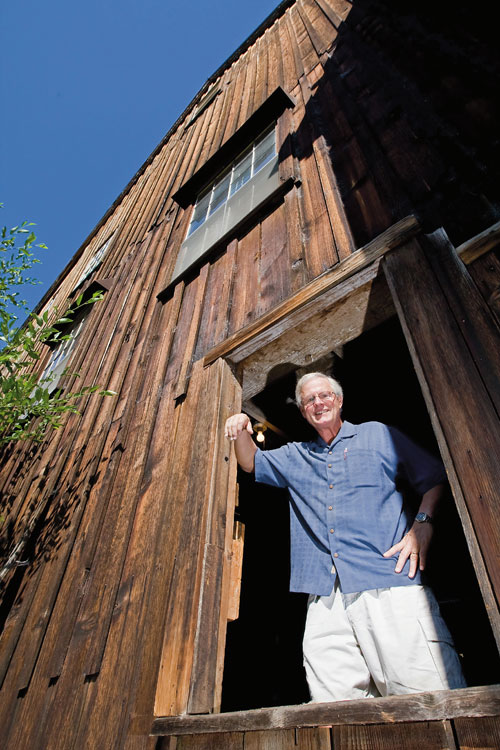

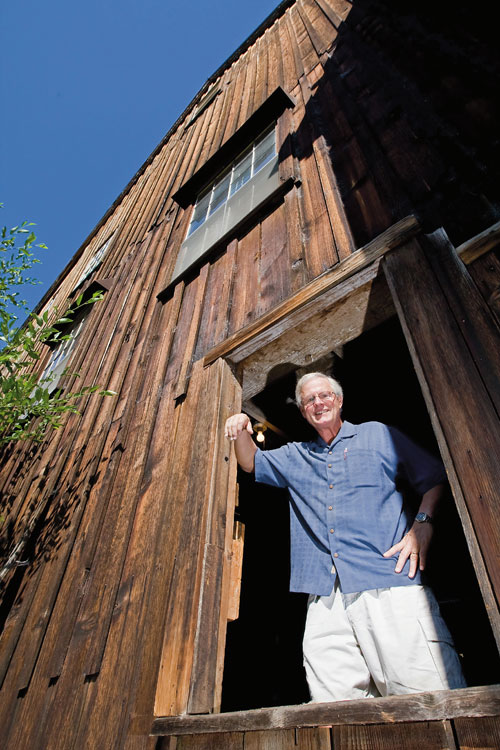

Bob Russell finds his dream in making Butte Creek Mill a thriving business for Eagle Point.

Bob Russell finds his dream in making Butte Creek Mill a thriving business for Eagle Point.

Bob Russell finds his dream in making Butte Creek Mill a thriving business for Eagle Point.

BY JENNIFER MARGULIS // PHOTOS BY JAMIE LUSCH

|

Bob Russell bought Oregon’s only water-powered grist mill in 2004 for $595,000. It’s turned into a thriving draw for tourists in Eagle Point. |

Bob Russell, a tall man with an affable smile, likes nothing better than to show visitors around the historic landmark he has owned and operated for the past four years: Eagle Point’s Butte Creek Mill, Oregon’s only water-powered grist mill that has been in continuous operation since the 19th century.

Display cases in the vestibule show black-and-white mill photos from 1883 with farmers waiting with their grain in long lines of horse-drawn wagons. There are also antiques and Native American artifacts, including an old Indian mortar and pestle unearthed near Little Butte Creek that supplies the water to run the mill.

Past this is the heart of Russell’s operation: the grinding room. Here some 150,000 pounds of wheat berries, corn, and other grains are ground into flour to produce approximately 300,000 pounds of product (with other added ingredients) annually. Here the air is sweet with the smell of wheat and corn, like in a bakery. And it’s surprisingly noisy as the belts and the 137-year-old French Buhr grinding stones turn at about 100 rotations per minute. Everything moves fast as freshly ground corn shoots into a sifter while flour jets into a 25-pound bag. There are crisscrossing metal tubes, a grain elevator and myriad ropes dangling from the ceiling.

The clatter and chaos do not faze the 59-year-old Russell, who explains that grain berries are stored in huge ceiling bins and ropes are pulled depending on what grain is being ground. Making a major life change didn’t seem to faze Russell either. Though he says he had never considered owning a business, when he first saw the mill on an overcast day in 2004 while visiting the area with his wife, Debbie, he knew he had to buy it.

Russell calls the purchase “a screaming good deal.” He sold some of his antique collection and his home in Lake Oswego to pay $595,000 in cash for the business and surrounding 2.7 acres that has 810 feet of frontage onto Little Butte Creek.

“I don’t think we could’ve gotten a bank to finance it,” Russell admits, explaining that the safety hazards and structural problems with the mill were so serious when he bought it from Peter Crandall that he was sure a bank would have turned him down. He put an additional $200,000 in cash into upgrading the property, which Crandall had owned since 1972.

A self-described “city boy” who grew up in Portland, Russell graduated from Oregon State University in 1972 with a B.S. in business. Then Russell says he “went to the school of hard knocks in the copier world,” where he worked his way up at Savin, a company in competition with Xerox, to become the company’s sales manager who oversaw new hires. After eight years at Savin, Russell landed a sales position at Canon USA, where he worked for 13 years, becoming district sales manager responsible for Washington, Oregon, Hawaii, and Alaska, depending on the year. He excelled in his job and was recognized as the company’s top performer in the United States six times.

But Russell, who has three grown children, had no hesitation about leaving what he calls “the suit-and-tie world” after 25 years. Antiques have been a lifelong passion and restoring the mill was something Russell tackled with characteristic energy and enthusiasm.

