How Lumen Learning aims to pry open the multibillion-dollar textbook market.

PORTLAND — In 2013 David Wiley, a 41-year-old father of five, walked away from a successful tenure-track position at Brigham Young University, one of several academic positions he had held for the previous 10 years.

“Not only did I have tenure, I had a retirement plan: a pension plan I was going to be participating in,” he says.

The lure that hooked Wiley was the opportunity to play a pivotal role in the open-educational resources (OER) movement, a rapidly growing international effort to create teaching and learning resources that can be legally adapted and redistributed at low or no cost.

OER can sound to the uninitiated like a free online textbook substitute. But adherents speak of something world historic: a global education movement comprised of academics, college administrators, policymakers and software developers aimed at democratizing knowledge and empowering teachers and students.

Open education is also an emerging industry — the education technology sector’s contribution to the sharing economy — and when Wiley walked away from academic job security, he walked into a startup that hopes to get a piece of a new, multibillion-dollar market.

New business model

That would be Lumen Learning, a Portland-based company Wiley co-founded in 2012 that helps community colleges and four-year universities use open-education materials.

In any democracy movement, there is a monolithic force to be toppled. Among open education supporters, that force — the Goliath to Wiley’s David — is corporate textbook publishers, whom they claim are holding students and faculty hostage to an expensive and unilateral vision of teaching and learning.

“After Comcast, Pearson might be the most disliked company in America,” says Wiley, referring to the world’s largest textbook publisher. “Open education is a way of enabling faculty and students to take back control over the experience, which, somewhere along the way, historically, we allowed publishers to usurp from us.”

Wiley’s co-founder, Lumen CEO Kim Thanos, is more explicit about the business opportunities. “The level of dissatisfaction with the current market is high enough that it needs to be fundamentally redefined,” says Thanos, a former open-source software consultant and ed tech veteran.

“Our goal is to disrupt the industry: to completely restructure the textbook market.”

A resident of Salt Lake City, where he has homeschooled his kids, ages 8 to 19, Wiley is an OER pioneer who has won international recognition for his research. He is also Mormon, an affiliation that is not wholly irrelevant to this story. Thanos, 47, is strategic, market oriented and lives in Portland, where she and her husband are raising three children, ages 13 to 19.

Together the Lumen founders hope to do for education what the solar industry did for sunlight: put a free product in the hands of the people and make a hefty profit in the process.

A movement grows

Fueled by the internet, the open-education movement began to spread in earnest around 15 years ago, when several big players entered the arena. The kickoff was in 2001, when MIT required OpenCourseWare licenses on all of its course materials. (OCWcourses are created at universities and published for free.)

In 2012 the U.S. Department of Labor and Education issued $2 billion in grants to develop open-education materials in community colleges. The Hewlett and Bill & Melinda Gates foundations have funded millions in OER grants. States are also getting onboard. In 2015 Oregon allocated $700,000 to create an OER program that has since awarded grants ranging from $15,000 to $37,000 to nine community colleges and universities.

In a field dominated by government and foundation money, Lumen is one of the first for-profit companies to try to take OER to scale. The company aims to solve a problem: Even though OER materials are widely available — by some counts, there are 1 billion open-education resources in the world — colleges have been slow to incorporate the materials into their classes and degree programs.

“Here it is; it’s free. What’s the problem?” says Cable Green, director of open education at Creative Commons, a nonprofit that has helped fuel the open-education revolution by providing free copyright licenses that give the public permission to share and use educational resources. The answer is that educators outside of OER didn’t know about it. And those who did weren’t sure how to use it. “Colleges needed to train their people, faculty, instructional designers,” Green says. “But community colleges don’t build content; they buy it.”

Education market changes

Back in the day, college textbooks were just that: books students and teachers used as curriculum guides. Today the internet and outcome-based education trends have morphed textbooks into “content.” Teachers don’t stop at buying books; they purchase quizzes, tests, curriculum guides and other education products that support a lucrative assessment and compliance industry, one that is dominated by commercial publishing companies like Pearson (McGraw-Hill and Thomson Reuters are other big players). To compete, open educators must replicate these materials and take on the laborious task of incorporating them into K-12 and higher-education bureaucracies.

