Capital poor and risk averse, Oregon has never been known for fast money. But an ambitious group of young business leaders is working to reinvigorate the startup scene.

Capital poor and risk averse, Oregon has never been known for fast money. But an ambitious group of young business leaders is working to reinvigorate the startup scene.

THE NEW DEAL

STORY BY BEN JACKLET // PHOTOS BY ANTHONY PIDGEON

|

Left to right: John Friess of Starve Ups, Mark Grimes of Ned.com, Eric Doebele of ReliableRemodeler.com, Josh Friedman of NedSpace, Nitin Khanna of MergerTech and Ryan Buchanan of eROI and the Software Association of Oregon. All are involved in a multi-pronged effort to boost Portland’s startup scene. |

Eric Doebele timed his first major exit nicely.

In 2007, the Beaverton web company Doebele co-founded with his business partner Jack Phan, ReliableRemodeler.com, was one of the nation’s fastest-growing private companies. By the following February, just as the economy was poised to crash, Doebele and Phan sold their company to the online marketing giant QuinStreet for $25.5 million.

The moment the deal closed, Doebele’s life was changed. But the 37-year-old entrepreneur, born and raised in Kelso, Wash., did not leave Oregon. Nor did he step back from the business world to pursue other interests. Instead he immersed himself locally, tapping into Oregon’s angel investing community and looking around for companies to invest in and mentor. Before long he had compiled a portfolio of a half dozen burgeoning Portland technology companies to support. He invested between $25,000 and $50,000 in each of these businesses, to keep them going but also keep them hungry, with the ulterior motive of giving the economy a boost.

“When you invest money in a startup, that money goes right back into the economy,” says Doebele. “When an entrepreneur gets money in his hands, he’s hiring somebody. He’s putting somebody to work the next day. It’s short-term job creation that’s local. But you’re also creating something for the long term. Small business is what drives the economy. And you’re planting the seeds for tomorrow’s mid-sized companies.” Doebele’s investments were particularly welcome given the difficulties so many small businesses are experiencing getting access to capital in the still-sluggish economy. Not only has he boosted the prospects of several nascent Portland businesses with serious potential, he has deepened his ties with an energetic team of young business leaders with big ideas about how to jump-start the state’s startup scene.

|

Eric Doebele decided to stay in Portland after his successful exit from ReliableRemodeler.com in 2008. Since selling that business he has been investing in and mentoring a half dozen promising Portland tech startups. |

|

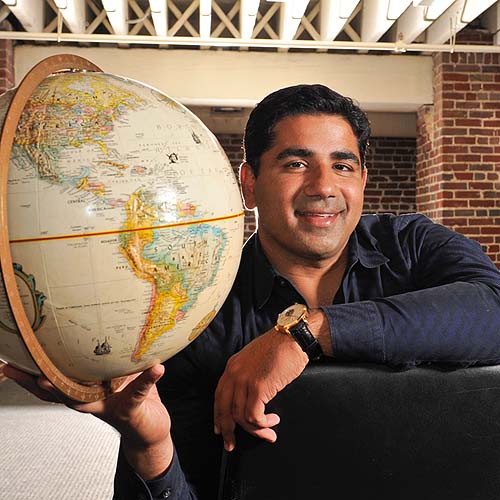

Nitin Khanna built Saber Consulting into a 1,500-employee business in less than a decade before selling the company for $420 million in November 2007. He is launching an M&A firm, MergerTech, and investing in five local startups. |

Mark Grimes, co-founder of the shared work environment NedSpace, has launched four businesses and invested in a dozen others, as well as helping to organize a Maker Faire in Ghana and launching a philanthropic water service. |

Doebele and his informal partners in this quest — Josh Friedman and Mark Grimes of NedSpace, John Friess of Starve Ups, Nitin Khanna of MergerTech, and Ryan Buchanan of the Software Association of Oregon, just to name a few — make a lively team. They spend a lot of time at the Backspace Café in Portland’s Old Town, a quirky establishment with abstract art on the walls, video game terminals and vegan baked goods on the menu, and whether it’s a result of all the caffeine or their inherent enthusiasm for ideas and action, they tend to speak extremely quickly and cover a great deal of philosophical territory in their discussions. They are the sorts of interview subjects who can barely wait for the question to finish before letting loose with an answer. Their discourse ventures far and wide, but strong themes rise to the top: the power of collaboration, the importance of peer mentoring and the need for more entrepreneurial support in Oregon.

