Spiking prices and insatiable demand produce a record-breaking season for Oregon’s farmers.

Spiking prices and insatiable demand produce a record-breaking season for Oregon’s farmers.

By Ben Jacklet

Midway through the frenzy of the harvest, Oregon Wheat Growers League president Kevin Porter found himself working as truck driver for the day. His job was to load a thousand bushels or so of wheat into a 70-foot rig, haul it off to the McNary Grain Elevator by the Columbia River, return for another load, and repeat, all day long. Out in the fields, three combines were cutting 30-foot swaths of wheat nonstop and offloading without slowing. By day’s end 10 people, 10 machines and $3,000 worth of diesel fuel had harvested 300 acres of wheat and loaded it into storage for export.

Efficiency is nothing new in Oregon wheat country. What has changed is the money.

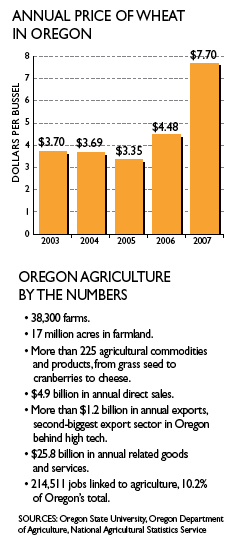

“For 95% of my career I sold wheat for less than $4 a bushel,” says Porter.

|

Not any more. The wheat price was hovering at around $8 a bushel during the harvest, and if global grain supplies remain constricted and Australia suffers through its third consecutive year of drought, the price is expected to bump up even higher. Wheat hit a record $16 per bushel in February, and while prices have dropped to earth this summer, the market remains strong. Oregon wheat farmers have the option of selling early for twice the price they’re used to getting, or holding out for more.

Wheat growers aren’t the only farmers harvesting with a renewed sense of urgency this season. Spurred by the weak dollar and the ethanol boom, the global marketplace is starved for wheat, hay, grass seed and other major Oregon exports. Prices are up for the vast majority of Oregon’s 225-plus agricultural products with the sad exception of onions. No wonder the Oregon Department of Agriculture is forecasting record revenues.

Agriculture and timber were the engines that powered the Oregon economy for its first 100 years. Both engines began sputtering in the 1980s and have been running rough for decades. Wages in the state’s rural counties have declined, and rural economies have stagnated. But while the timber industry’s struggles have intensified during the current downturn, Oregon agriculture has bounced back powerfully. That’s good news for rural Oregon, or at least the portions of rural Oregon not reliant on the timber industry.

In 2007, Oregon farmers harvested nearly $5 billion in sales and generated an estimated economic impact of $25.8 billion in sales and 214,511 jobs. All those numbers are expected to grow significantly this year, as high prices for everything from hay to hops are compelling farmers to expand, upgrade and invest. Blueberries, corn, wheat and hops are on target for record sales. “Everything else in the economy is on a downturn, and we’re flying high in almost every category,” says Don Schellenberg, assistant director of government affairs for the Oregon Farm Bureau.

|

The strong market for agricultural exports helped convince a major Japanese shipping line, K Lines, to resume service to Portland in July after a four-year hiatus. Exports of Oregon agricultural and processed food products in the first quarter were worth $978 million, which Brent Searle of ODA called “an amazing number and nearly equal to the entire annual [agricultural] exports a couple years ago.”

Unfortunately for farmers, the costs of diesel, fertilizers and farm chemicals are rising just as rapidly as are crop prices. But they are getting paid well enough for what they produce to invest and expand. Agricultural sales trickle far and wide through the Oregon economy, from the John Deere dealership to the grocery store to the farmland real estate market. More money in farm sales means more money for food processing, agricultural services, retail and wholesale trade, transportation, and warehouse storage. Companies such as Ag West Supply, founded in 1932 with five locations in Oregon, are benefiting from the uptick. “We’ve built an aggressive sales plan and we’re ahead of that right now,” Ag West general manager Steve Danner said. “There’s a lot of concern about expenses but there’s a lot of optimism too. We’re expecting a very strong fourth quarter. There’s a lot of older equipment out there that needs to be updated.”

