Fred Chown runs one of the oldest family-owned architectural hardware companies in North America. He talked to Oregon Business about the challenges and secrets to staying in business for 137 years.

The TV show Mad Men depicting a culture of drinking and male chauvinism at a New York advertising agency in the 1960s is how Fred Chown describes the business environment his father worked in when he ran the family’s Portland hardware store in the 1950s.

His father, for example, would often have martinis at lunch, says Chown, 66, president of Chown Hardware. In keeping with those heady times, the company would hold “alcohol fest” Christmas office parties. It was a culture that epitomized the freewheeling years of the 1950s and 1960s.

Chown, a bespectacled man sporting a beard and casual short-sleeved shirt and slacks, couldn’t be more different to the depiction of his father. He took over as president of the Portland hardware store in 1986 and now runs a company with annual gross revenues of $27 million and which has been in his family for five generations.

Chown reflected on how his time in business is the complete opposite to his father’s.

“In my dad’s day it was a male dominant Mad Men-type of world. Then my mother changed that culture. My brothers grew up without any prejudices at all, especially not against women because there were a hell of a lot of women at the company that were smarter than we were.”

Though corporate culture changes with each successive generation, there are certain principles of running a business that are as relevant today as they were generations ago.

One piece of advice Chown’s father gave his son before he retired and which he has lived by over the past 30 years is the importance of treating employees as though they are his best customers. It is advice he will also pass onto his oldest son, who will likely take over as president when he retires.

