Boosted by new state incentives and betting on the future, Oregon’s solar industry is soaring.

SUN, SUN, SUN, HERE IT COMES

SUN, SUN, SUN, HERE IT COMES

Boosted by new state incentives and betting on the future, Oregon’s solar industry is soaring.

By Ben Jacklet

John Schumacher developed a revolutionary idea to lower the cost of solar power during the last oil crisis 33 years ago. Answering a call from the U.S. government for solar innovations, he invented a closed-loop, low-energy system to produce high-quality polysilicon for solar cells. He was certain his process would improve efficiency throughout the solar industry, but he never got to find out. Support from the government faded as oil prices returned to earth, and investors didn’t fill the gap. Schumacher reluctantly dropped his plans and proceeded with a successful career that saw him earn over 40 patents and create hundreds of high-paying R&D jobs through the various technology companies he created in California.

Three decades later, Schumacher is getting another chance to make his solar system a reality — in Oregon. His company, Peak Sun Silicon, has broken ground on a polysilicon manufacturing plant in Millersburg, north of Albany, with ambitious plans to raise $718 million and create 500 jobs by the end of 2011, generating raw materials for a solar manufacturing industry that is growing robustly both globally and in Oregon. State officials predict that by this time next year Oregon will reach $1.4 billion in committed capital for solar manufacturing. And that figure doesn’t include the earnings of a growing legion of system installers, distributors, marketers, electricians, researchers, financial consultants, lawyers and architects who plan to be soaking up rays and revenues as the push to solar intensifies.

|

Oregon is betting big on all forms of renewable energy, but none has drawn more investment and business interest than the burgeoning solar industry. At the world’s largest solar trade show in Munich, Germany, in April there was one U.S. state with its own booth: Oregon. Solar entrepreneurs enticed by lucrative incentives, most notably the German powerhouse SolarWorld, are pouring into the Oregon market, and more are being recruited, making the state’s goal of a “self-reinforcing cluster” in the solar industry seem less like wishful thinking and more like concrete reality. Residential solar installations are up 35%, commercial projects are on track to quadruple from 2007 to 2008, and the market looks even sunnier to the south, where California has launched a $3.35 billion solar initiative that will further boost demand for solar equipment that is more and more likely to be made in Oregon.

The timing is serendipitous. The weak dollar is boosting exports and sending oil prices to all-time highs. New concerns and laws regarding climate change are strengthening a market that is firmly established in Europe and growing everywhere else. Venture capital investments in solar energy topped $1 billion in the U.S. last year, and two of the hottest stocks on Wall Street have been First Solar in Phoenix and Sun Power in San Jose. With a strong Silicon Forest workforce familiar with the basic technology used in solar manufacturing and some of the most generous subsidies offered by any state, Oregon has positioned itself to capitalize mightily on what New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman recently labeled “the next great global industry — clean power.”

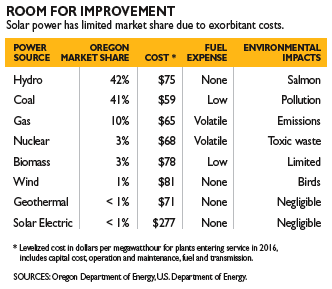

But for all of the investor exuberance regarding solar, the fact remains that solar energy is not even close to eclipsing wind power, much less coal, hydro and even nuclear energy. For solar to compete without exorbitant subsidies, costs must come down. That is the goal of the solar companies expanding in Oregon, and the industry as a whole.

Joseph Reinhart, executive director of the Oregon Solar Energy Industry Association, says solar’s future is rooted not in idealism but in “continued and sustained profitability.” A veteran of the semiconductor industry, Reinhart doesn’t see any reason why mass production and innovation can’t bring down costs quickly. “Just think about the $800 laptop you can buy today,” he says. “Less than 10 years ago it was $2,500, and you can’t even compare the functionality. I see the same thing happening with solar.”

|

For the past 30 years Oregon’s solar sector has been dominated by early adopters with plenty of ideas and innovation but limited access to capital. That has changed dramatically. According to the Portland-based research firm Clean Edge, capital investment in renewable energy companies in the United States has ballooned from $599 million in 2000 to $2.7 billion in 2007. VC investment in solar topped $1 billion in the nation in more than 700 financing rounds last year, according to the Prometheus Institute, a sustainable technology research firm based in Cambridge, Mass. Global powerhouses such as General Electric, Google and Applied Materials also are wagering aggressively on the future of solar as a hedge against rising energy prices and concerns about the true costs of pollution and climate change.

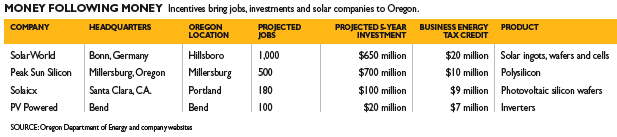

Oregon saw the light in the legislative session of 2007, approving sizable subsidies to companies willing to invest in solar. The biggest incentive is an aggressive business energy tax credit or BETC (pronounced “Betsy”) that was expanded by the state Legislature in January to cover an enticing 50% of a company’s investments up to $40 million. This super-sized incentive has had an immediate impact, enabling companies to leverage significant capital to set up, expand and drive up production in Oregon. Four companies — SolarWorld, Peak Sun Silicon, Solaicx and PV Powered — have received state approval for a combined $46 million in tax credits from this one subsidy alone.

