The Archimedes plan for health care reform calls for federal waivers and local control. Will business back it?

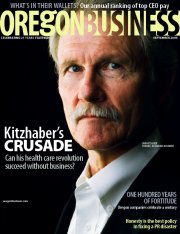

Kitzhaber’s cure

Kitzhaber’s cure

The Archimedes plan for health care reform calls for federal waivers and local control. Will business back it?

By Oakley Brooks

JOHN KITZHABER’S HEALTH REFORM movement has reached a moment of truth.

After Kitzhaber spent the first half of this year rallying for revolution — barnstorming the state and country, raising fists among students and buttoned-up employers, bending the ear of opinion makers, retirees and doctors from La Grande to Ashland and Portland to Philadelphia — it has come to this: By early October, the former governor and emergency room doctor and his grassroots Archimedes Movement must come up with a basic plan for the universal health coverage he has been advocating all year. Then he’ll have to convince some prominent business leaders to back that plan. Kitzhaber wants to put a bill before the Legislature this winter in order to get a new system operating in time to make it a focus of the 2008 presidential election.

But without strong business support — which continues to elude him — his quest for health care reform likely will stall.

“By the end of September, employers will have a chance to look at this and decide if they want to be part of it,” says Kitzhaber, who in August released a first draft of his health bill to Oregon Business (see below). He added candidly, “I’m not really sure how they’re going to react to it.”

THE ARCHIMEDES PLAN

|

Throughout the spring and summer, the business response to Kitzhaber’s ideas has been tepid. His smooth, compelling diagnosis of the current costly health care mess and a plea for some limited, widely available care system has drawn all kinds of people into dialogue. Building on a web-based hub and the expertise of Howard Dean’s campaign guru Joe Trippi, the Archimedes Movement now has 14 chapters from La Grande to Ashland and 2,500 people on its mailing list. Employers large and small have shown up to hear Kitzhaber’s pitch all around the state, and many seem intrigued by his suggestion that something dramatic needs to happen in health care — perhaps even taking some of the burden of health coverage away from the employer. He’s made an effort to link the dysfunctional public health care system with the rise of health care premiums for businesses.

But his diagnosis hasn’t been so moving that the business community, and especially its leaders, is championing his cause. Top CEOs such as Portland General Electric’s Peggy Fowler and Hoffman Construction’s Wayne Drinkward have heard his presentation. But neither they nor any key business leaders outside the health care sector have taken a leadership role in the movement.

Some in the business community attribute this to the fact that, until now, Kitzhaber hasn’t offered any concrete proposal. “He articulates the problem really well, but he’s still working on the solution,” says Duncan Wyse, president of the Oregon Business Council, a Who’s Who of civically active CEOs. Others question whether any overhaul of health care will have enough political support to get through the Legislature. “We’re certainly open to the ideas he’s trying to promote, but from a political standpoint could it be done?” asks Lynn Lundquist, president of the Oregon Business Association and a former speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives. Business groups such as the Oregon Business Council are also working on their own reform efforts at the same time as Kitzhaber. Fowler and Drinkward are part of an OBC health task force that is focusing on market-based reform aimed at controlling costs in the current employer-based health insurance arena.

This fall, Kitzhaber can count on organized labor and some health insurers and hospital executives to help him shape his new health care system. But having a wide range of employers involved is crucial because they are today the single biggest group of health care purchasers in the state (see chart, below left) and stand to be affected most by an overhaul of the current system. They also faced a 9% increase in health insurance premiums last year. In short, they are in a position to exert a lot of influence on health care and they’re searching for change.

Estimated total health care expenditures in Oregon in 2004  The above estimate was made by health care consultant Bill Kramer for the state Office of Health Policy and Research, using state and national data. The above estimate was made by health care consultant Bill Kramer for the state Office of Health Policy and Research, using state and national data. |

“I’m convinced that employers could make this happen,” Kitzhaber says. “If you could get employers and employees together you could fix this.”

Kitzhaber has also seen business work against him on health care. He served two terms as governor between 1995 and 2003, but he’s probably best known for engineering the Oregon Health Plan, aimed at broadening the group of low-income people with health coverage in the state, when he was Senate president in the late 1980s and early ’90s. Initially, business groups such as Associated Oregon Industries supported the health plan and a companion bill mandating that employers offer health insurance to their workers. But then business support fell apart, and the mandate never made it into law and Kitzhaber blames that, in part, for the erosion of the health care picture in Oregon. There are currently more than 600,000 people without health insurance in the state, as both businesses and the Oregon Health Plan have been dropping people off health rolls due to higher costs.