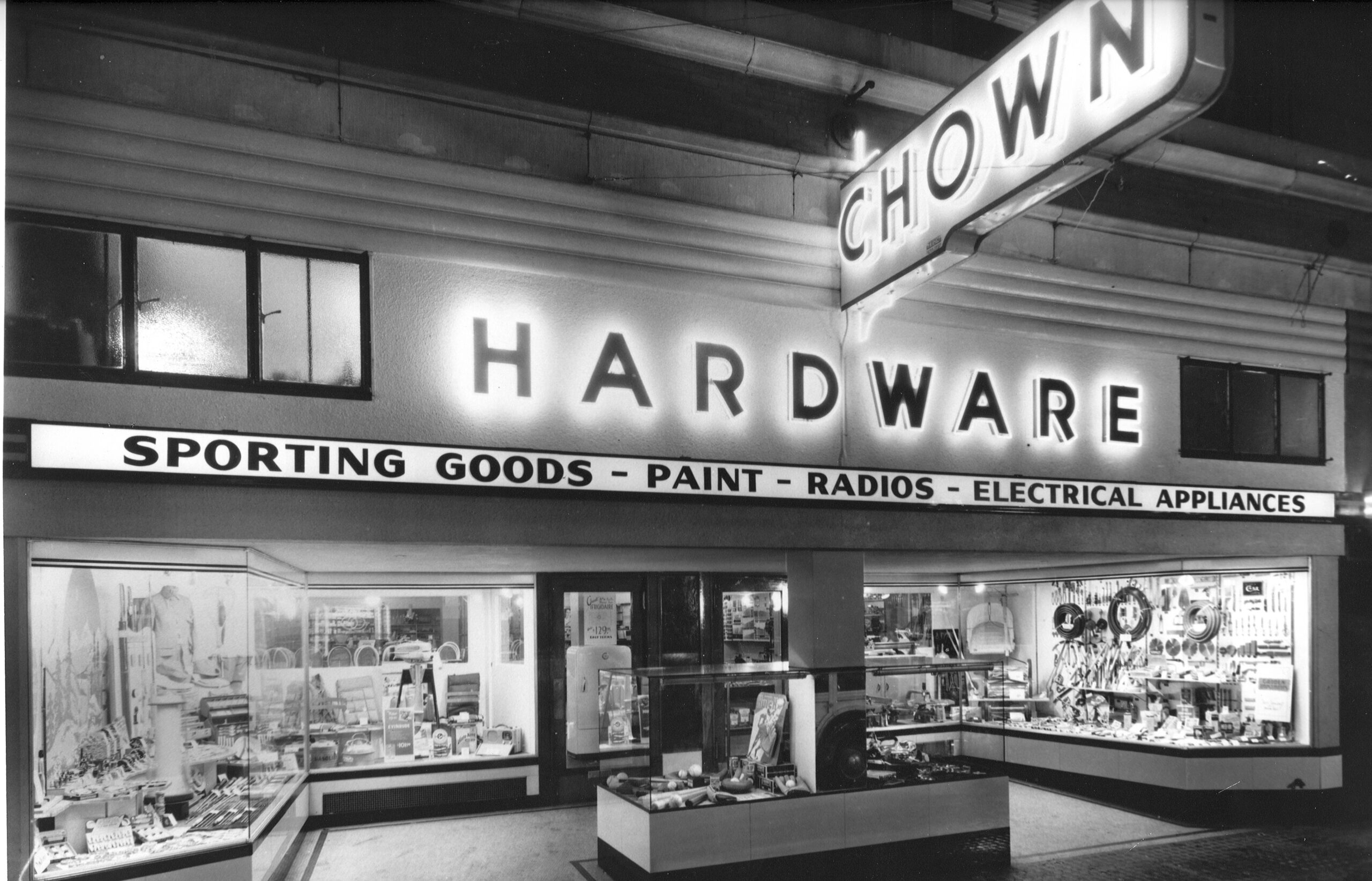

Chown Hardware was started by Fred’s great grandfather, Francis Chown, in September 1879. Francis left Ontario, Canada, where his family owned a hardware store, after a disagreement with his father. He supposedly traveled west with $5,000 in gold and eventually settled in Portland. The store he opened sold logging and farming equipment, reflecting the predominant commerce in the city at the time.  Chown Hardware can be seen here next to Fred Meyer on the left.

Chown Hardware can be seen here next to Fred Meyer on the left.

In those days merchandisers had to buy goods from wholesalers in San Francisco rather than buy directly from the manufacturer. Francis traveled by stagecoach to San Francisco and had inventory shipped to his store in Portland via clipper ships that sailed up the Columbia and Willamette rivers.

Among the more unique items his great grandfather sold were canaries in cages. Rumor has it that the birds were sold to miners; if the canary died it was a sign of harmful gas in the mine and that the miner should get out as soon as he could, hence the term ‘canary in a coal mine.’

Having a long family history can also bring up aspects of the past that would be a liability in the present day. Chown’s great grandfather sold merchandise that today would be considered taboo. For example, his great grandfather sold a calendar depicting racial stereotypes of Chinese people, who came in Oregon in the 1800s to build railroads.

“There are some things in my great grandfather’s history that were racist. I read some old things of my great grandfather’s, which are shocking.”

Chown’s great grandfather handed the business down to his son, Fred’s grandfather, in 1910. Moving with the times, his grandfather sold kitchen appliances, such as refrigerators and washing machines, which had started to become popular. He also sold sporting goods and power tools.

“What was cool about the family business is every generation has had their thing. Whatever your father’s thing or your grandfather’s thing was it didn’t exist anymore. Everyone got to get into what their passion was under the umbrella of a hardware store,” says Chown.

His father Frank took over running the store in the early 1950s after returning from World War II and got into the contract hardware business. The company would submit bids to construction companies to provide hardware, such as locks for buildings.

Chown says his father was a great businessman and cared deeply for his employees, but it was his mother Eleanor who had more business acumen. It was her idea to start a decorative plumbing and hardware business, which the company still operates. His mother opened several stores in Portland, selling high-end plumbing fixtures. Eventually she sold all these shops to concentrate on the main store on NW 16th and Everett.

“It was fun to see her going from mom to businesswoman. We got the backstory that she was probably telling my father what to do all along. He looked smart because my mother was probably the mouthpiece.”

Chown didn’t always want to get into the family business. He dropped out of a law school at Lewis and Clark College in the early 1970s and started building houses on the Oregon Coast with a group of college friends. It was an unsuccessful venture.

“We made no money at all,” says Chown. “I was crazy enough to think I could go out and get a job and market myself as being a builder.”

Fred Chown and his son Kyle.

Fred Chown and his son Kyle.

Chown eventually asked his father for a job and started in 1978 working as the warehouse manager. Then he went on to purchasing manager and sales manager before becoming president. “I ran most of the divisions, which is what got me to be president because I understood what all these jobs were.”

Chown’s own business idea was to get into electronic hardware. A big part of the business is access control, such as selling card readers and fobs, and video surveillance. For the past decade, Chown has also tried to sell hardware directly to customers rather than bidding to sell parts through general contractors.

“The construction industry is still very much low bid oriented. If you are the low bidder you tend to win and you win even if the product is substandard or not to the specification of the client.”

He has faced ups and downs in the economy during his past 30 years at the helm. Competition from larger stores is one hurdle he has had to overcome. The company had to sell the tool business because the big-box stores undercut sales.

The most difficult time for Chown was the most recent recession of 2008-2011. The company had just bought a new building on Front Street in Portland for $4 million when the recession hit. The company was landed with the $30,000 monthly payment. Fortunately Chown was able to find a tenant and just last year sold the building. “That could have been the one thing that could have put us out of business if GE Capital, the original lender, had called the loan. I would have had to liquidate.”

Chown’s eldest son Kyle is the most likely family member to take over as president when Fred retires. His younger son Joel also works at the business, as well as two of his nephews.

An aspiring journalist in college, Kyle worked in restaurants before joining the business in 2009. He currently runs the commercial division. “I knew he was going to be committed because he tattooed one of our logos from the 1990s on his arm,” says Chown.

Chown will turn 79 when the company turns 150. He has no formal succession plan. But he believes it is critical to let his sons make mistakes, be in positions in authority and find their passion for the business.

“It is nice to have something live on when you are no longer here,” he says.