Perhaps more important than their shared traits and ideas are their shared experiences, of starting a business from nothing, building it into something of value, and, if and when it becomes possible, selling it at the best price, to begin the cycle again, from a position of greater power. They dove into the technology sector during a time of great opportunity, survived the Internet crash one way or another, and have survived the Great Recession as well. They’ve learned how to do a lot with a little bit of money, but they also recognize the importance of fast money, delivered early in the process when the entrepreneur needs it most.

Oregon has never been known for fast money. Compared to robust West Coast startup scenes in Seattle and San Francisco, Portland’s has suffered from lack of capital and aversion to risk. Relatively few venture capital funds operate here, and individual “angel” investors are understandably cautious about pouring their savings into unproven enterprises. Fewer risks mean fewer rewards, fewer millionaires pouring their newfound wealth back into the economy by launching new enterprises or supporting fellow entrepreneurs.

The problem is long-standing and well known. What to do about it?

One idea espoused by Friedman and Grimes of NedSpace involves setting up an aggressive new seed fund supported by the City of Portland to finance multiple early- stage businesses quickly and systematically. Another idea, articulated by Khanna, involves building local startups into acquisition targets and setting ambitious goals for dramatic payouts. Yet another idea, embraced by Friess and the Starve Ups crew, involves collaboration between the founders of local technology businesses and an almost Masonic dedication to a cycle of creating businesses, growing them, selling them for maximum reward, investing those rewards and creating again.

Taken as a whole, their ideas add up to a compelling master plan for reinvigorating the startup scene — and the economy.

|

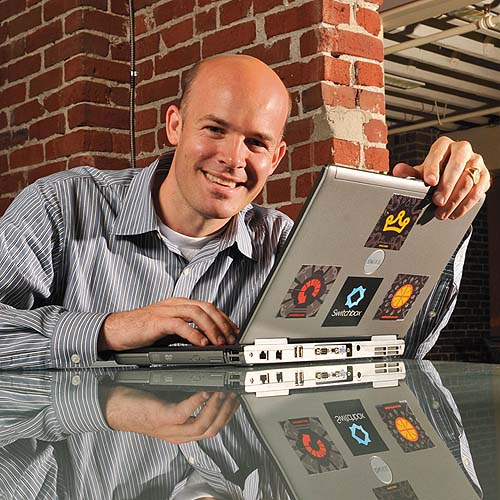

Josh Friedman (pictured with NedSpace mascot Ace) co-founded Eleven Wireless in 2001 and hopes to launch a seed fund to boost similar start-ups with early capital. The City of Portland has committed $500,000 to such a fund. |

|

John Friess credits the collaborative approach of the Portland peer mentoring group Starve Ups for the $7.5 million sale of his first company, Wired.MD. His new company is Journey Gym, selling portable gyms for travelers. |

|

Ryan Buchanan, the 35-year-old chairman of the Software Association of Oregon, has built his online marketing business eROI into one of Oregon’s fastest-growing companies. He’s also on the board of Starve Ups. |

Josh Friedman and Eric Doebele have been friends for years. They worked together for College Pro Painters in their early 20s, where they learned the basics of starting and running businesses. Both are youthful, fit, brimming with energy and hypersocial, pausing frequently to greet the steady flow of patrons wandering in and out of the Backspace Café.