“I know a lot of farmers who are doing maintenance on their equipment that they haven’t done in 20 years,” says Donald Horneck, an agronomist for the Oregon State University Extension Service. “All you have to do is check out the John Deere dealership. You won’t find a single piece of big equipment available there. Everything’s sold out.”

|

Commodity prices also are reawakening demand for farm properties. The average value of Oregon agricultural land hardly changed between 2002 and 2005, increasing minutely from $1,185 per acre to $1,192 per acre. From 2005 to 2008 it grew by 51% percent to $1,800 per acre.

“The value of agricultural land has increased and the biggest reason for that is the commodity prices,” says Deb Sue Hamby, a Pendleton-based loan officer with the Northwest Farm Credit Services bank. “There have been a lot of outside investor buyers that have been coming into the area buying up land.”

Of course, outside investors have been trying to get their hands on Oregon agricultural properties for years. The difference is, now the speculative goal is not to build subdivisions or golf courses, but to keep it farmland, because with prices soaring, farming is where the money’s at.

Imagine that.

Kevin Porter has been working the dry- land wheat country west of Pendleton since he was 16 years old. When he began working full time at the farm in 1994 it was 1,600 acres. Today he and his brother-in-law Tom Sorey manage a combined 10,000 acres. Between them they own three combines, four semi trucks, three grain trailers and three “bank-out wagons” to transport the wheat from the combines to the trucks. Their harvest lasts roughly 25 15-hour days: up by 5, off to the fields by 7 and home by 10.

Cruising down the dusty road hauling another 1,100 bushels to the river, Porter says he loved growing wheat long before there was money in it. His nearest neighbor is a mile and a half away. His kids get to run around in a 650-acre back yard. He survived the hard years by keeping his operation lean and efficient but growing it as well, investing carefully in new land and equipment, which he bought used with partners.

For Porter and other Oregon wheat farmers, the payback for a decade of stagnation came last fall, when prices doubled and kept rising from there. In 2006 the Umatilla County wheat crop earned growers $66 million. In 2007 that figure jumped to $109 million, and it could have risen higher still if more farmers had ridden the price wave upward. “Last year was a very good year,” Porter says. “No doubt about it. Unfortunately a lot of that $16 wheat that you heard about sold for $6. That’s because most people had never seen $6 wheat, so as soon as the price hit $6 they sold.”

Growers are unlikely to repeat that mistake this year. John Sperl, grain division manager for Pendleton Grain Growers, a 2,500-member cooperative that operates the 3 million-bushel capacity McNary elevator in Umatilla, said, “most of the growers are holding and waiting. A lot of people kicked themselves for selling early last year.”

Other growers failed to capitalize on the price hike because they were locked into long-term contracts with the federal government to conserve the soil by not planting. Nearly 160,000 acres in Umatilla County and 565,000 acres statewide are in the Conservation Reserve Program, which pays farmers for not farming.

For growers who kept their land in production and timed their sales well, 2007 was a banner year. Oregon wheat sales rose from $198 million in 2006 to more than $360 million in 2007. Farmers planted an additional 150,000 acres of wheat to capitalize on the price bump. Debts were paid off, long-overdue maintenance was performed and sales at farm equipment outlets were brisk. “We began to see a glimmer of hope, and people started upgrading,” says Tammy Dennee, executive director of the Oregon Wheat Growers League. “If we can hold into this and build on it, we will see wealth and prosperity in the countryside that we haven’t seen for decades.”

But Porter and Dennee emphasize that it will take more than one banner year to compensate for a decade of drought and low prices, especially with diesel selling for nearly $5 a gallon and fertilizer costing twice what it did a year ago. “There was a lot of euphoria last year when that price kept going up,” Porter says. “Now there’s a lot of fear about what might be the downside.”

