BY JENNIFER MARGULIS

As schools implement more rigorous academic standards, holistic and flexible approaches to K-12 education flourish.

BY JENNIFER MARGULIS | ART BY LEIF NOBLE

BY JENNIFER MARGULIS | ART BY LEIF NOBLE

Beginning this school year, all K-12 public school students will be evaluated by the Common Core state standards, a set of rigorous academic standards created by several outside groups including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and adopted by states around the country.

But even as Oregon pursues a familiar course of standardized testing, another education trend is also emerging — one that focuses on investing in the whole child, and ensuring all children have not just the academic but also the social and emotional resources to enter the workforce and become productive members of society and the economy.

It’s a yin-and-yang approach that characterizes modern-day education reform, theory and practice. Common Core will help create consistent results and accountability in Oregon schools, says Duncan Wyse, president of the Oregon Business Council. But the whole-child approach is equally serious business, aimed at addressing the overwhelming social and economic problems facing many Oregon students, as well as the sociocultural demands of a constantly shifting global economy.

Common Core testing begins next spring. In the meantime, Oregon Business decided to spotlight a few people working on the holistic and flexible side. Dr. Nancy Golden, chief education officer for the Oregon Education Investment Board, talks about closing the “opportunity gap” facing disadvantaged kids. The president of Concordia University and principal of Faubion K-8 discuss their pioneering “3 to Ph.D.” partnership. We also check in with an Ashland tech executive — a cloudtechnology pioneer who explains why he enrolled his son in a Waldorf school that eschews technology in the classroom.

It’s a diverse, loosely connected set of voices that highlights the complexity of the educational landscape and the variety of innovations springing up alongside a uniform academic standard.

Closing the opportunity gap

| Dr. Nancy Golden Chief Education Officer Oregon Education Investment Board |

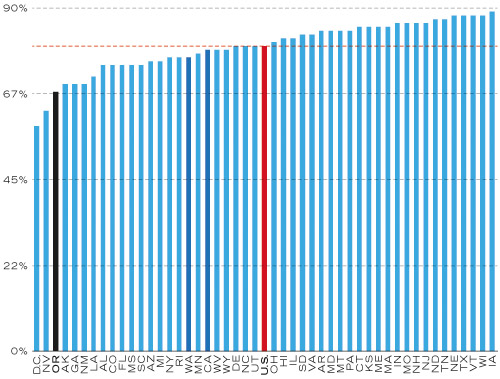

Ask Dr. Nancy Golden what challenges Oregon’s K-12 education system faces today and she has some unsettling statistics to share. Originally from New York, articulate and fast talking, Golden, chief education officer for the Oregon Education Investment Board, points out that nearly one in four children in Oregon is living in poverty. The graduation rate in Oregon’s high schools is only 68.5% (which is third to last in the nation and substantially lower than the national average of 78.2%, according to the U.S. Department of Education), and for students of color, it is less than 60%.

“We have a lot of kids who haven’t had advantages and are without the same skill set as others,” explains Golden, who worked as the superintendent of the Springfield public schools for over a decade. “That does not mean that kids aren’t smart; it just means they haven’t had the same opportunities. These kids are coming to school hungry, they may never have been read to, they have no place to sleep. They have some basic needs that need to be attended to for them to learn and close the opportunity gap.”

Kids with challenges at home. Rising rates of autism, allergies and other special needs among children in Oregon. A large and often disenfranchised immigrant population (some 378,000 immigrants live in Oregon, according to the American Immigration Council), which includes the children of itinerant migrant workers. Teachers who see their class size increasing and their own energy and enthusiasm decreasing apace. Shrinking state and local budgets. There are pages of statistics detailing the problems in Oregon’s K-12 educational system.

Though she readily admits that her solutions are mostly to effect change at the policy level, Golden has some on-the-ground suggestions about how to improve the schools, and she is especially interested in improving the lives (and test scores) of Oregon children who are at an opportunity disadvantage.

| U.S. GRADUATION RATE BY STATE: 2011-12 |

|

As Oregon’s demographics change, a trend Golden considers an asset to the state, Golden believes educators are going to have to adapt. “We can’t teach the way we used to anymore. We’re not a one-size-fits-all, because we are not a one-size-fits-all state.” Her solution is a big-picture idea: Look at and help cultivate all aspects of the child’s growth. It’s not just about imparting information; it’s about “changing the way we do schools,” says Golden. That means connecting at-risk kids with culturally specific organizations, community organizations and health care organizations to help them move into a position where they are ready to learn.