A little more than a year ago, PV Powered was a small startup in Bend with 25 employees building inverters to change the direct current generated by solar systems to alternating current compatible with the grid. Now, with the help of $7 million in BETCs and nearly $30 million in venture capital, the company has grown to more than 60 jobs at a new 100,000-square-foot facility and plans to keep growing in Bend and begin exporting.

|

Gregg Patterson, a former Hewlett Packard vice president and general manager, took over as CEO and chairman of PV Powered in March 2007. His eyes grow wide as he describes market potential. “The worst forecast I’ve seen calls for a 30% annual growth rate for solar,” he says. “And the inverter will be a critical component of every installation.”

Solar experts have long decried the inverter as a weak link in the photovoltaic chain, causing 80% of a system’s downtime. Like all inverter manufacturers, PV Powered has struggled with reliability. But a recent collaboration with Boeing has helped the company tighten quality control standards; its inverters come with a 10-year warranty.

The more efficient a system becomes, the better it will compete. That is one of many lessons Jeff Jones learned from the boom years of the semiconductor industry. Jones was one of the original hires when Siltronic moved to Portland in the late 1970s, and in his 28-year career there he trained 450 people to manufacture semiconductors. Now he’s doing the same thing with silicon wafers for solar cells.

Jones left Siltronic during a recent downturn and is now vice president of manufacturing at the new Solaicx manufacturing plant in North Portland, where the sign on the entrance states the company’s mission clearly: “Making Solar Electricity Cost Effective.” Jones compares the solar market to the market for semiconductors in the early ’80s. “It seems like every time you turn around someone has figured out something they were never able to figure out before.”

Jones left Siltronic during a recent downturn and is now vice president of manufacturing at the new Solaicx manufacturing plant in North Portland, where the sign on the entrance states the company’s mission clearly: “Making Solar Electricity Cost Effective.” Jones compares the solar market to the market for semiconductors in the early ’80s. “It seems like every time you turn around someone has figured out something they were never able to figure out before.”

Solaicx designed and built the machines at the center of its new Portland factory. The company developed its high-volume process over five years of research in California backed by $58.4 million from investors and expanded to Portland in 2007 after considering Austin, Phoenix and Vancouver, Wash. Among the many government incentives that enticed Solaicx to Portland was a BETC worth approximately $9 million.

Solaicx CEO Bob Ford says government support played a role in the decision to set up in Portland, but the region’s reliable, low-cost power was also a factor, as was the available workforce. “There were five crystal-growing operations already here and some of them were closing down,” he says. “That means you have an immediately available pool of workers who understand the process.”

The company has hired more than 50 people and is accepting applications for crystal growers and wire saw operators. Ford predicts the number of jobs will double by the end of the year as the company works out the kinks in its new process and gears up to meet demand. “The solar industry is a locomotive that has already left the station,” he proclaims, “and it is accelerating.”

|

Solaicx and PV Powered are growing quickly and may one day raise further capital by going public. But for now their combined market share is minuscule compared to that of SolarWorld, the vertically integrated German giant that is building the nation’s largest solar factory plant in Hillsboro.

SolarWorld vice president Bob Beisner says his company considered the option of building in Asia to save on labor costs and rejected it. “We made a decision to manufacture in the U.S. because we feel the U.S. will become one of the biggest marketplaces for solar in the world over the next five to 10 years. For us to be here makes perfect sense. It will help us to diversify our risks, and the euro exchange rate makes it very favorable to be manufacturing in the U.S. We were also dissuaded by intellectual property rights laws in China.”

Beisner says SolarWorld chose Oregon over states such as California, Washington and Colorado because the Silicon Forest “gives us an automatic base of people, vendors and suppliers that already understand silicon. We can go out and get crystal, we can go out and get graphite, we can go out and get the people to maintain our equipment because our equipment is very similar to what is used in the semiconductor industry.”

Local and state subsidies also played a role, including an enterprise zone property tax abatement, $500,000 for workforce training from the state’s Strategic Reserve Fund and a whopping $20 million BETC. SolarWorld plans to create 1,000 jobs by 2010 and may expand beyond that depending on the market.

SolarWorld’s stock peaked last November but has returned to earth as solar panel prices have gone up instead of down. The mass production that was supposed to bring down costs in the industry has created a global shortage of silicon, and prices for that crucial material have risen from $25 to $400 per kilogram, making it even more of a challenge to bring down prices.

But the silicon shortage is expected to be short-lived, as new companies such as Peak Sun Silicon rush to meet demand. Peak Sun CEO John Schumacher has launched the first of three planned phases for the Millersburg plant, backed by undisclosed private capital and a healthy package of subsidies including a seven-year property tax abatement and a $10 million BETC.