This time around, the 59-year-old Kitzhaber will also be asking businesses to back a monumental change: He wants the tax credits they currently receive for health care spending to be diverted to fund basic, universal health services.

FOR MOST OF THIS YEAR, that’s about as detailed as Kitzhaber would get on his plan to overhaul health care. His speeches focused on the dysfunction of the current system and proposed that Oregon more effectively use the estimated $6 billion-$10 billion of public money used for health care — the federal tax credits given to businesses and the combined budgets in Oregon for Medicaid and Medicare, the health programs for low-income residents and seniors.

But in August, Kitzhaber outlined more specifically how his bill might look. Not surprisingly, it’s very similar to the Oregon Health Plan legislation, which asked the federal government to let Oregon spend expanded Medicaid dollars as it saw fit. The new draft proposes that the federal government grant waivers to Oregon to decide how to spend public health dollars and that the state use a body like the Oregon Health Policy Commission (which oversees the Oregon Health Plan) to decide what to do with the money.

The draft bill also lays out 12 principles to guide that decision-making body — such as “equality” and “effectiveness” — but also practical items such as malpractice reform and health information technology. Kitzhaber says this will provide the “sideboards” for a new basic system. And they are the part of the bill he hopes to hammer out with interest groups, including employers, in the next several weeks.

Increases in health insurance premiums, 1988-2005  Source: KFF/HRET Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, 1999-2005; KPMG Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, 1993, 1996; The Health Insurance Association of America (HIAA), 1988, 1990. Source: KFF/HRET Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, 1999-2005; KPMG Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, 1993, 1996; The Health Insurance Association of America (HIAA), 1988, 1990. |

He had hoped to have this draft in hand several months earlier, written with help of a small group of employers, seniors, hospital execs and other stakeholders. But that group, to be called the Archimedes Council, hasn’t come together as planned, like several other elements of the movement, including a late-arriving website, a confusing name (Archimedes was a Greek mathematician and philosopher) and an erratic series of events. Kitzhaber rallied a jam-packed Portland State University event room in February and then hit a two-month lull before a “launch” and interactive meeting in April. “It’s been kinda like changing a tire while you’re going down the highway at 50 miles per hour,” Kitzhaber says with a cheeky grin.

He insists that he now has some big-name businessmen on board — traditional supporters of his including Brooks Resources chairman Mike Hollern and Greenbrier CEO Bill Furman — and they’ll help him get the plan a fair airing this fall.

WILL OREGON EMPLOYERS BUY INTO SUCH A PLAN? In May, Kitzhaber had an opportunity to gauge opinion in an employer-only group — 100 human resource reps and executives gathered at a sprawling, rainbow-colored conference space in Springfield’s Royal Caribbean Cruise Line headquarters. Some of the attendees were members of a local group looking to expand access to health care in the area. Other employers seemed new to the scene and wore blank expressions, as if they wondered exactly what it was they’d signed up for.

Jeff Elliot, president of JCI, a local manufacturer of rock crushers, was nursing a coffee at the edge of the group milling around before Kitzhaber started. “I’m here to see what’s happening,” he said. Elliot’s company competes against Asian manufacturers and he said health care costs were holding him back considerably in that race. “We’re putting more money toward health care than we’re sending to the federal government in taxes,” Elliot said.

Soon after, Kitzhaber started his speech, where he detailed a system that “nobody could support if it were written into law.” To him, Medicare and Medicaid are at the heart of health care’s spiraling costs and swelling numbers of uninsured. Over-65s are the single richest segment of the population and a fast-growing one at that, but they are guaranteed health care, which will mean a $65 trillion liability over the next several decades that payroll taxes on workers and employers can’t support. Meanwhile, as low-income people continue to be purged from the rolls of Medicaid and business health care plans, their recourse is the emergency room, by law an all-comers venue but the most expensive and inefficient place to treat people.

Kitzhaber estimates that treatment for those who can’t pay, in the ER and elsewhere, accounts for 10% of private insurance premiums. That means as the number of people heading to the ER grows, so do insurance premiums.