Friedman, a graduate of Portland’s Wilson High School and Oregon State University, worked for Intel in the late 1990s and TripWire around the turn of the century. Both companies served as great learning environments, but it was during his tenure at Intel, when part of his job involved studying potential investments for what would later become Intel Capital, that Friedman recognized what he really wanted to do with his life. He’s been an entrepreneur ever since. He co-founded Eleven Wireless in 2001 to capitalize on the then-nascent market for wireless Internet connections to hotels, and while his timing was not fortunate, he did manage to avoid running out of money and, with time, build a profitable company.

Friedman is no longer involved in the day-to-day operations of Eleven Wireless, but he is far from dormant on the startup scene, where he seems to know pretty much everyone. He co-founded NedSpace, a co-working office space in downtown Portland for tech entrepreneurs, with Mark Grimes last year, and as a side project to that popular initiative the two have been working with a group of investors behind the scenes for the past year to create a seed fund. The idea of the fund is to leverage support from the City of Portland to raise $3.5 million to $5 million from private investors, with the goal of systematically feeding Portland’s startup pipeline with small but crucial investments similar to the checks that Doebele has been writing.

Looking back on his experience starting up Eleven Wireless, Friedman, now a wizened 36 years old, says it was difficult to raise money. “Yes, I was a first-time CEO and we had a young founding team. But we had a good idea. We were a leader in the space. If we were in any other city, if we were in Seattle or San Francisco or Boston or Austin or New York City, we would have been funded like that.”

In Friedman’s view, lack of early-stage capital is a “cyclical problem” in Portland. “We have amazing angel investors here,” he says, “but because we haven’t had numerous large successes with young entrepreneurs, there’s not a lot of money going into high-risk deals. So the angel investors tend to be much more conservative than in other cities. They don’t let money go easily. They don’t take a systematic approach to investing. And all of those things are required for an angel community to thrive.”

The problem is serious in Friedman’s view because “for many people if you don’t get seed money, you can’t start the business. You can’t quit your job and leave your house and make the commitment.”

Friedman says the idea of starting a seed fund with public sector support came from Wayne Embree, a longtime Oregon investor who meets frequently with Friedman, Grimes and Harvey Matthews, the former president of the Software Association of Oregon and a creator of the Oregon Investment Fund. In March 2009, the group staged a rally at NedSpace downtown, inviting dozens of entrepreneurs to take the stage and introduce their business ideas and their plans for creating wealth and jobs in Portland. Hundreds of people attended, including Portland mayor Sam Adams and his economic policy adviser Skip Newberry.

Friedman, Embree and Grimes subsequently met with the mayor, and talks ensued with the Portland Development Commission. In February, the city announced it would support a new Portland Seed Fund with $500,000. The new fund will not necessarily be managed by Friedman’s team, which consists of himself, Mark Grimes, Willamette University professor and angel investing expert Rob Wiltbank, and Brewster Crosby, an investor and CEO of the Portland marketing startup Gliffik. The Oregon Entrepreneurs Network is also putting forth a proposal to manage the fund, and other groups may offer proposals as well. The city plans to choose a fund manager by Aug. 20.

“We want to win the money,” says Friedman. “We started the effort. But may the best man or woman win. No matter what happens, it will be a good thing.”

|

The NedSpace/Starve Ups ethic values collaboration over competition, giving rise to a tightly knit community of young Portland entrepreneurs. |

Friedman’s partner in launching NedSpace and proposing the new Portland seed fund, Mark Grimes, is much older than most of his NedSpace peers at 48. But it would be hard to find an entrepreneur younger at heart.

Here is how Grimes describes his exit from the first of four businesses he has launched: “After about two years I got bored, sold it, started doing other things.”

Here’s his take on innovation: “The half-baked notion where you don’t even know what the product is or what the market will be, that’s what’s exciting to me. That’s where true innovation comes from.”

Grimes says all of the companies he’s founded, including the web advertising agency he launched in 1996, Eyescream Interactive, were profitable within 90 days in spite of not having business plans. But he got hit badly by the dot-com crash and Eyescream collapsed in 2001.

“A handful of really bad things happened as a result of having a five-year lease with a personal guarantee,” says Grimes. “It was not a pleasant time, but we did not have to file for bankruptcy and all the staff was paid.”