Schumacher has a strong record of turning ideas into profits for the J.C. Schumacher Company and other enterprises, but he has yet to prove that his manufacturing system can reliably produce large volumes of cost-competitive, high-grade polysilicon. Assuming he succeeds, he will have no shortage of customers, including SolarWorld and Solaicx, which will need a steady supply of polysilicon for their processes. Schumacher predicts other solar companies will move to Oregon because of the availability of silicon, not to mention the strong support from state officials.

Christopher Dymond, the solar program manager for the Oregon Department of Energy (ODOE), says landing SolarWorld and Peak Sun makes it easier to convince businesses that Oregon is serious about solar. “When I talk with other companies, they ask ‘Well, what do you have there already?’ It’s a question that comes early in the conversation.”

Tim McCabe, newly appointed director of the Oregon Economic and Community Development Department, says the state is recruiting 11 solar manufacturing companies from the Munich trade show, five of which have already visited Oregon. “We’re trying to capitalize on this because it won’t last forever,” he says. “More states are offering incentives and the competition will get tougher.”

Oregon recently lost out in the battle to recruit Schott Solar, which plans to invest $500 million and create 1,500 jobs in Albuquerque, N.M. as a result of an aggressive package of incentives from New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson. Other states have outbid Oregon to attract an estimated $4 billion in investments from Schuco International, Evergreen Solar, Optisolar and REC, according to an ODOE report.

Large manufacturers aren’t the only Oregon businesses investing in subsidized solar. Kettle Foods, Pacific Botanicals, PepsiCo, Gerding Edlen and Sokol Blosser Winery are just a few of the companies that have installed solar systems on their rooftops with support from the Energy Trust of Oregon.

Kacia Brockman, the trust’s senior solar program manager, says incentives can make solar installations attractive, with a return of up to 8% over the life of the investment. “It’s not a huge moneymaker, but it is a sound investment,” she says. “And it’s very low risk, because the systems are guaranteed to produce power for 20 years.”

|

The more systems that are installed, the more demand there is for workers with solar expertise. In 2003 the trust had 12 “trade allies” to collaborate on solar installations. That number has grown to more than 100, according to Brockman. The trust also has helped train more than 750 union electricians to assist with solar installations.

There is also more work than ever for renewable energy specialists from law firms such as Stoel Rives and Ater Wynne, research firms such as Clean Edge, developers such as Commercial Solar Ventures, plus the growing legion of distributors and marketers moving into Oregon. The nation’s first renewable energy undergraduate degree at the Oregon Institute of Technology should bring more expertise into the industry, as will training programs through Portland Community College and research efforts at the University of Oregon and Oregon State University. New products ranging from solar-powered skylights and scooters to the City of Portland’s goofy solar-powered garbage cans are just the beginning. The next big thing will probably be building materials with solar cells incorporated into them.

According to University of Oregon physics professor Frank Vignola, two thirds of Oregon receives more solar radiation than does Florida, and even soggy Astoria gets more sunlight than Germany, which leads the world in solar installations. The state’s recently enacted environmental goals — to achieve 25% of power from renewable sources by 2025, limit carbon emissions below Kyoto Protocol levels and put 1.5% of costs for new public buildings toward solar — virtually guarantee that all new energy investments will be in clean power. But the same low energy costs that have enticed large solar manufacturers to move to Oregon also make it impossible for solar to compete with local power rates. As one developer admitted at a recent energy forum, “The main thing the incentives do is to keep a company’s CPA from laughing at you.”

Nonetheless, solar installations are heating up as businesses, governments and nonprofits strive to highlight their green credentials. Last month workers began installing panels for a 870-kilowatt system on the rooftop of the Portland Habilitation Center near the PDX airport. The project’s developers billed it the largest solar installation in Oregon, but it won’t be for long. Larger plans are in the works from Multnomah County to Arlington to Medford. Portland General Electric, which boasts more customers willing to pay a premium for renewable power than any other utility in the nation, is seeking up to 218 megawatts of additional renewable power sources, and the utility has set the project threshold low to encourage solar proposals.

PGE and the Energy Trust of Oregon are also working with ProLogis, the largest owner of warehouses in the world, to convert 17 Portland-area roofs into the equivalent of a 3.4-megawatt solar power plant. “So far we’ve done about 750 rooftops in Oregon,” says Peter West, the trust’s director of renewable energy. “Just think about all the roofs in Oregon. We’ve barely touched the possibilities.”

That’s a common theme throughout the industry. For all of the renewed excitement about solar energy, it holds less than one-tenth of 1% of the world’s energy market. The possibilities for growth and innovation seem endless, but it remains to be seen whether the industry will succeed where it failed during the previous oil crisis in lowering costs to compete without subsidies. Eventually, it will come down to results. Until then, Oregon’s new crop of solar innovators will be humming along to meet demand, scrambling to prove that the state’s incentives have been money well spent.

Schumacher is confident that the red-hot market for solar is no passing phase this time, and the main reason behind that is money. “Nobody ever made any money in this business before now,” he says. “Now the timing is right,” says Schumacher. “There is money to be made. People are willing to invest and take risks because they see there is no other way out. We have to get rid of our oil dependence. There’s no other way. It’s got to be done.”

To comment, email [email protected].