It took three months of sweat equity to clear the creek frontage, which was so overgrown with blackberry bushes, weeds, wrecked cars and broken refrigerators that the water wasn’t visible. Russell also had to remove an ammonium-fed refrigeration system that had long posed an environmental hazard to the creek, and install a packaging facility so a larger volume of product could be shipped.

He bought and renovated the 1911 Craftsman across the street to live in and also opened an antiques store in the adjacent building, which was once the Ladino Cheese Factory. The shop has embossed tin ceilings and Douglas fir tongue-and-groove floors and is crammed with curiosities: a teapot shaped like a camel with an African rider on the lid, a glass butter churn with metal paddles and a steam-powered peanut roasting machine from 1880.

“I love to take basket-case projects and make them into something,” says Russell as he points out antiques he has painstakingly renovated. This has been a lifelong interest: at 11 years old, he found an 8-foot-tall barber pole in an abandoned building on Union Avenue in Portland, which his father helped him haul home in the family station wagon. This first valuable antique, is kept in the upstairs bathroom of his home. Over the years he’s become such a packrat that he and Debbie drove 17 rental truckloads of stuff over a five-month period when they moved.

In addition to repairing the mill, Russell found himself facing the task of rejuvenating a failing business. The mill had never had a website or anything more than a tri-fold black-and-white brochure. Russell built a website, joined the chamber of commerce, began networking among local businesses, developed a detailed color brochure to explain the mill’s history, which he continues to research, and created a historical DVD that plays on a loop for visitors. He also implemented an outreach program for local school children, who visit the mill to observe how it operates and learn about nutrition and gardening (they plant wheat in the spring and come back in the fall to harvest it), and he started developing personal relationships with customers. It’s a good bet that seven days out of seven you’ll find Russell at the mill.

|

|

|

The mill is a big draw for history buffs and cultural tourists, and also visitors interested in the growing Southern Oregon food and wine scene. In 2008, Butte Creek Mill produced more than 250,000 pounds of grain product. |

Russell’s aesthetic sense, understanding of history and value of community extend beyond the mill. Two years ago he began an Eagle Point revitalization project, which involved installing flower baskets all over town. While the city pitched in to finance this effort the first year, Eagle Point mayor Leon Sherman, who has lived in the town since 1965, says it is now funded entirely by business donations. “Mr. Russell is solely responsible for that program,” says Sherman, who laughingly adds that he has tried to convince Russell to run for mayor. “Mr. Russell immediately became a part of our community, he just jumped right in.”

Because of Russell’s efforts, more tourists than ever have been visiting Eagle Point. “Since Bob has taken over, more people are coming to the mill as a destination; it’s been truly amazing,” says Anne Jenkins, senior vice president of the Medford Visitors and Convention Bureau.

“The mill is a key attraction to our area,” agrees Jackson County Commissioner C.W. Smith, an Eagle Point resident who met Russell when the entrepreneur first moved to Southern Oregon from Portland. Located just north of Medford, Eagle Point has a population of about 9,000 inhabitants and is considered a bedroom community for the bustling city of Medford. “Bob has brought a new energy and a very entrepreneurial spirit to enhancing it,” Smith says, adding that he has been scheming with Russell about future ventures, including opening a small distillery. “Bob’s done more merchandising, created a real air of openness and communication, and brought a great deal of excitement and exuberance to the area.”

Jenkins says the uniqueness of the mill is a big draw for history buffs and cultural tourists, and that visitors interested in the growing Southern Oregon food and wine scene visit the mill for culinary reasons.

In 2008, the Butte Creek Mill produced more than 250,000 pounds of product, including pancake and cornbread mixes, under the direction of a master miller named Mike Hawkins, who can usually be found in the grinding room with flour smeared on his nose and across his denim button-down shirt. The mill delivers to stores, bakeries, and restaurants throughout Southern Oregon. It also has a small national presence: A retail store in New York City buys Butte Creek products, and gift boxes are shipped around the United States.

After visiting the grinding room most customers head to the mill’s large retail store where the refrigerator case is full of different kinds of Butte Creek flours and things like Wacky Jacky cake mix (to make whole-wheat cake) and Better Beer Bread (a quick bread made with a bottle of beer). The store also sells other local products like Rogue Creamery cheeses, Rising Sun tortas, Oregon jams, and handmade toffees and fudge from Grants Pass.

Despite the mill’s improved visibility and success, Russell felt the pinch of the economy last year. Because of an increased demand for corn-derived ethanol, the drought in Australia and Chinese demand for wheat, the worldwide price of wheat skyrocketed. In 2007, the mill’s standard load of 30,000 pounds of grain cost $2,180, but by the end of 2008 that number had more than quadrupled to $9,710. While this was good for wheat farmers, it has been difficult for consumers, and Russell says he was forced to raise prices and also saw a drop in gift box sales. When one full-time and one part-time employee left, Russell decided not to fill those positions. He currently has five to seven employees, depending on the season.

Still, the business does $500,000 in gross sales, and so far that’s been increasing 10% to 12% every year. Russell says that revenue this year is surprisingly robust and he’s optimistic about the future. But more than the money, owning this mill is a labor of love for Bob Russell. It’s perhaps his passion for history and his enthusiasm about telling the mill’s story, more than the entrepreneurial and aesthetic upgrades, which make such a difference at the mill today.

“It’s hard to put a price tag on happiness,” he says. “I have this love for history and antiques and I tell the story of the mill to 10-year-olds and 80-year-olds … and people want to listen.”