A market slump. Competition from China. Geopolitical unrest. Tamara Lundgren tackles the challenges — without getting trampled.

On a late September evening, about 25 women, many financial officers and managers of Oregon companies, gathered on the fourth floor of the Portland Art Museum for a dinner and networking event hosted by Wells Fargo. Tamara Lundgren, president and CEO of Schnitzer Steel, was the featured speaker. During her 20-minute speech, Lundgren, elegant in a black cape dress, talked about what it was like to take the reins of the 109-year-old-company in 2008, months before the global financial crisis hit.

“It was like I moved into the house of my dreams only to find the floor had collapsed,” she said. But despite the challenges, leading the Schnitzer team through turbulent times was a privilege. “When you’re getting battered by outside factors, it really creates a sense of common purpose, and enables people to focus on what’s important and rise to their best.”

In her ten years with Schnitzer, one of the country’s largest steel and scrap metal producers, Lundgren, 57, has steered the company through several economic crises and, today, still faces a trifecta of challenges: a market slump, growing competition and an ever-shifting geopolitical landscape.

But Lundgren, who in addition to running a $2.6 billion company, serves on the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and this year became chair of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, is not waiting for the world markets to turn around.

“I’m very rewarded when we can grow a company, but I’m also very rewarded when we can impact our own results even in a tough environment,” says Lundgren, who met me in August in the company’s KOIN Tower headquarters. “There are a lot of things we are able to do to drive our own destiny.”

“I’m very rewarded when we can grow a company, but I’m also very rewarded when we can impact our own results even in a tough environment,” says Lundgren, who met me in August in the company’s KOIN Tower headquarters. “There are a lot of things we are able to do to drive our own destiny.”

Navigating the global steel industry

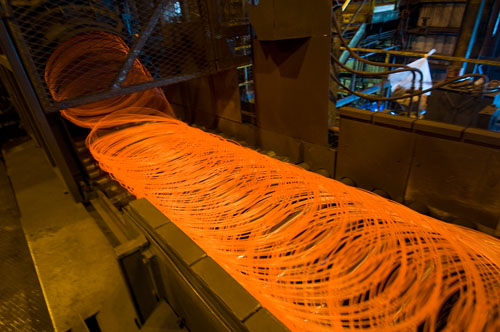

An archetypal industry associated in this country with immigrant peddlers — including one Sam Schnitzer, a Russian immigrant who started the company as a one-man scrap business in 1906 — the metals recycling business burst onto the global radar about 10 years ago, as developing countries began to modernize. As Lundgren points out, in an emerging economy, steel is one of the first industries to get established. Most of the steel in the world is made by melting down scrap metal, and since developing countries don’t have enough scrap to feed the steel machine, they depend on developed countries like the U.S. to supply the raw material.

“It’s that supply-demand imbalance that is in favor of consumer-driven economies that generate the scrap we export,” Lundgren says.

That cycle was in full swing in 2004. “Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Middle East — there wasn’t a country that wasn’t investing in infrastructure, energy, roads and bridges,” Lundgren says. “All of that requires steel.”

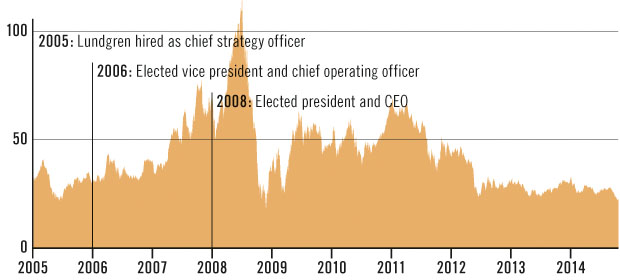

Then the financial crisis hit. Demand plummeted in 2009. Schnitzer lost almost half its revenue, and its share price dropped from a peak of $118 in the summer of 2008 to $16.45. A strong recovery followed as developing countries continued to grow. But the 2011 European crisis took a different path, Lundgren says. “That’s when emerging markets started a decrease in their growth trajectory.”

The result has been “turmoil in the industry and a lot of excess capacity,” says Brent Thielman, an analyst who follows the steel and scrap markets for D.A. Davidson in Lake Oswego. Thielman points to signs of a “slowly” recovering market, fueled by an uptick in commercial construction. “But there is more competition than existed 10 years ago. Slow is the word.”