Mike Krueger, president of Wilsonville-based MK Commodities, has been tracking the price of wheat since the 1960s. He says a lot depends on the weather in Australia, Oregon’s biggest competitor for supplying soft white wheat to Asia. Until Australia recovers from its persistent drought problem, Krueger says, Oregon’s position will remain strong.

|

“The farmers are in a very good position for the first time in at least 10 years,” Krueger says. “A lot of them had one hell of a time getting through the hard times but if they’re still standing they are looking at some real opportunities now that the market’s going the other way.”

About 230 miles west of Umatilla County’s arid wheat country, the green fields of the Willamette Valley are lush with growth. Cruising past healthy rows of nursery trees, corn, blackberries, hazelnut trees, wheat and green beans, berry farmer Doug Krahmer has nothing but praise for the climate, soil quality and crop diversity of the Willamette Valley. Krahmer is glad he invested in farmland here when he did. He figures that valley land prices have doubled if not tripled since he bought most of his properties in 1999 and 2000.

Krahmer got into blueberries in 1996 with one leased eight-acre field. From that modest beginning he has built Blue Horizon Farms, an 800-acre, five-county network of berry fields from Clatskanie to Albany that yields about 2 million pounds of blueberries per year. He also runs BHS Ag. Services, a year-round operation specializing in pruning, harvest and planting. Between the two operations he employs 35 people year-round and 150 seasonal workers.

“The price has been really good for the past five years,” he says. “That has allowed us to expand.”

Krahmer and his peers are riding a wave of demand that stretches from Oregon’s popular U-Pick farms and farmer’s markets to the frozen food aisles of domestic grocery stores, to fresh and processed foreign markets in Japan, Mexico and France. Oregon’s blueberry crop nearly doubled in value over three years, from $33 million in 2005 to $65 million in 2007.

|

Other specialty crops in the valley such as hazelnuts and hops are also doing extremely well, and the bump in commodity prices has encouraged a massive shift back into Willamette Valley wheat. Valley farmers who followed the money years ago from wheat to grass seed followed it right back to wheat in 2008, building makeshift wheat storage areas and securing last-minute freight rail contracts to get their crops to the grain terminals of Portland for export. Unlike dry-land farmers east of the Cascades, the farmers of the valley have many crop options, so they are accustomed to following markets and planting accordingly. They did not benefit significantly from the commodity price increases last year, but they are expected to capitalize in 2008 and 2009.

As chairman of the Oregon Blueberry Commission and a member of the Oregon Board of Agriculture, Krahmer is acutely aware of the risks and opportunities stemming from the current volatility of world markets. He sees great potential in exporting to the burgeoning middle classes of India and China, but like most farmers he identifies the recent price bumps as a double-edged sword. Yes, farmers are making more money (Krahmer rotates wheat on his fields to prepare the soil for berries and was happy to earn income from that crop for a change last year); but at the same time fuel and fertilizer costs are “eating us alive,” he says.

Krahmer invested early in technology to cut labor costs and improve efficiency. He can monitor soil moisture at all his fields from any computer with an Internet connection, and his tractors steer automatically while planting rows using global positioning satellite technology.

He owns five mechanical harvesting machines. About 90% of his berries are machine-picked for the frozen market, with the remaining 10% hand-picked to sell fresh. It costs him more to pick by hand, but the cost difference is more than covered by the $1.30-$1.50 he is receiving for fresh berries. His margin is actually slightly better for hand-picked fruit.

But Krahmer has no intention or desire to go small scale. He has built his company on volume and efficiency, and like large-scale farmers throughout the state, the best he can do for now is hope that crop prices remain healthy enough to offset the ominous rise in prices for diesel, nitrogen and everything else.

Other risks also loom for farmers: the possibility of stricter immigration laws creating a labor shortage, a regulatory crackdown on commodity speculation that could lower prices for export goods, a global race to plant and harvest more food that could lead to oversupply. The more farmers invest during times of plenty the more they risk falling prey to the bursting of yet another bubble in an unstable global economy.