“We’re going to see more integration between economic development, health care and education than you’ve ever seen before,” Golden says. She says the David Douglas School District, one of the most diverse and challenging in Portland, has found that having preschools and health clinics inside the K-12 schools themselves helps prepare young children for kindergarten readiness and keep kids in school.

Golden also wants schools to respond to the equally important needs of accelerated learners, who are an important resource with no funding designated to meet their needs, and who can be turned off by stultifying boredom. “It’s important to put kids at their right rate of learning so it will always be challenging.” For that reason, the state has adopted a flexible approach to implementing academic standards, Golden says. She calls it “the tight-loose” system. “We are using the Common Core ,but we are loose on how it is implemented. The schools get to decide.”

Golden has put this sort of flexibility into practice during her own tenure as superintendent of the Springfield schools, where she saw good results with project-based instruction that allows kids to move at their own pace. When Khan Academy, an online education program in math and science, was used by teachers in the classroom, students who were more advanced could move quickly to self-directed projects and experiments, while students who needed more help could spend class time with the teacher for clarification.

Golden also points to the Academy of Arts and Academics (nicknamed “A3”) in Springfield as a visionary charter school that really responds to students’ needs by implementing a similar kind of project-based learning. The results have been impressive, if mathdefying: For the second year in a row, A3 has graduated more students than began as freshmen.

It isn’t just about the special needs of the disadvantaged or the academically accelerated, but matching the individuals across the spectrum of needs. “We are all in this together; it’s the collective impact,” Golden says. If kids don’t have food, then you have to say: ‘What’s the nonprofit in your area that can help kids get food?’” Collaboration between education and business integrating college and career is also essential. “This is a major part of our work: to make connections between organizations.”

From 3 to Ph.D

| LaShawn Lee Principal, Faubion School |

| Charles Schlimpert President, Concordia University |

When LaShawn Lee first took the helm as principal of Faubion School on Rosa Parks Way in Portland, she knew she had a hard task at hand. The school was deemed “failing” by the district, which was converting it from a K-5 school to a K-8; more students were transferring out than transferring in; some kids lived as far as a 90-minute bus ride away; 20% of the students were homeless; and extreme poverty was making it hard for students to learn. But Lee is a woman who likes challenges. She’s also no stranger to poverty-stricken schools, having taught in the poorest parts of the Carolinas for 20 years.

Lee had been in the building for less than an hour and a half when a representative from Concordia University’s Department of Education stopped by to welcome her. Concordia, walking distance from Faubion, is a Lutheran university with a mission to serve. Lee says her Southern hospitality kicked in and she asked her colleague to sit down. They talked for three hours about Faubion’s immediate needs (art classes) and macro plans for the next five to 10 years.

That fateful conversation was the beginning of a mutually beneficial partnership that started with Concordia education majors coming to Faubion to teach art, and that will culminate in a new School of Education building integrated into Faubion’s building site that will open in fall 2017.