At Schnitzer, business has improved since 2009. But profitability is a challenge and the stock price, now around $22, has remained flat for the past few years.

Lundgren, who made $3.4 million in total compensation in 2013, is unfazed. “I’m focused on things we can control,” she says.

A laser focus on strategy, away from the media spotlight

At 5-foot-2, the auburn-haired Lundgren is noticeably petite, with a conservative sartorial style — black pantsuit, heavy gold jewelry — and a down-to-earth but firm demeanor. Despite her high powered board and executive positions, Lundgren is surprisingly media-shy and guards her personal life closely — although she bristles at the suggestion she keeps a low civic profile in Oregon, where the company employs 800 people. “I view myself as very active in public policy, not only in Oregon but across the country and around the world.” Lundgren points to Schnitzer’s many charitable activities — including the Oregon Food Bank and a new nonprofit foundation, Race Against Hunger. John Carter, Schnitzer Steel’s board chair, is the chair of the Oregon Business Plan.

{pullquote}I’m very rewarded when we can impact our own results even in a tough environment.{/pullquote}

As the only female CEO of an Oregon public company, Lundgren occupies a unique position in the state’s business pantheon. But she doesn’t dwell on gender, and when the issue does, inevitably, come up, she prefers to steer the conversation toward “creating equal opportunities for everyone.” It’s a simultaneously pragmatic and big picture approach that seems to characterize her executive leadership at Schnitzer, a commodity business that employs 3,371 workers at 120 facilities in the United States, Canada and Puerto Rico. These include metals manufacturing and recycling facilities, as well as a network of used auto-parts junkyards.

It’s a gritty industry and a far cry from the hallowed halls of law and high finance, where Lundgren spent much of her career. After receiving a law degree from the Northwestern School of Law in 1982, she worked in private practice before moving on to Goldman Sachs as the investment-banking boom took off. She lived in New York and then London for a decade, helping shape the emerging field of securitization as a manager of Deutsche Bank.

In 2005, Lundgren was approached by Carter, a longtime colleague and former Bechtel executive who had come out of retirement to lead Schnitzer and was searching for strategy officer. In 2006, Lundgren was elected chief operating officer and in 2008 became CEO.

Six years later, Schnitzer’s board, which awarded Lundgren a $615,000 bonus in 2013, heaps praise on her performance. “The reality is that it is a tough global marketplace, and economies are not expanding or growing at the rate they were 10 years ago,” Carter says. Since joining Schnitzer, Lundgren has implemented a company-wide cost-cutting and “productivity” program, he says, and “has done a terrific job impressing on management that these are tools that [impact] how you stack up against competitors.”

Making an old industry new

To understand Lundgren’s strategy for boosting profitability and growing volumes — “my actions are all driven toward those two goals” — start with the fact that Schnitzer’s vertically integrated operations mirror in many ways the global scrap-steel dynamic. The company’s steel mill in McMinnville makes steel products for buildings and infrastructure. A metals recycling division buys “end of life” vehicles, manufacturing waste and demolition materials, then processes and sells the materials to 20 countries around the world. Operating under the brand Pick-n-Pull, the auto-parts business consists of 62 self-service auto yards, where customers can pry off hubs, fenders, trims and other parts.

“When the car has been in inventory long enough, we take it off the lot, crush it,” Lundgren says. “Then it goes to the recycling division, shreds it, and it goes to steel making. The steel in the car turns into steel used to build one of the bridges or a high rise.”

“When the car has been in inventory long enough, we take it off the lot, crush it,” Lundgren says. “Then it goes to the recycling division, shreds it, and it goes to steel making. The steel in the car turns into steel used to build one of the bridges or a high rise.”

Lundgren has focused on making this cycle more efficient; she is also positioning Schnitzer to capitalize on 21st-century social, economic and technology trends. In 2013, for example, the company expanded its Pick-n-Pull network by 20%, with most of the new sites located near its metals recycling operations as well as a network of seven deep water ports the company either owns or has exclusive rights to. The goal, Lundgren says, is to drive synergies between the business divisions. Likewise, Schnitzer has also invested in advanced technologies that extract smaller and smaller pieces of metal “so less goes to the landfill, more gets recycled and we have more to sell.”

Steel, Lundgren likes to say, is the most recycled material in the world. She touts the company as a sustainability leader — “we’ve been about sustainability before that was cool, before it was probably a word” — in an era when being green has cachet not just for consumers but sustainability investors as well. “That’s what’s been fun,” Lundgren says. “Making this very old industry and company relevant to the world today.”