Lumen Learning operates in that niche. The company grew out of a Gates Foundation grant — the Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative — Wiley and Thanos received in 2012 to run open general-education courses across eight colleges serving at-risk students. (The pair met at an open education summit in 2009).It was wildly successful, Thanos says. The project cut the cost of required textbooks to zero, and student success rates in some courses increased by over 10% compared to the same courses offered by the same instructors in prior years.

Despite the promising results, the project was far from smooth sailing. At the end of the first semester, Thanos and Wiley gathered together math faculty from one of the colleges, Tompkins Cortland Community College in New York, to debrief. “They were so unhappy with the adoption process that they literally screamed at us, with two of them in tears,” Thanos says. “At that moment, I realized: The train is completely going off the tracks.”

What went wrong? At most community colleges, math faculty use a Pearson product called MyMathLab that not only provides problem sets for students but also auto-grades those items. “When faculty stop using MyMathLab, they have to go back to grading every single math problem,” says Thanos. “Where we saw frustration early on is we didn’t have faculty-support items.”

After the Kaleidoscope experience, Thanos and Wiley decided it was time to regroup. “You start to realize we’ve been through this whole process — all this pain, being screamed at — yet we actually ended that grant happy with impacts on affordability and on student learning,” Wiley says. “You realize if [you] don’t own this work and carry it forward, then those lessons might get lost. It felt like we needed to keep doing it or it wasn’t going to get done.”

That’s when Wiley walked away from tenure, and that’s when he and Thanos founded Lumen. Initial funding came from a subcontract on another Gates Foundation grant and a $250,000 award Wiley received from the Shuttleworth Foundation, a nonprofit in South Africa focused on open-education initiatives.

Eliminating textbook costs

Lumen’s offices are in the Pearl District, where about 27 employees work on product development, back-end technology and sales. The company currently supports courses at more than 100 institutions, and the number of students it serves is doubling every term. From January to June 2016, Lumen served 50,000 students. Thanos says this fall they expect to serve 100,000 students and will likely pass the 200,000 mark in January 2017.

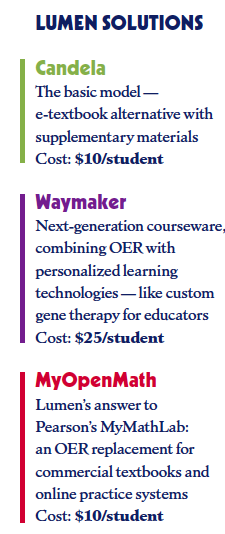

The business model works like this: Lumen provides faculty members and students a package of digital materials comparable to what they would receive from a publisher. It hosts all the materials on a proprietary platform and integrates that platform into a college learning system so students and faculty can access and edit materials.

In return colleges pay Lumen $10 per student per course, a fee that is passed on to students. That’s a 90% to 95% savings over what students would be paying for a regular textbook, Thanos says. It’s a significant chunk of money, especially for low-income students.

Alleviating the burden for at-risk students is a big part of Lumen’s sales pitch to community colleges. First-generation students often don’t realize they have to buy textbooks, Thanos says, and even if they have the money, they often wait a week or two before getting the book, which puts them at an academic disadvantage from the start.

“When I started to understand the obstacles first-generation students faced, that was life changing,” says Thanos, who describes herself as an overprivileged student. (Her father, she says, was in real estate and put his kids to work in a restaurant he bought just so he could teach them a work ethic.)

Not the only solution

Textbook costs are an easy target for open-education reformers. In Oregon, where the state is struggling to meet its ambitious 40-40-20 graduation goals, a 2015 survey conducted by the Higher Education Coordinating Commission found community college students were spending around $250 per term on textbooks — an expense that compromised student success and graduation rates.

But for all the rhetoric about saving money, the cost-savings argument only goes so far. As Ray Henderson, an education technology investor and Lumen board member, points out, there are other ways students can save on textbook costs: Buy used textbooks, for one. “I’m careful,” Henderson says. “I’m not a revolutionary on this. You have to take a little grain of salt when you talk about cost avoidance.”

To sell colleges and students on open education, supporters must lay claim to a broader set of student benefits. Their argument boils down to this: Students who use open-education materials do better in school and have a lower dropout rate than those who don’t.

