue to get up in the morning, go about their business, have a good meal at dinner time and turn in, unaware they are in the middle of something that could be very, very big for Oregon. Something that could at last bridge the yawning gap between rural and urban. Something that could rival farm-to-table as a marketing concept. Something that could be the Next Big Thing on a global scale.

And it might even bring the gas station back to Riddle.

A version of this article appears in the April issue of Oregon Business.