A foray into the sharing economy qualifies as another example. Last year Schnitzer launched an online marketplace called Row52 featuring pictures of the Pick-n-Pull inventory, as well as cars from other yards — around 115,000 vehicles. The site has created a new crop of micro-entrepreneurs called “Parts Pullers” who register with Schnitzer, buy parts and sell them at a mark-up to people around the country.

“I love creating jobs; it’s a real driver for me,” says Lundgren, who credits her father, a pediatrician, and her mother, a former homemaker turned stock broker, with raising her with the expectation she would contribute to the community. “My way of giving back seems to be that I always gravitated toward a platform that has growth potential,” she says. “I have never been attracted to caretaking businesses.”

Schnitzer has made several rounds of layoffs since the 2008 and 2011 financial crises, including a 7% reduction in the workforce last year.

Echoing Lundgren’s self-assessment, her colleagues describe her as an intensely focused and strategic leader — who has created a corporate culture in her own image. “Tamara has a strong vision for the company and is always raising the bar in terms of what I and the business should be able to achieve,” says CFO Richard Peach. But she is also “keen to receive ideas,” Peach says. He recalls his first conversation with Lundgren in 2007, when she interviewed him for his position. “She said she was interested in a cultural change in finance and wondered if I was sort of person who could be her partner and lead that change. I was really taken by her enthusiasm and creative thinking. It’s a big reason I came to the company.”

Of her own leadership style, Lundgren says she encourages discussion and debate, following the advice of a former boss, who once told her: “’If I can convince you of my perspective, I get results. But if you can convince me of your perspective, I’ve learned something, so I win too.’” An avid golfer and all around sports fan, Lundgren invokes a football metaphor: “I like to play left offensive tackle. I look for where any one of my team members is going to get tackled and not going to see it coming.”

Steel diplomacy

While working at Deutsche Bank, Lundgren often had to explain complex, jargon-filled topics like structured finance to people who weren’t proficient in English. It was a task she relished. “In the U.S. you don’t get to exercise that muscle,” she says. “You get addicted to the challenge.”

Today she flexes that muscle on business trips to Europe and Asia, where developing countries that once drove the demand-supply imbalance are now evolving into consumer economies, complicating the dynamic. Once the major source of demand, China is now the world’s largest producer of steel — and the target of a large number of trade cases filed by U.S. companies concerned about the country dumping steel in the U.S. at unfair prices.

In September the U.S. Commerce Department imposed preliminary duties on Chinese wire rod, a steel product used in chain link fencing and nails. The action may limit imports going forward, says Lundgren, who recently returned from a trade mission to China. There she met with Premier Li “about the issue of overcapacity in the market.”

China is undergoing seismic shifts in the social, political and environmental spheres, Lundgren says. “What can accelerate recovery of steel is to reduce oversupply. [China] is the trickiest piece right now.” On that same trip, Lundgren met with President Park in South Korea, also the target of U.S. anti-dumping cases. There are other international issues on her radar, including unrest in the Middle East and the Ukraine. “Political instability overall affects economic growth.”

Ask Lundgren what excites her about being the CEO of a global metals recycling company and she’ll say, among other things, that she likes working in an industry that is a barometer for social, economic and political change.

“We are driven by macroeconomic events and microeconomic events,” she says. “That includes a lot of little things, like whether you are holding on to your washing machine, because that impacts GDP growth. A huge amount of our material is also exported internationally, so what’s going on in the Mideast, in Europe, in Asia, is relevant. Waking up every morning and reading the paper is what’s exciting about my job.”

Lundgren’s board commitments reflect her deep interest in national and international affairs. They also give her a platform to champion issues that impact Schnitzer’s bottom line She serves on the board of Ryder System, a Florida-based truck leasing and maintenance company, and as chair of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce — a business group known for its conservative free market political positions — she has made infrastructure one of her top three priorities. The other two are immigration and environmental stewardship.

{pullquote}I like to play left offensive tackle. I look for where any one of my team members is going to get tackled and not going to see it coming.{/pullquote}

Last summer, Lundgren co-chaired a conference on infrastructure with Representative Earl Blumenauer at Portland State University. Lamenting the state of Oregon’s bridges — over 400 are deemed structurally deficient — she called for a new era of public private partnerships to solve the problem. “You don’t need to jack up taxes; you don’t have to overleverage federal funds.”