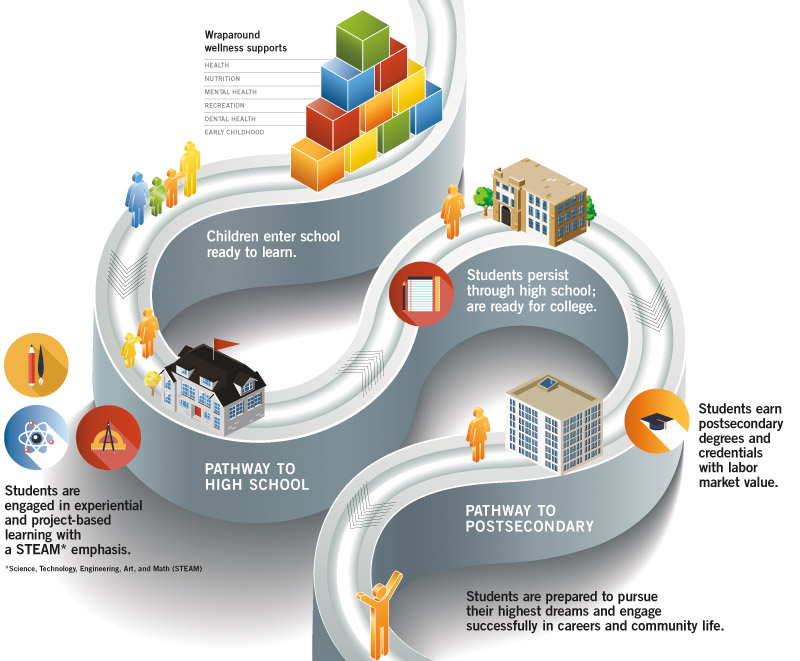

According to Concordia University president Charles Schlimpert, who has been instrumental in making this partnership successful, Concordia-Faubion’s relationship is part of a bigger plan at Concordia to help Oregon’s young adults realize their dreams. They call this project, “3 to Ph.D.” The three refers to the first three trimesters of life; the idea being that children need a good foundation, starting in utero, in order to thrive. Concordia’s vision is not necessarily for every child in Oregon to earn a Ph.D. but rather to encourage lifelong learning and inspire students to reach their highest educational goals.

The Concordia-Faubion private-public partnership represents a huge financial investment for the university — Schlimpert says, all told, it will cost them about $15 million — but he believes the experience his students are getting and the financial and social benefits to the community make the investment more than worthwhile.

Indeed, since Concordia and Faubion teamed up, there have been tangible and practically overnight results. One of the biggest problems Lee faced as a principal was the lack of supervision on the playground. Seventy percent of her discipline referrals came from playground brawls, she says. This was something Concordia students from the athletic department could fix. “They taught the kids 400 playground games,” Lee explains. “Now everyone follows the rules. My discipline referrals went from 70% to zero! We haven’t had a single one in the last five years.”

Indeed, since Concordia and Faubion teamed up, there have been tangible and practically overnight results. One of the biggest problems Lee faced as a principal was the lack of supervision on the playground. Seventy percent of her discipline referrals came from playground brawls, she says. This was something Concordia students from the athletic department could fix. “They taught the kids 400 playground games,” Lee explains. “Now everyone follows the rules. My discipline referrals went from 70% to zero! We haven’t had a single one in the last five years.”

Concordia students are on the playground and they are also in the classrooms. Instead of a 30-to-1 student-to -teacher ratio, the school now has a 6-to -1 ratio. Students are no longer leaving for other schools; instead, they are begging to come to Faubion. “You can find four adults in a classroom with our students: teachers, practicum students from Concordia, student teachers who come for 15 weeks and Concordia volunteers doing service-learning hours,” Lee explains. Pre-K children visit Concordia’s library one day a week. They eagerly look forward to it, clamoring to the teacher, “Is it the day I go to college? Is it my college day?”

Concordia students are on the playground and they are also in the classrooms. Instead of a 30-to-1 student-to -teacher ratio, the school now has a 6-to -1 ratio. Students are no longer leaving for other schools; instead, they are begging to come to Faubion. “You can find four adults in a classroom with our students: teachers, practicum students from Concordia, student teachers who come for 15 weeks and Concordia volunteers doing service-learning hours,” Lee explains. Pre-K children visit Concordia’s library one day a week. They eagerly look forward to it, clamoring to the teacher, “Is it the day I go to college? Is it my college day?”

The benefits to the university students, 40% of whom are the first in their family to go to college, are also palpable. They are becoming more culturally sensitive, getting real-life classroom experience, and having the chance to find viable solutions to the educational problems faced by Oregon children who are trying to thrive despite the opportunity gap.

“It is a great thing for the Concordia students,” says Madeline Turnock, advisor to the president. “They come to a real-life situation with real-life people. You can’t get that from sitting in a classroom and reading a case study.”

Key to the partnership is the good relationship and good communication between public and private sectors, Schlimpert and Lee say. “It’s about listening first,” Lee says. That’s the difference. Concordia did not come in with an agenda. They asked, ‘What can we do for you? What do you need? And how can we help?’ They’ve never overstepped their boundaries.”