Kitzhaber argues that the billions spent on health care in Oregon each year need to be used in a more intentional way that benefits a broad group of people. His model is the public education system. There, nobody sends kids home from school when the budget gets tight (or at least they make the funny pages when they do). Instead, you raise the class size or limit extracurricular offerings. In health care, this means paring down covered services to what’s necessary so as many people as possible can access it.

Kitzhaber finished his “rant” with a wink and a smile, and the crowd broke into small groups where they rattled off a litany of health-care-related issues that are becoming alarmingly familiar in business circles: pay increases held down, staff stress up, loss of employees to companies with better plans, possible layoffs.

When it came time for solutions, one group said they liked the idea of a universal program, as widespread “as car insurance.” Mike Warner, HR director at Marathon Coach in Coburg, suggested that if government provided a basic level of public care for everyone, businesses might buy add-ons for their employees. How to pay for it? “Scratch-it tickets,” Warner said. Then, a little more seriously, he added, “How about a health care program so good that employers would move here and the new tax revenue would pay for it? We’ve been chasing jobs away for so long and this would be a good incentive for them.”

Kitzhaber finished the session by taking a short list of suggestions from the crowd. One woman scrolled through her list before landing on, “The system is so broken that you can’t tweak it to fix it.” Kitzhaber smiled broadly and raised a fist like Nelson Mandela.

WHILE KITZHABER’S MOVEMENT HAS BEEN GROWING, members of the Oregon Business Council have been working on their own fixes for health care’s woes. They are centered on equipping individuals and businesses to be more intelligent purchasers of health care and health plans. Eventually, with hospitals and health systems cooperating to provide intelligible information, consumers would be able to size up health care services the way they would a cup of coffee or a stereo system.

As it stands now, the real costs and quality information are hidden from the consumers. Meanwhile, the cost of procedures and wasted money in the system grows unabated. “They are no normal economic checks that create an economically sustainable system,” says Mark Ganz, CEO of The Regence Group and a member of the OBC’s health task force. Ganz and the OBC say that all other fixes to health care, including expanding access to health insurance, are secondary to infusing the scene with market forces. “If we don’t get at that, we’ll never have a sustainable model. That’s the problem with the Massachusetts plan,” he says, referring to a new law there containing a web of incentives and penalties for businesses and individuals, and subsidies for the poor aimed at achieving universal coverage. “It never addressed that.”

That casts Kitzhaber’s plan as a sort of limited solution for business interests.

Even so, both Kitzhaber and OBC members stress that their two prescriptions can coexist.

“I don’t think that anybody has the one solution, but I gravitate back to my consumer and employer base when I look at this,” says Hoffman’s Wayne Drinkward, who heard Kitzhaber’s presentation this winter and says he hasn’t ruled out supporting Archimedes in the future.

Ganz suggests there isn’t any friction between the two approaches. “We’re coming at this from two different directions, but I think they’re mostly complementary.”

Oregonians eligible for the Oregon Health Plan by category, 1994 – 2006  All values are for February of the year indicated. All values are for February of the year indicated.Oregonians without health insurance,1990 – 2004  Source: Office for Oregon Health Policy and Research Source: Office for Oregon Health Policy and ResearchRISING HEALTH CARE COSTS have led both businesses and the state of Oregon to drop people from their health plans. The number of uninsured people in Oregon has grown by more than 200,000 since 2000, to well over 600,000. As the state has had to narrow the low-income population that qualifies for the Oregon Health Plan, the number of people living in poverty in the state has grown — leading to a growth of the lowest- income members of the plan. |

Kitzhaber doesn’t argue with the approach of groups such as the OBC, which may also present policy recommendations to the Legislature this winter. He hasn’t suggested scrapping the various private sector reforms, such as the move from employers paying workers’ monthly insurance premiums to providing them with a pot of money in health savings accounts, which are designed to make employees more judicious in their health care spending. Nor has he advocated the quick fix of universal coverage. On his Archimedes blog in April, he also cited the shortcomings of the new Massachusetts health plan. Of his own plan, he says, “If we haven’t managed costs, we haven’t accomplished anything.”

In Kitzhaber’s view, however, there are certain medical procedures that should be widely available and not left up to the private insurance market. The public should decide what those procedures are and fund them with public dollars.

“I don’t think this will replace employer-based health coverage,” Kitzhaber says. “But insurance is a hedge against catastrophe. So why would you insure against immunizations or routine checks for hypertension or diabetes? You want that. That’s a public good. And almost every other industrialized nation has come to that conclusion.”