Then there is her work with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco — “the most interesting thing I’ve done in my life.” Hers is a grueling schedule, to be sure, made more complicated by a bicoastal marriage. Lundgren’s husband, John Lundgren, whom she met in London, lives in Connecticut, where he is CEO of Stanley Black & Decker, the power tools and household hardware company. Tamara maintains a residence in Portland, and the couple meets up every weekend: in Connecticut, in Boston, in California. “Her energy level makes my hectic schedule look, on occasion, like summer vacation,” John Lundgren said in an email. “But she still gets everything done.”

Asked by a guest at the Wells Fargo dinner how she does it all, Lundgren laughed: “I don’t have kids. I don’t have cats.”

Today there is talk of a nascent global recovery, including an increase in construction activity on the West Coast and a building boom in Turkey, one of the top destinations for Schnitzer ferrous metals this year.

Today there is talk of a nascent global recovery, including an increase in construction activity on the West Coast and a building boom in Turkey, one of the top destinations for Schnitzer ferrous metals this year.

These are among the reasons Lundgren is optimistic about Schnitzer’s growth potential. She ticks off the numbers. The steel mill is currently operating at 72% of capacity, a far cry from 100% in 2008, but up from 50%, where it fell in the recession. Scrap volumes are running slightly more than 4 million tons, up from 3 million in 2008, but down from 5 million in 2011. Looking ahead, Lundgren wants to exceed 2011 scrap levels and double the auto-parts business.

“U.S. steel manufacturing is going up, and so demand for scrap is going up. That corresponds to job growth. That means people start buying more cars, and end-of-life vehicles start flowing into Pick-n-Pull. It’s a virtuous cycle.”

So is driving your own destiny. In its fourth quarter earnings preview, announced on September 30, Schnitzer forecast the highest quarterly operating income for the steel business since 2008 — largely because of the productivity improvements, which include energy conservation upgrades and enhanced capacity to ship by rail. In 2014, these initiatives have realized $20 million in savings. Lundgren is equally proud of the company’s safety record, which since the downturn continues to improve year over year based on metrics the company tracks.

When I met Lundgren in her office in late August, she said she had spent most of the previous week in investor meetings. Minor gloating was apparently part of the agenda. “Every CEO says: ‘We’ve got productivity initiatives and they’re going to deliver results,’” Lundgren said. “I said: ‘Ours are delivering results, and I’m going to tell you about them.’”

Sidebar: Gender neutral

Tamara Lundgren doesn’t dwell on her status as a female CEO in a male-dominated industry. “Every industry I’ve been in has been male dominated when I’ve been in it,” she says. “My law school class was 20% women; now it’s over 50%. I was one of the few women on the trading floor in London, and now the numbers are really different. So I see it evolving. These things take time.”

Lundgren does say more formal and informal mentoring opportunities would help women attain C-Suite and corporate board positions.

She also advocates applying “the Rooney rule” to gender diversity. In 2003, at the instigation of the Pittsburgh Steelers’ owner, Dan Rooney, the NFL agreed that any time a team was searching for a coach or general manager, they had to make sure their interview pool included minority candidates. “I’d like to see every organization use a version of the Rooney rule. Why not insist every interview pool includes people of both genders?”

Sidebar: Downtime with Tamara Lundgren

“I read a lot about politics. I just finished reading Robert Gates’ book, Duty, Memoirs of a Secretary at War, when I flew out to Asia. I’m a big fan of Doris Kearns Goodwin. I met her at a small dinner, and she is a fascinating woman. She is one of the few people I know who speaks in paragraphs.”

“I used to sit on the board of the James Beard Foundation. I’m an adventurous eater and wish I were a really good cook.”

John Lundgren on Tamara: “Shortly after our first date, when a mutual friend asked how it went: I said: ‘I really liked her – especially when I realized it was one part dinner, two parts deposition. This is way to capture her intellectual curiosity and a genuine interest in people.”

Tamara Lundgren on John: “We joke we’re hedged. When steel prices are high, I’m happy. He’s just the opposite.” John is the CEO of Stanley Black & Decker, a Connecticut-based company that makes power tools and household hardware.

A version of this article appears in the November/December issue of Oregon Business