3 TO PHD: THE VISION

Fostering EQ

Allan Adler

Channel Cloud Consulting

Stephen Sendar

Founder, Siskiyou School

Allan Adler, 54, runs a completely remote organization. As someone who helped develop the cloud and as founder of Channel Cloud Consulting, a management consulting firm that advises companies around the world on how to sell and market their products more effectively, Adler spends his work life on the computer. “We help companies like SAP [a European multinational software corporation] figure out how to transform their businesses in light of these changes in order to help their customers,” he explains.

So you would think this 54-year-old entrepreneur would want the same for his children, right?

But he doesn’t. Adler’s oldest son, who will begin at Ashland High School in the fall, and his daughter, who is going into fifth grade, have both attended Waldorf education their whole lives. Waldorf schools, which follow the teachings of Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, are places where computers are not used in elementary instruction; television watching and video games at home are actively discouraged; and technology like Smart Boards with access to Edmodo, Skype, ePals and Wikipedia generally play no part in the pedagogy.

But he doesn’t. Adler’s oldest son, who will begin at Ashland High School in the fall, and his daughter, who is going into fifth grade, have both attended Waldorf education their whole lives. Waldorf schools, which follow the teachings of Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, are places where computers are not used in elementary instruction; television watching and video games at home are actively discouraged; and technology like Smart Boards with access to Edmodo, Skype, ePals and Wikipedia generally play no part in the pedagogy.

Why would a technologically minded parent like Adler want such a nontech education for his children? Because he thinks his children are being better educated without it. “There are two kinds of intelligence: book and IQ,” Adler explains, “and emotional intelligence, called EQ. You can have all the IQ you want, but if your EQ’s not high, you are not going to have a good life. I was confident my kids would get the intellectual education anywhere they went, but I wasn’t sure where they would get the emotional.”

Adler thinks the best way to ensure that his children are successful in the world is to help them with emotional maturity and interpersonal skills. He moved his family from Arizona specifically so his children could attend the Siskiyou School in Ashland. “Waldorf is all about educating the child inside out,” he says. “You don’t learn things just with your head; you have to have your head and heart involved. It’s an enormously different approach.”

Instead of test-taking and typing skills, the Siskiyou School, like other Waldorf schools, includes handwork (knitting is taught in first grade, crocheting in third, cross-stitch in fourth), music, art, outdoor time and movement-based learning (children memorize the countries and capitals in Africa while jumping rope, and learn math using rhythm sticks). “It’s not just about shut-up-and-do-the-work, and memorizing stuff,” Adler says.

Computers are not introduced into the classroom until middle school at the earliest. As much as he values the Siskiyou School’s approach, Adler admits that making such a countercultural educational choice isn’t always easy. “Part of me says there is value in exposing children to things early,” he says. “The other side of me says, ‘Are you kidding? Do you really think kids are going to fall behind because they don’t use technology in school? That’s insane.’”

Stephen Sendar, a founder of the Siskiyou School, past president of the Board of Directors, and himself a Waldorf parent, believes that limiting access to technology in the classroom is one of the reasons the children at the Siskiyou School thrive. “There are two really important reasons not to use technology at all in the classroom in the early years. One is for the happiness of your child; children find deep joy and learning in imaginative play, and being unconnected allows them to be free to explore and integrate their activities with all of their senses,” Sendar says.

“The second is that the time for using technology effectively is later in life, after a foundation for creativity and open-ended thinking is built; then your child can use the technology in service of her mental and emotional faculties to enhance the generation and implementation of original ideas.” For Oregon’s software businesses, the take-home is clear: Kids need the creativity necessary for software design early, and the actual coding skills later.

The school does not keep statistics, but the high school graduation rate from students who attend the K-8 Siskiyou School hovers around 100%.

Tight and loose

Though it seems radically different, the Siskiyou School approach dovetails with what Dr. Nancy Golden, LaShawn Lee, Charles Schlimpert and others are trying to do: address all of the needs of the child, not just the academic ones. Add to that the new Common Core standards and Oregon schools, public and private, seem to be moving toward a system that is at once rigid and flexible, rational and creative, standardized and custom. Is this a contradiction in terms? Not at all, says Golden. A multifaceted approach to learning is in sync with the needs of the state’s diverse student population and the fluid nature of a rapidly shifting international marketplace, she says.

“My educational philosophy is whatever works for students is what matters.”