Even that grisly business experience could not beat the entrepreneurial zeal out of Grimes. He’s invested in a dozen companies in Portland and San Diego, launched a philanthropic water service, helped organize a Maker Faire in Ghana and placed more than 7,000 loans through Kiva, an online micro-lending program that connects investors from rich countries with entrepreneurs in poor countries. He hopes to take the NedSpace concept, a “cross-pollination of experience and ideas” as he describes it, and expand it nationally along with the high-volume, small-scale seed fund that he believes would complement it neatly.

His vision for such a fund involves seeding between 20 and 50 companies per year with $25,000 to $100,000 each. Grimes insists that spreading the investments widely would produce better results than mega-investments in one or two enterprises (think ethanol plants). “Are a third of them going to fail? Absolutely. We’re going to say that going into it,” he says. “Or maybe 20% or 25% will fail. But plenty will succeed. And what’s fail anyhow? If it employs people for a year and brings in taxes, is it a failure?”

Grimes argues that the successes resulting from such a program would bring further successes, improving Portland’s reputation as a city eager to host entrepreneurs, as opposed to an environment hostile to business. “If money is flowing through the city to start-up companies, people will move to Portland to start up companies,” he predicts. “You can do amazing things for startup companies with just $25,000 to $100,000.”

One of the reasons Eric Doebele likes to keep his investments small is because he believes it is much cheaper to start new technology businesses than it used to be. Tech expenses that used to run millions of dollars now cost several thousand dollars per month, and innovators can test new ideas much more efficiently than in the past. “You can get the proof of concept at a much lower cost, and the feedback comes much faster,” he says.

Doebele’s deep experience in the high-growth technology sector is as valuable as his cash to the local startups he is supporting. In addition to investing in local companies, he is mentoring the founders of companies such as the online rent payment business Paydici and the vacation home rental business Second Porch. He meets with the leaders of these companies and others regularly, sharing his experience in starting and growing ReliableRemodelers.com and selling it for maximum reward.

He is not the only entrepreneur following this path. If Doebele did well with ReliableRemodeler.com, Nitin Khanna did amazingly well with Saber Consulting. The 39-year-old Khanna became an instant multimillionaire when Saber was acquired by Ross Perot’s EDS for $420 million in November 2007.

Khanna grew up in a family that controlled the supply of coal and wood in northern India. The son of a military man, he moved constantly during his youth in India and continued that restlessness into adulthood, attending four different universities in the U.S. and growing quickly bored with his job at Oracle, leaving in 1998 to start Saber with his brother, Karan.

“Our model was rapid development and knowledge transfer. We thought the biggest companies weren’t doing these things well at all. To them rapid was three years. For us it was six months.”

Success came quickly for Khanna’s Salem-based business, which specialized in technology for election systems and unemployment benefits. “Our first-year revenue was 200 grand. Second year we did 800. Third year we did two-and-a-half million. Fourth year we did six-and-a-half million.” (Khanna is not reading from notes as he reels off these numbers and others. He knows them by heart.)

Growth became even more astronomical after Khanna and his brother tapped into private equity to buy a company three times as large as Saber in 2006. By the time they sold Saber, Khanna says they had 1,500 employees and were winning 100% of the projects for which they were bidding.

With his swashbuckling demeanor and unapologetic devotion to material wealth, Khanna would seem to hold more in common with the entrepreneurs of Orange County or Silicon Valley than Portland. But his children are in Portland, and he has decided to stay. He recently purchased the penthouse suite at the John Ross condominium in Portland’s South Waterfront neighborhood and like Doebele he has invested in five local startups. In addition, even though his days are full as he and his brother launch a global mergers and acquisitions firm called MergerTech, he dedicates a day and a half per week to mentoring local entrepreneurs, giving nine speeches over the past two months with titles such as “How to Double Your Revenue Every Year” and “Acquiring the Acquisition Mindset.”

