Oregon is dominated by small daily and weekly papers. While they haven’t dodged the recession’s wrath, in today’s declining newspaper market smaller is turning out to be better.

THE SMALL-TOWN NEWS

THE SMALL-TOWN NEWS

Oregon is dominated by small daily and weekly papers. While they haven’t dodged the recession’s wrath, in today’s declining newspaper market smaller is turning out to be better.

BY MICHELLE V. RAFTER

Mike Olson cannot imagine Forest Grove without the News-Times, the city’s weekly newspaper. He’s read it since moving to town as a boy 50 years ago. As a small- business owner and former president of the city’s chamber of commerce, he believes a newspaper plays an important role in a small town. Take it away, Olson says, and a town loses its identity. “It would be a little more of Main Street disappearing,” he says.

But in the 13 years since Olson opened Olson’s Bicycles, he’s never advertised in the paper, relying instead on word of mouth and putting what little money he has for marketing into his website.

That in a nutshell sums up the dilemma facing Oregon’s small daily and weekly newspapers — how to remain relevant in the local community while the economy and the newspaper business are collapsing.

It is a problem facing newspapers across the country, and not just the small ones. The double whammy of the recession and declining advertising and circulation as more people get their news online is crippling the industry. Ad revenue at U.S. newspapers dropped 18% in the third quarter of 2008 alone, according to the Newspaper Association of America. Readership has plummeted too, dropping 18.1% between 1990 and 2007.

It is a problem facing newspapers across the country, and not just the small ones. The double whammy of the recession and declining advertising and circulation as more people get their news online is crippling the industry. Ad revenue at U.S. newspapers dropped 18% in the third quarter of 2008 alone, according to the Newspaper Association of America. Readership has plummeted too, dropping 18.1% between 1990 and 2007.

Not a pretty picture, but not one that necessarily spells doom for the community dailies and weeklies like the News-Times. According to publishers, analysts and other industry watchers, they are best positioned to weather both the current economic slump and changes in the newspaper business.

Oregon is a land of community newspapers. Of the Oregon Newspaper Publishers Association’s approximately 88 members, only the Oregonian ranks among the nation’s top 100, with daily circulation of about 283,000. The rest are dailies and weeklies with circulation in the thousands or tens of thousands.

It’s not that small newspapers have totally dodged the effects of the recession. Across the country, owners are downsizing, selling or folding community papers in attempts to deal with falling revenue. Small papers were more optimistic about the industry in 2008, but going into 2009 are just as pessimistic as their larger counterparts, according to an annual industry poll conducted by Kubas Consultants, a Toronto media industry analyst.

But small papers are better off than the major metro dailies, says Ed Strapagiel, Kubas’ executive vice president, a sentiment that’s echoed by local newspaper publishers in the state. For one, small papers aren’t as dependent on classifieds and national advertising as bigger dailies, according to Strapagiel. Small papers are also more likely to already be operating on lower profit margins, have a monopoly on news in their community, are privately or family run, and because of their small size, can be quicker to embrace opportunity, he says. Put them together and all of those factors are helping buffer small papers from the current trends ravaging the major dailies.

“In many cases the local paper is the only local news source and is loyal to the community,” Strapagiel says. “It’s why those papers haven’t seen the big drop in circulation that the major dailies have suffered from the intrusion of the Internet, and other competitors hungry for advertising dollars. For newspapers in a small town, there’s still a sense that it’s their paper.”

You could say that in today’s newspaper business, smaller really is better.

Small papers that are in the best shape financially have figured out new ways of doing business, diversifying their revenue base and embracing the Internet, according to industry analysts.

One of the state’s more forward-thinking publishers is East Oregonian Publishing Co., the fourth-generation family business that owns the East Oregonian in Pendleton, a six-day 8,700-circulation paper; the Daily Astorian, a five-day, 7,400-circulation paper; and the Capital Press, a Salem-based 36,500- circulation farm weekly. The Salem-based company also runs weeklies in Enterprise, Hermiston, John Day, Manzanita, Cannon Beach and Long Beach, Wash., as well as real estate guides and supplements.

East Oregonian CEO Steve Forrester has long relied on outside experts for guidance, including advisers from Oregon State University’s Austin Family Business Program. Forrester adopted the same tactic when developing the company’s Internet strategy, tapping Lucy Mohl — a digital media veteran who worked at Seattle-based Real Networks, the Seattle Times, and now Microsoft — as a board member from 2002 to 2007.

