A data scientist crunches the numbers.

A data scientist crunches the numbers.

BY LINDA BAKER

|

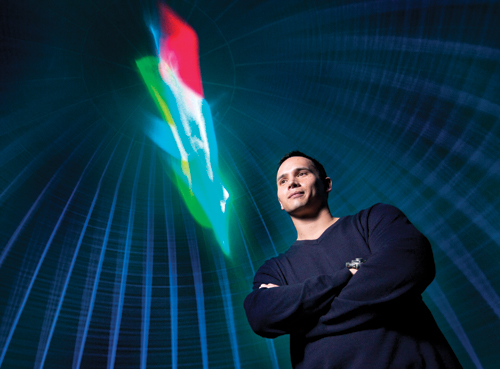

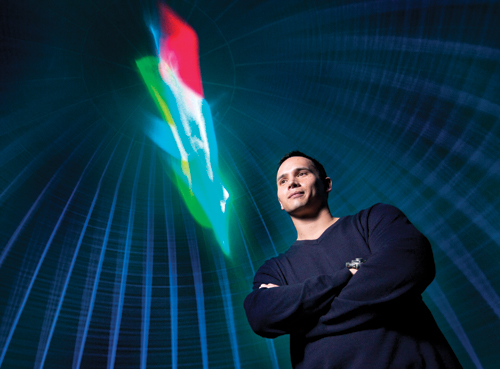

Thomas Thurston exploring laser mathematics at OMSI’s Kendall Planetarium// Photo by Adam Wickham |

Thomas Thurston is in his office above Lela’s Bistro in Northwest Portland, describing an entrepreneur he talked to earlier that week. “It just bugged me. Something about this person — every time I engaged with him, it just bugged me.” The CEO of Growth Science, Thurston doesn’t usually traffic in gut feelings. On the contrary, the 35-year-old “data scientist” is strictly in the numbers game, creating computer algorithms to predict whether new companies and innovations will succeed or fail.

Until recently, Thurston worked primarily as a consultant to large Fortune 500 companies. But this past January, Growth Science shifted its focus to smaller companies and startups, deploying a model with a reported accuracy rate of 85%. “It’s not perfect, but we’re predicting way better than intuition,” says Thurston of his (top secret) formula, which combines elements of statistics, computer science and cutting-edge business strategy theory.

In February Thurston signed on as a partner at the San Francisco-based Ironstone Group venture fund, bringing his method for identifying winners and losers to an industry that often bases decisions on personal relationships and those ineffable gut feelings. “People who start companies are brave, smart, likable,” says Thurston. “But if we don’t get a green light with the model, we’re not going to invest.”

Mild-mannered and self-deprecating — “Gosh, I’m not an engineer, I’ve never taken calculus; my value is asking the stupid questions” — Thurston holds law and MBA degrees and worked as an attorney for several years before moving to Intel Capital, a venture capital group that invests in outside companies. While reviewing potential investment candidates, Thurston became interested in looking for patterns that might indicate which businesses would go boom or bust.

So he pored over Intel case studies, business school innovation theories and obscure German doctoral theses, eventually creating a model based on Harvard Business School guru Clayton Christensen’s theory of “disruptive innovation”: the process by which a product or service enters at the bottom of the market, then gathers momentum and eventually surpasses established competitors.

How does Thurston’s model work? It’s rooted in the mountains of data he has collected on market and corporate dynamics, including the anticipation of future changes in the marketplace. Patterns of success or failure then emerge depending on different industry and business behaviors. “The key is identifying variables that are predictive of success and failure,” says Thurston, who is very hush-hush about those variables. It’s a process that involves “lots of hard, hard work,” he says. “You go through a whole haystack to find one needle.”

Since founding Growth Science five years ago, Thurston, a University of Oregon graduate who lives in Lake Oswego, has worked on automating the model to make it affordable for entrepreneurs, as well as for the billion-dollar companies that have been using the company’s simulations to guide product launches and acquisitions. The son of U.S. government aid workers who grew up in Honduras, Bolivia and Nepal, Thurston describes his work as “a social mission.” About 80% of startups fail, he laments. “People are losing their jobs; it’s terrible.”

Aiming to make more businesses fail less, Growth Science not only runs the simulation, but if the model gives a thumbs-down, it also offers guidance as to how to yield a better success rate.

Extracting meaning and benefits from the reams of data unleashed by the information age has become all the rage in the past few years. Or, as Thurston puts it, data science is “taking off like a hockey puck.” Numerical models are being deployed to predict how the Supreme Court will rule on a given case, to find cures for disease, even to predict where crimes will happen. Data science entered the popular vernacular last year, when statistician Nate Silver plugged in information culled from polls, demographics, party registration and other sources — and correctly forecast the results of the 2012 presidential election in all 50 states.

Using computer simulations to predict the outcome of business decisions makes a lot of managers, executives and entrepreneurs uneasy, admits Thurston. “They’re afraid if the algorithm does the work, that brings their value and job into question.” Not to worry, he says, emphasizing that data science is simply about pattern recognition: “the tacit admission there are patterns in business — and that there are some patterns human brains are lousy at recognizing.”

But there will always be room for the human factor. An algorithm, observes Thurston, can’t tell if someone is annoying — like that hapless entrepreneur — or if a given product is interesting. “A computer,” he says, “can’t look at something and say it’s awesome.”