Khanna also joined the Portland peer mentoring group Starve Ups last December, although he is far from starving.

Local entrepreneurs are thrilled to have Khanna in town. “Nitin’s support of start-ups has been second to none,” says Portland entrepreneur John Friess. “If he weren’t in town, a lot of companies would be in worse shape than they are. He is changing the entire city.”

Khanna says he has been impressed with the mentoring and support groups for local entrepreneurs such as Starve Ups, the Oregon Angel Fund, the Oregon Entrepreneurs Network and the Software Association of Oregon. But he is highly critical of the state’s shortcomings in seeding companies with potential to grow powerfully. “The angel scene in Oregon is unbelievably onerous on the entrepreneur,” he says. “The amount of work required to get as little as $25,000 to $100,000 is abominable. The things I would really like to see in Portland are an increase in angel money and an increase in the velocity of that money.”

He also wants to convince the founders of local tech companies to aim higher as they look to sell their businesses. Much higher.

John Friess was 23 years old when he and his brother launched Wired.MD, the first company to stream patient education videos into the exam room.

“This was in 1999,” he says, grinning and speaking loudly over the late-afternoon din of the Backspace crowd. “You could write a business plan, launch a software application and get acquired about six weeks later. Naively we were thinking this was going to be a year, maybe two years. It’s been 10 years.”

Friess and his brother Mark founded Wired.MD on March 13, 2000. On April 14, 2000, the tech bubble burst. It took time and work, but they survived the bust, with more than a little help from their peers.

As the crash was playing out, Friess found himself standing in the Oregon Zoo parking lot one evening after an Oregon Entrepreneurs Network event, talking with a circle of tech company founders for hours. “I realized that this was the most valuable interaction possible,” he says, “other founders of other start-ups, talking about the problems and solutions we had found. We were joking we should start our own group, for founders only. No one else can come in, because we’re naïve, we’re pathetic, but we also have a lot of potential. That was the impetus for Starve Ups.”

Starve Ups held its first meeting on Oct. 15, 2000, with founding companies Wired.MD, Rumblefish, Asset Exchange, viaLanguage, GC Materials, Versation and CoolerEmail. Friess argues that the results of these and other Starve Up companies over the past decade prove that peer-to-peer mentoring works. “Seven of our original eight members kept going with the group,” says Friess. “Two have been acquired. All are profitable. Some are extremely profitable. And we’ve added 47 members total over the years; 40 of those 47 are still in business. Over two-thirds are profitable. We think that by the end of next year we’ll be close to 15% getting acquired and by the following year we’ll be at 20%.”

Friess also credits the Starve Ups’ model for his own successful exit. He estimates that more than 130 people made money when Wired.MD was acquired by Krames (a division of MediMedia) for $7.5 million in January 2008. “We sold the company for about two-and-a-half times the amount of money we had raised,” he says.

That payout has enabled Friess to move onto his next business, Journey Gym, a mobile gym for fitness-conscious travelers. Journey Gym is a member of Starve Ups along with Jive Software, Plas2fuel, Keen Footwear, Khanna’s MergerTech and other promising companies.

Friess is particularly jazzed about MergerTech’s membership in the group because of Khanna’s expertise in building up a company and cashing in ambitiously. “It’s all about the acquisition now,” says Friess. “With Nitin’s help, we want to get 25% of our member companies to acquisition if exit is the plan.”

If that plan comes to fruition, it could spawn a related fund that would be similar to the Portland Seed Fund, but open exclusively to Starve Ups companies. Friess says members have been planning to create a fund for years, to vote on investments and require that all companies that earn investments must join the group to make the most of the peer-to-peer mentoring. Member companies would pay back into the fund as they sell their companies, continuing the cycle.

Friess believes that such a fund would complement the city’s seed fund rather than compete with it.

“I don’t think there would be any competition between a Starve Ups fund and the fund Josh wants to start,” he says. “We need 20 more of them. The more funds we can start in Portland, the better. The more money we can bring into the state, the better. The more entrepreneurs we can spawn, the better.”