Based on that guidance, the company diversified geographically, acquiring or starting small weeklies close to its larger dailies to take advantage of existing presses and economies of scale. The company also expanded its product mix, launching a contract printing business and book publishing division. It also started websites for all its papers plus two others: the Seaside-Sun.com, an online-only news site, and a farmland real-estate marketplace covering 36 states called FarmSeller.com.

Diversification is paying off. East Oregonian’s combined newspaper circulation of 68,000 has held steady, as has its 205-person workforce. The privately held company doesn’t disclose finances. But company officials say the newspaper division posted double-digit profits in the first six months of the fiscal year that started July 1, 2008, despite classified advertising sales that started softening near the end of that period due to the recession. In the previous fiscal year, ended June 30, 2008, they report profits were almost equally divided between commercial printing (28%), newspapers (27%), ancillary operations (26%) and Internet properties (19%). COO John Perry is especially pleased with the company’s Internet business, “since five years ago we lost 2% on that business.”

Business is so good, over the next few years East Oregonian plans to spend an undisclosed amount — “from $2 million to $8 million,” according to Forrester — to replace a 40-year-old press at the Daily Astorian and construct a new building to house it. Forrester says it will be the company’s single-largest capital investment in 95 years.

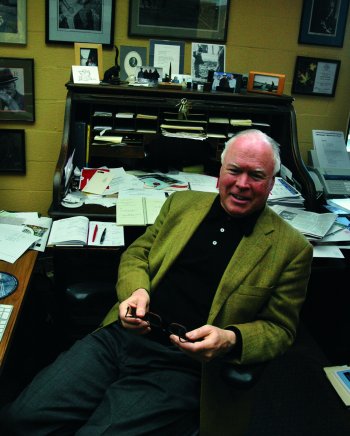

Steve Forrester, CEO of the East Oregonian Publishing Co., which publishes the Daily Astorian and several other small papers. PHOTO BY DAVID PLECHL |

Oregon’s small papers also benefit from private ownership. Only three publicly traded newspaper companies operate in Oregon. Gannett publishes the 46,800-circulation Statesman Journal in Salem and smaller papers in Stayton and Silverton. Ottaway, British media magnate Rupert Murdoch’s community paper group, runs papers in Medford and Ashland. Lee Enterprises, the Iowa chain that owns papers in Corvallis, Albany and Coos Bay, has seen the most trouble. In January, Lee notified securities regulators that it might have trouble paying debts over the next two years, causing the company’s outside auditors to issue a “going concern” alert questioning its ability to remain in business. Lee shuttered the Springfield News in October 2006 after failing to find a buyer for the money-losing paper. Spokesman Dan Hayes says the chain’s other Pacific Northwest papers are in no danger of closing.

In contrast, the state’s community papers that are family businesses or privately held are shielded from needing to show constant quarterly earnings increases or the need to answer to Wall Street analysts and shareholders.

The Klamath Falls Herald and News, a 15,000-circulation daily, has had a hard year, but thanks to private owners, is positioned to ride out bad times. In late December, declining ad revenue and the expectation of higher newsprint costs forced the paper to drop its Monday edition and trim its page size. Publisher Heidi Wright made the changes after ruling out advertising or subscription rate increases and opting not to trim staff more than she already had in an August layoff that eliminated about 17% of the paper’s full-time employees.

The economy in the Klamath Basin doesn’t look like it’ll be better next year, so changes had to happen, but the paper is in no danger of shutting down, Wright says. Pioneer Newspapers, the paper’s Seattle-based, family-run owner, paid $14 million cash for a new building and presses for the Herald and News in 2007, and unlike some much larger public chains, has no debt, Wright says. “That’s one of the things that will keep us strong in the future,” she says.

When it comes to advertising, small papers never carried the same level of classifieds and ads from national advertisers that bigger papers had. So when classifieds started moving to Craigslist and elsewhere online and display advertisers cut back due to the economy, it didn’t impact them as much as it did the metro dailies, says Tim Gleason, dean of the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication.