The Archimedes staff has begun talking with local public relations firms to package that pitch. And Ganz says they will need a strong sell to get the business community to buy into the loss of tax credits — in essence, higher taxes — to pay for those basic health benefits.

“If it was part of a comprehensive fix, I would say great, if that’s what it takes to fundamentally change it,” Ganz says. “But if it is just taken away in isolation, employers will say ‘Wait a minute, I want to provide health care to my employees.’”

But Drinkward thinks the two groups will work out a two-pronged solution, regardless of what happens to the tax credit. (He says bigger businesses like his will provide health care regardless of whether it’s tax deductible.)

Drinkward says there’s an urgency to health care costs and care that’s similar to the workers’ compensation system crisis in the mid-1980s, when costs were climbing through the roof and then-Gov. Neil Goldschmidt convened a labor-management meeting in 1990 at Mahonia Hall, the governor’s mansion. The two sides rewrote the state workers’ comp laws and put costs in check.

“There we had a policy solution but we also made our worksites safer,” Drinkward says. “I look at health care the same way. There’s some policy stuff that will help. But we can also make people healthier and take control of how we engage the system.”

WHATEVER BECOMES OF THE ARCHIMEDES MOVEMENT plan in Salem this winter, John Kitzhaber has figured out what the business community has not — how to turn the words “health care” from a conversation killer into a lively dialogue.

His governorship flamed out in an obstinate moment in 2002, when he infamously proclaimed the state “ungovernable” during a bitter fight with legislators who wouldn’t accept his tax increase proposals. But after hinting at another run for governor this winter, he now uses his disconnection from political office as an invitation to conversation and a rallying cry for change — for the moment, change in health care.

“Tom McCall had to live with the line ‘Come visit but don’t stay.’ Mine is ‘Oregon is ungovernable,’ but I still believe that,” he says. “The capacity of our legislative institutions to respond to these complex problems is really limited. Everything is so partisan and transactional. You can’t fix health care that way. You have to engage people in a discussion about the values and the trade-offs and the choices and drive that back into the political system.”

Kitzhaber’s 30-minute speech, “On the Road to Revolution: Fear and Loathing in the U.S. Health Care System,” which he’s given dozens of times since he left office in 2003, has now evolved into a mini-Inconvenient Truth: an unwinding of one of the gnarliest, most pressing but politically untouchable problems. (Kitzhaber has been employed during this extended road show by two foundations, The Foundation for Medical Excellence in Portland and the hospital-quality-focused Estes Park Institute in Colorado.)

After hearing one delivery of the speech at a health forum in Portland this spring, Sen. Betsy Johnson, a Democrat from Scappoose, turned to her neighbor and gasped, “God, he’s good.” Then Bruce Goldberg, director of Oregon’s Department of Human Services and the morning’s moderator, said through the microphone, “Governor, sign me up.” Peter Kohler, Oregon Health & Science University’s outgoing chief, was scheduled to speak next. “I feel like a pair of brown shoes at a black tie dinner,” Kohler grumbled wryly into the microphone.

Several anecdotes bring Kitzhaber’s speech to life — an aging salmon swimming up the Rogue River, a seizure victim whose lack of cheap prescription drugs eventually cost the state $1 million — but one that he rarely uses might be the most important. Last year, Kitzhaber watched his 88-year-old mother die. (His father also passed away in June.) Near the end, it looked like she might have an intestinal tumor, and she decided not to have all the procedures to determine what exactly was going on. But the attending physician prescribed regular blood tests anyway to keep tabs on her. That’s when Kitzhaber met him square on: No more tests. “She went home and the quality of her life improved rapidly,” he says. “My dad and she had been living around the laboratory waiting for the next results. All of the sudden they let go of what they couldn’t control — that they were mortal — and embraced what they could control — a 65-year marriage.”

As Kitzhaber notes, Medicare would have paid for hospital stays and blood workups, whatever the cost. But it wouldn’t pay for a home nurse. He had long advocated for a sensible use of public dollars, but the dysfunction of the system had never been so clear. “That’s when I realized we’ve got to stop defending these programs and ask ourselves what we’re really getting.”

A few months later, he announced in front of a phalanx of TV cameras that he would give up another run at the governor’s office and return to work on that in which he began — finding the right medicine for something seriously ailing.

On the Web:

Archimedes Movement

www.oregonbusiness.com/leadership/

Join the discussion about leadership. Send feedback to [email protected].