“The greatest fear everyone in farming has is that prices will collapse and we’ll be stuck with high costs for fuel and fertilizer,” Horneck says. “Farming has never been cheap. But it has gotten vastly more expensive. Fortunately the prices are saving a lot of people, and it’s high time that happened. We’ve had plenty of experience being on the bottom. I’ve been in this business since 1980 and there’s never been a time when farmers have been able to call the shots like this.”

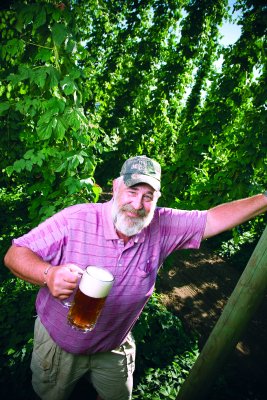

On the other side of the Willamette River, surrounded by healthy fields of trellised vines, Mount Angel hop grower John Annen is hoping that once he has fulfilled his contracts with the Hops Union and Anheuser Busch, he will have a nice supply left over for the open market. Because the open market for Oregon hops is stronger than ever.

A decade ago hop farmers were oversupplying the market. New processing technologies were enabling a longer shelf life for their product, while new brewing techniques were allowing brewers to use hops more efficiently. “We had hops processed and waiting in storage at room temperature that we couldn’t sell,” says Michelle Palacios, administrator of the Oregon Hop Commission. “We had to drop annual production under demand to move hops out of storage and boost the price. By 1998-99 we had taken out one-third of our hops acreage.”

The price bottomed out at $1.20 per pound. Hop growers subsidized their crops by delving into more profitable products such as nursery trees and hazelnuts. But with time the cut in production whittled away their oversupply problem, and eventually reversed it. Then came the hops warehouse fire of 2006 in Yakima, Wash., when 10 million pounds of hops went up in smoke. Suddenly the balance was tipped the other way. The price recovered to $3.50 last fall and then shot up to $10 and even $20 per pound when supplies became scarce. Oregon hop farmers pounced on the opportunity by planting an additional 522 acres, repairing picking machines and purchasing new tractors, irrigation systems and sprayers. For the first time in years there was a market for new 22-foot treated-timber hop poles.

Annen’s great-grandfather started growing hops in Mount Angel in 1896. His family invested in its first mechanical picker in 1952 and dried the hops in a wood-fired furnace. Today Annen Brothers has 270 trellised acres of hops, a modern picker, kilns fired with natural gas, a four-floor drying facility, an automated drip irrigation system to keep the soil saturated to 65% at eight inches and a pest management strategy that far outperforms the “scorched earth” techniques Annen remembers from his youth.

Annen also has entrepreneurial plans to develop a new product to serve Oregon’s healthy brew-pub and home-brewer market: 15-pound bales of specialty aroma hops, direct from the farm, packaged in zip-top baggies, distributed through Hops 2 You, a company he established with his partner Jeff DeSantis, the owner of Seven Brides Brewing in Silverton.

Annen doesn’t trust the prices to last. He says he is fortunate to have contracts in place “to isolate us from the crash when it comes.” But he is also more than happy to make the most of the price while it lasts.

“Every grower is happy when the price is up,” says Annen. “For years it was so down that everyone was driving around on ancient equipment and barely getting by. It was high time that everybody got a nice boost so they can get some new toys and get some innovations going and give our employees a bump. When the economy is good, it’s good for all of us.”

|   |

Doug Krahmer built Blue Horizon Farms in the Willamette Valley from eight acres in 1996 to 800 acres.

PHOTOS BY FRANK MILLER

|  |

| John Annen enjoys the fruit of his labors surrounded by a banner crop. |

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]

A wheat combine at WP Farms, west of Pendleton, cuts a 30-foot-wide swath of grain for export.

A wheat combine at WP Farms, west of Pendleton, cuts a 30-foot-wide swath of grain for export.