“OER is not just a textbook, and it’s not simply print-to-digital courseware,” Henderson says. “It’s part of an educational measurement system delivering courseware linked to state standards, compliance and regulation.” The meme today, says Henderson, is “zero-cost degree” — building entire degree programs that use open-education instructional methods. Of the 1,600 community colleges in the U.S., about 20 offer zero-cost degrees; another 20 or 30 are in the works, according to Wiley.

“There’s an epidemiology to it,” he explains. Community colleges tend to locate in clusters, with two to three sited within driving distance of one another. “If you are thinking about majoring in business, and it’s literally 25% cheaper to graduate from this program than that one, then the flow of students puts pressure on the other schools to follow along,” he says.

“There is no reason why the four to five most popular community college degrees shouldn’t be using OER across every single course they offer. In university settings, there is no reason any person should spend money on a textbook their first two years when they are taking general-education requirements.”

The Cerritos Example

In 2010 the student-retention rate in the Cerritos College business department was 67%. “One of the big reasons students didn’t complete is because 80% are on financial aid, and they felt they couldn’t afford it,” says Bob Livingston, the department’s program coordinator.

So in 2012, the department partnered with Lumen and retention rates began to climb — to 73% after a year and 83% today. Now Cerritos, located in Norwalk, Calif., is converting its fundamentals of business and marketing classes to the Waymaker program, with plans to eventually convert the entire business program. Faculty don’t have time to create and update materials, Livingston says. “We’ve created a model that is sustainable and scalable, and I am absolutely thrilled.”

Ivory tower vs the market

Wiley, Lumen’s chief academic officer, is at once mild mannered and intense. Although he left his tenure-track position, he still works at Brigham Young as an adjunct instructor, where he runs an OER research group. An undergraduate music major — Wiley now oversees family jam sessions that include a baby grand piano, a bass and a drum set — he has racked up numerous accolades and awards, including a National Science Foundation CAREER grant and appointments as a nonresident fellow in the Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School.

Depending on what history you read, the OER movement got its start in Utah, says Wiley, who comes to Portland for about a week each month. He points to an alignment between Mormon culture and open education: “Just kind of philosophical, ethical and moral approaches to sharing and service.”

Students aren’t the only beneficiaries of open-education methods, Wiley says. Faculty can edit open-course materials and customize them with their own examples. Administrators also benefit because fewer students drop out of school.

“When you decrease the drop rate, institutions get to hold on to that revenue,” Wiley says. “We’ve shown that students actually take more classes, so that’s new tuition revenue. And if you are in a state where college is funded on a performance basis, then you can unlock performance funding even faster. So it’s goodness all the way around.”

Not everyone is feeling the love. In 2015 Fortune magazine published an article titled “Everybody Hates Pearson,” a lengthy profile that chronicled the challenges facing the global publishing conglomerate. The company’s stock price plummeted this year, and just last month Pearson replaced Don Kilburn, president of the U.S. division. Kilburn continues to work for the company in a business development role.

Pearson is a favorite punching bag for educators, who criticize everything from the company’s aggressive marketing tactics to its efforts to control all aspects of teaching and learning. With OER, Pearson faces a reckoning, Wiley says. “If you’re used to selling students $150 textbooks in a hostage scenario where they have no choice, OER is not a good situation for you,” he says.

Asked to comment, a Pearson spokesperson referred Oregon Business to an in-house op-ed titled, “If OER is the answer, what is the question?” The column acknowledges open education’s cost savings but questions its ability to provide students and faculty with adequate pedagogical materials. It also includes a section describing the emerging for-profit side of open education that seems aimed directly at Lumen.

“There is no free lunch, and most OER proponents understand that,” writes Curtiss Barnes, Pearson’s managing director for global product management and design. “That’s why businesses are beginning to sell services around OER, perhaps in anticipation of the day when the foundation, government and venture capital funding that has kept OER afloat begins to dry up.”

Actually, that’s the same argument Lumen makes, but with a more positive spin. Many academics resist the idea of a for-profit education model, Thanos acknowledges. But OER funding is overly dependent on foundations, she says.

“There needs to be more models funding this work or we’re one economic downturn from it all going away. That was one of the things I learned from the open-source community: that diversity creates a better business model. I didn’t see that in education and saw it as a vulnerability.”