Sue Peterson, general manager at the Burns Times-Herald, a 3,500-circulation weekly, saw the writing on the wall for national advertising years ago and gradually removed it from her annual ad budget forecast. Today the paper, which serves Burns and Hines in southeastern Oregon’s remote Harney County, relies solely on local merchants for its ad base — and is doing well because of it. “I’m over what revenue I budgeted for the year by $7,000 to $10,000,” Peterson says. “If you were to look at my little world, you’d never know anything’s wrong in the big one.”

Doing well is relative. Hard times are par for the course in Harney County — Oregon’s largest and one of its poorest counties — so the Times-Herald has always operated lean and mean. The paper gets by with seven full-time employees plus five contract paper carriers.

The Times-Herald staff took a big step in controlling their own destiny in 2006. After the paper changed hands three times in two years, Peterson and four other employees bought out the then-owner for $400,000 with a $100,000 down payment scraped together from second mortgages, savings and a $34,000 state grant. “He was a yuppie skier type and we’re so rural,” Peterson says. “To keep the paper the way the community liked it, it was necessary. And we have a very close family group here. We didn’t want anyone to lose their job.”

In small towns such as Burns, another saving grace of community papers is their lock on local news. Most small towns don’t have TV or radio stations covering local events. “We give people something they can’t get anywhere else,” says John Schrag, a former news editor at Willamette Week, the Portland alternative weekly, who became editor and publisher at the Forest Grove News-Times five years ago. “If you want to know how the Banks Braves girls’ basketball team did, there’s really only one outlet in the universe that can tell you, our printed paper or our website.”

The News-Times is part of Pamplin Media Group’s 20-year-old Community Newspapers chain of 11 suburban weeklies and six monthlies in Multnomah, Washington, Clackamas and Columbia counties. The News-Times has received several state newspaper awards for general excellence during Schrag’s tenure, and subscriptions were up between 5% and 7% in 2008. But Schrag is the first to admit that editorially the paper isn’t as good as it has been because of the cutbacks he was forced to make after the area’s building boom died and real estate developers pulled their ads.

So far, local merchants — such as bike shop owner Mike Olson — haven’t picked up the slack. Although Schrag hasn’t laid off anyone, he hasn’t filled jobs when people left. “We’re as good a newspaper as we can be. But there’s no way to do more with less,” Schrag says. “I don’t like it, but it’s the best we can do right now.”

Papers in areas such as Central Oregon that were hit hard by the real estate downturn are some of the worst off. “It’s as bleak as anything in the last 30 years,” says Gary Husman, publisher of the Redmond Spokesman. The 5,000-circulation weekly is owned by Western Communications, a family-run chain with papers in Bend, Baker City, Brookings and La Grande, plus a Central Oregon nickel ads circular.

Husman hasn’t fired any of his 10-person staff, but if someone left he wouldn’t fill the job. The paper cut expenses by sharing a photographer and reporter with the bigger Bend Bulletin and delaying plans to start a website. To keep ad revenue coming in, sales reps — and Husman — are calling on prospects beyond the paper’s normal geographic boundaries. “It’s not rocket science,” Husman says. “We knock on more doors.”

The troubles plaguing major newspaper publishers have depressed small papers’ market valuations and made it harder for prospective buyers to get loans. According to Tom Mauldin, the Sisters-based Pacific Northwest representative of newspaper broker W. B. Grimes, a few years ago owners of small papers looking to sell out could get seven to 12 times cash flow. Today it’s more like five to eight times. While there’s no shortage of would-be buyers, credit’s all but dried up due to the financial crisis. Lenders who previously wanted 20% down now want 35%, and charge 12% or 13% interest on the balance. Consequently, there aren’t a lot of transactions taking place, Mauldin says.

Still, Mauldin and other industry watchers predict sales of small papers will pick up once federal bailout money trickles into the auto industry, the real estate market rebounds and consumers start spending again, though nobody’s saying exactly when that will happen. When it does, buyers will be there. “People who invest in community papers can make a good living and do a tremendous service for their community,” Mauldin says.

The definition of community is changing and it’s affecting the newspaper business, but it’s changing less radically in small towns and local papers continue to benefit from that, says Gleason, UO’s journalism school dean. “If you live in a small town in Oregon, you still identify with that small town and that influences readership and relevance.”

Portland journalist Michelle V. Rafter covers business for local and national publications.

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]