OER’s business-academia divide is reflected at least symbolically in the Thanos-Wiley executive team. “Kim has good intuition for the education side of it, and I’m pretty good at what I do and try not to be an idiot on the business side,” Wiley says. “There’s complete trust. We enjoy poking each other, goading each other. It’s very yin and yang.” He pauses. “Actually, it’s kind of magical.”

Coincidentally, Thanos grew up in Salt Lake City, where she was raised in a Mormon household. A self-described workaholic with an adventurous streak — she and her family take extended trips by sailboat, dropping anchor only to get Wi-Fi — Thanos left the church after high school and is clearly uncomfortable linking OER and the Latter-day Saints. “I generally don’t put BYU in my bio,” says Thanos, who attended Brigham Young’s business school. “It creates assumptions that are incorrect.”

In 2015 Lumen received its first investor funding, from the Portland Seed Fund and the Oregon Angel Fund. “I wanted the company to be located in Portland,” Thanos says. “The community has been very supportive.”

An emerging sector

But so far there’s not much competition. The other big player in the OER support ecosystem is OpenStax, a nonprofit based at Rice University that creates repositories of OER materials. Meanwhile, governments continue to ramp up their investment. Last year the U.S. Department of Education launched #GoOpen, a campaign to encourage states, school districts and educators to use openly licensed educational materials. Just this month, California Governor Jerry Brown allocated $5 million to create zero-textbook-cost degrees at state community colleges.

Oregon’s OER competitive grant program funded several projects including a chemistry series at Western Oregon University, a calculus series at Portland Community College and business classes at the University of Oregon, says Teresa Wolfe, the OER coordinator for the Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Commision. “These are high-enrollment courses students take in community college or the first year of college, a broad range of humanities and science courses,” she says. “They also tend to have very expensive textbooks.”

A former biology professor, Wolfe says a few students every term dropped her classes after hearing about textbook costs. Having course materials on day one, she says, can make or break student success. “There are OER conferences that are international and open-education repositories around the world,” says Wolfe. “It’s a growing movement that isn’t going to slow down anytime soon.”

Lumen aims to be cash positive by 2017, and Thanos says 100% of their sales originate from incoming calls. The startup is the sole technical support provider on a new OER grant led by an organization in Maryland called Achieving the Dream. The company will assist 38 institutions in creating OER-only degree programs. The first courses will go live this fall.

Lumen also received a Next Generation Courseware Challenge grant from the Gates Foundation, a project that marries open-education methods with analysis of a student’s individual learning style.

Disrupting higher education

Customized learning is the latest development in an industry that seems to be a touch point for any number of technology and education trends. Much like Pearson, the traditional college education model is under attack for being overpriced, outdated and underperforming. As the rhetoric around affordability and access for students heats up, Lumen is part of the remaking, grafting a Jeffersonian vision of free education as the bedrock of democracy onto a collaborative-economy market solution.

The long term goal, says Wiley, is a transference of power. “I see faculty and students in total control of the learning experience again: what is said, how it’s said and what examples are used.”

Thanos is less abstract. She circles back to the Tompkins Cortland college math faculty who were so distraught about using open-education materials. Since then, one of the instructors has converted her department to Lumen’s math materials and is now a leader in the Open SUNY Textbook initiative. Tompkins Cortland math students, Thanos says, are saving just over $1.5 million each year in textbook costs.

Imagine scaling that model around the country, she says, “saving $1 billion in textbook costs and putting the money back in hands of students.”

Whatever happened to MOOCs?

The promise of the internet has spawned more than one free education movement. In 2011 MOOCs (massive open online courses) were all the rage. Companies like Coursera and edX and partner universities like Stanford made a big splash with promises to bring Ivy League-quality education to the masses. Then the hype seemed to fade; course completion rates were low, and critics questioned their efficacy and purpose. But behind the scenes, MOOC enrollment has continued to climb. According to data collected by Class Central, the total number of students who signed up for at least one MOOC course has crossed 35 million — up from an estimated 17 million last year.

A version of this article appears in the September issue of Oregon Business.

Correction appended: This article has been amended to reflect the following correction. Don Kilburn was not fired from Pearson. He is no longer president but continues to work for the company in a business development role.